Outline

Certified Backyard Wildilfe Habitat

Management Strategies to Reduce Damage

Animals Commonly Encountered in Gardens, Lawns, and Landscapes

Objectives

This chapter teaches people to:

- Create a wildlife habitat in their own landscape.

- Identify the positive and negative aspects of wildlife in home landscapes.

- Identify common wildlife pests, game, non-game and migratory birds and techniques to prevent and minimize damage.

- Understand the conservation laws that regulate wildlife in urban and suburban areas.

Introduction

Wildlife can bring endless enjoyment to a gardener. Many gardeners find no greater pleasure than relaxing outdoors watching hummingbirds sip nectar from trumpet flowers (Bignonia capreolata) (Figure 20–1) or bumble bees busying themselves on an aster vine (Ampelaster carolinianus). With development increasing across North Carolina and the loss of open lands, many wild species have adapted to survive in close proximity to humans. Yards are their new habitat, and wildlife visits bring opportunities for animal sightings that may not have been possible otherwise. There is more land in backyards than all the national parks combined (Emrath, 2006). Individual backyards are islands that can be connected within neighborhoods and cities to provide viable habitat for frogs, bats, birds, bees, lizards, salamanders, moths, migratory birds, and butterflies. There are many easy, inexpensive ways to make a yard a wildlife sanctuary.

Figure 20–1. A hummingbird sipping nectar from a trumpet flower.

Kelly Colgan Azar, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0

Planning a Wildlife Habitat

Creating an effective wildlife habitat requires a thoughtful plan. Trees and shrubs are more difficult to rearrange in a yard than are furniture or artwork in a home. Careful evaluation of the desired use of the yard and how it can better support wildlife results in a beautiful, functional landscape that increases the property value and the owner’s enjoyment.

Journaling

The first step in any big project is observing the current situation. Keep a log or notebook and record any wildlife sightings in the yard. Be sure to indicate the number of individuals, time of day, season, weather, and any plants or structures used by wildlife. As a gardener moves through a project, the log book becomes an excellent tool to see how changing the landscape affects the number and variety of wildlife seen. Keeping good records also helps in expanding the habitat. Making a note that a nesting pair of cardinals used a maple tree last spring might inspire you to select another maple when you decide to plant another tree. See Appendix A for more on garden journaling.

Please refer to “Landscape Design,” chapter 19, for a step-by-step guide to creating an inviting outdoor space. A basic plan that meets human needs can also incorporate elements that support wildlife. Wildlife require four major resources to be successful: cover, food, water, and a place to raise young. Including each of these four elements in the landscape increases the presence of wildlife.

Wildlife require four major resources: food, cover, water, and a place to raise young.

Plan for Year-round Food

The best way to meet the food requirements of wildlife is to include a wide variety of plants. To encourage greater wildlife diversity, extend food availability by selecting plants that bloom and fruit at different times of the year. Plants provide food through their leaves, flowers, nectar, fruits, seeds, and nuts. Plants that are native to North Carolina are the best choices for North Carolina wildlife. Native plants offer the food and cover sources to which native wildlife have adapted over many years. Also, using native plants reduces the likelihood of introducing exotic invasive species. Invasive species out-compete native plants and may leave wildlife with no food source. In addition to selecting plants to provide food for wildlife, it is important to manage the plants to maximize their output. Unmown grass provides seeds for many species of birds and small mammals. Consider insects, worms, and spiders as food for wildlife and leave them alone. It may be necessary to protect young plants until they are established and can become a sustainable food source for wildlife. In the meantime, begin attracting wildlife by providing feeders.

Black oil sunflower seeds, thistle seeds, and millet are recommended for songbirds. Black oil sunflower seeds are preferred because they have more nut meat and less hull than the black and white striped sunflower seeds and they attract a wider variety of birds. Follow these steps to keep bird feeders clean and free of mold and disease.

- Once a week, rake up waste food, husks, and other accumulated material below feeders on the ground and add it to compost.

- Consider providing multiple feeders, spaced apart in the landscape.

- Use feeders that do not have sharp points or edges. Bacteria and viruses on contaminated surfaces can infect healthy birds through even small scratches.

- Clean and disinfect feeders at least once every two weeks, and more often if sick birds appear. Allow the feeder to air dry before refilling.

- Do not dispense food that smells musty, feels wet, looks moldy, or has fungus growing on it.

Feeding Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds are attracted to bright colors, so select a feeder that has red parts (Figure 20–2). Yellow, however, attracts insects, so avoid feeders that have yellow. Fill the feeder with a mixture of 4 cups water to 1 cup sugar (4:1 ratio). Do NOT use honey. Do not use red food coloring in the solution. Red feeders are enough to attract the birds. Feeders can be left up year-round but should be cleaned weekly with a toothbrush and mild detergent to prevent the spread of bacteria or disease organisms to hummingbirds visiting the feeder. Most hummingbirds leave North Carolina in mid-October and return in late March.

Cover

Wildlife need adequate cover from predators and protection from the elements. Cover allows animals to use less energy as it protects them from cold winter winds or rain and shades them in the summer. Also, cover provides a place to build a nest or den or just to sleep or rest. Providing several layers in your landscape through the use of ground covers, shrubs, and low and high canopy trees can assure a variety of places for wildlife to hide. Rock outcroppings are another cover option. Consider leaving piles of brush in corners of your yard as they are excellent cover for birds and small mammals. Snags, or dead trees, make excellent places for animals to find food and cover (Figure 20–3).

Water

Although many wildlife species obtain all the water they need from their food, a clean drink of water is always welcome. Despite North Carolina’s rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds, a water source may not be nearby. In that case, consider adding one to increase the chances of wildlife sightings. A man-made pond can provide a beautiful centerpiece to your landscape and water for wildlife. Ponds should slope to allow animals to drink without the risk of drowning. Birdbaths are another and less expensive option. They can be purchased from a garden center or created using any shallow container, such as a garbage can lid or a terracotta saucer. Birdbaths should be shallow, no more than 3 inches deep, and should have nonslippery sides and bottoms (Figure 20–4). Stones and sticks can be placed in the birdbath to give birds and butterflies places to perch while they take a drink or bathe. Placing a birdbath under a tree provides cover against predators and a place birds can fly to after they bathe to preen their feathers. Water should be kept fresh and changed every few days to avoid the hatching of mosquito larvae and spreading of disease organisms. Clean the bath with a bristle brush and dish detergent once every week. Every two weeks after cleaning the bath, sanitize it by filling it with a solution of one part bleach to ten parts water solution and letting it stand for 3 minutes. Then empty the bath down the sink and rinse well.

Place to Raise Young

Building birdhouses or leaving a snag helps cavity-nesting birds. Prevent invasive bird species such as starlings or house sparrows from outcompeting native songbirds for nesting boxes by ensuring the entry holes are too small for these non-native birds and by removing all perches from birdhouses. Be sure to include a metal plate around the opening so that squirrels cannot make the opening wider for themselves. For proper nest box construction measurements, check with a local Cooperative Extension office or visit nestwatch.org.

The resource list at the end of this chapter includes publications and Internet sources with additional ways to attract wildlife.

Certified Backyard Wildlife Habitat

After providing the necessary resources for wildlife in the backyard and following the principles and guidelines outlined in previous chapters for maintaining soil, air, and water quality, a gardener can register with the National Wildlife Federation to become a “Certified Backyard Wildlife Habitat” (Figure 20–5). Be sure to share new knowledge and encourage neighbors to provide increased habitat. Multiple connected yards with good resources are much more effective at sustaining wildlife than a single lot. The gardener is a habitat manager and through collaboration with neighbors can profoundly benefit the wildlife that share neighborhood living spaces. If neighborhood residents are on board, they can register their neighborhood and become certified by the National Wildlife Federation.

Ways to Attract Nocturnal Animals to the Garden

There is nothing quite like sitting on the porch at dusk watching bats perform aerial acrobatics while snatching mosquitos out of the sky, or listening to male frogs serenade their potential mates with a cacophony of croaks. Like their daytime counterparts, nocturnal animals have these basic requirements: food, water, and places to rest and raise young. Here are some tips to help attract species large and small:

1. Grow the nectar plants that night-shift pollinators prefer. Good candidates for moths include native night bloomers such as evening primroses, yuccas, and phlox (Figure 20–6). To attract giant silk moths, grow the host plants of their caterpillars, such as oak, sassafras, maple, birch, ash, willow, and cherry. Think of the caterpillars as baby silk moths and recognize they must eat leaves to grow. Tolerate some damage now to enjoy the magnificent adults later.

2. Avoid pesticides, which can harm insect pollinators and amphibians.

3. Offer a drink. Like many other animals, bats everywhere are drawn to garden ponds and other water features.

4. Supplement nature’s offerings with man-made habitat elements. Buy or build a bat house (plans are available at Bat Conservation International). Or construct a nest box for owls (see the website of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology for proper dimensions).

Do Not Make These Common Mistakes

- Plant flowers for the adult butterflies, but no plants to feed the baby butterflies (caterpillars).

- Plant flowers to attract adult butterflies, and then spray the caterpillars (baby butterflies) that hatch from the eggs laid by the adults.

- Spray for pests and accidentally kill honey bees. If you must use pesticides, never spray blooming plants and spray only in late afternoon when bees are done foraging for the day.

Figure 20–2. A hummingbird feeder. Red parts will attract the birds. There is no need to dye the sugar syrup red.

Francesco Veronesi, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 20–3. A snag was left in this landscape providing cover for many birds and beneficial insects. Water, another essential component to a wildlife habitat, is also seen here.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Figure 20–6. Plants that bloom at night or have pale colors can attract nocturnal pollinators like bats or moths.

SyGrnwd, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Injured Wildlife

A gardener may encounter injured wildlife. Knowing the steps to take helps make this time less stressful for the humans and the animals.

No Help Needed

Leave these animals undisturbed. They are able to care for themselves, or their mother is probably hiding nearby:

- White-tailed deer fawns

- Fledgling (young bird, fully feathered)

- Rabbit whose body is at least 4 inches long

- Opossum whose body (not including tail) is at least 9 inches long

- Squirrel who is nearly full size

Might Need Help?

- Brought in by a cat or a dog

- Injured (bleeding, broken limb, concussion)

- Covered in insects

- Nearly featherless bird

- Shivering or cold to the touch

- Parents are dead

How to help

- Put children and pets inside to protect them and the wildlife.

- Note exactly where and when the animal was found so it can be returned.

- Baby birds or squirrels—put featherless chicks and baby squirrels back in their nests. If the nest is too high, or not visible, create a temporary nest using a small plastic container with holes in the bottom. Fill with pine straw, grass, or leaves and attach to a tree near where the baby was found. Place the baby in the nest and watch from a distance to see if the parents return. If they do not return within two hours, place the baby in a small covered box with air holes and transport it to a nearby certified wildlife rescue organization or Wildlife Rehabilitator. DO NOT give it food or water. The hole at the back of their tongues leads directly into their trachea and they can be drowned accidentally. It is illegal to possess or raise wild birds without state and federal permits.

- Bird stunned after flying into glass—protect it from predators, if after a few minutes it has not revived on its own, place the bird on several paper towels in a small box with small holes in the top for ventilation. Tie the box closed and place in a dark, quiet room. In 20 minutes, or sooner if the bird stirs, take the box outside, point it toward an open area, and release the bird. If the injury occurs within 1⁄2-hour before sunset, keep the bird in the box until morning. DO NOT provide food or water.

- In North Carolina rabies occurs most often in raccoons, bats, foxes, and skunks. DO NOT handle these animals.

- Injured and diseased animals may be more aggressive; be extremely cautious.

- For more information and to identify a Wildlife Rehabilitator in your county, contact the NC Wildlife Resources Commission—Injured/Orphaned Wildlife.

Wildlife Interactions

The adage “if you build it they will come” is certainly true for wildlife habitats. Providing food, cover, water, and a place to raise young attracts many desirable wildlife species as well as some unexpected wildlife. When wildlife help themselves to carefully tended gardens or ornamental plants or dig tunnels through pristine lawns, they can frustrate a homeowner. Forethought and careful management can prevent these species from becoming pests. Gardeners must be tolerant and balance the fact that we reside in former wildlife homes with the desire to maintain a beautiful yard and garden.

Preventing wildlife damage is much easier than dealing with established problems, but not all conflicts can be prevented. Here are some simple integrated pest management (IPM) techniques that can help prevent and manage common wildlife-related issues.

- Assess the damage. Determine how much damage to tolerate before intervening. Sighting a single pest does not always mean control is needed.

- Identify and monitor pests. Most organisms are innocuous, and many are beneficial. Properly identifying wildlife and closely monitoring the pest and the damage helps lead to appropriate control decisions. Not all pests require control.

- Prevention is a first line of defense. IPM programs work to manage the landscape to prevent pests from becoming a threat to plants or structures. Prevention can be cost-effective, conserve time, and present little to no risk to people or the environment. Here are some prevention techniques:

- Secure or remove food sources such as pet food or birdseed. Feed pets indoors.

- Remove any brush or wood piles near buildings.

- Block off decks, porches, and roof and basement access points with wire netting or a combination of steel wool and spray foam.

- Seal garbage cans.

- Create barriers around prized plants or beds with fencing or bird netting for cover.

- Scare tactics can be used temporarily to keep animals out of the yard. Flash tape, noise makers, scary eyes, or scarecrows are most effective when they are moved to a new location every few days. Motion lights can startle when they first come on, but eventually, the animal gets used to the light. Flashing or strobe lights work best. A motion sensor on a garden hose that sprays when an animal triggers the sensor can be very effective. Although scare tactics may be temporarily effective, little scientific evidence exists on their long-term effectiveness.

- Manage effectively. Preventative methods and scare tactics are often effective at addressing wildlife problems, however, when those options fail, legal lethal techniques can be implemented to address the ongoing damage. All wildlife have protections under the law, so be sure to consult the resources in this guide and/or the state Wildlife Resources Commission for guidance on legal lethal methods that can be used for a given species. Certified Wildlife Damage Control Agents can also be hired to assess and carry out legal lethal and non-lethal damage management. You can find a list of these agents online.

- Evaluate the strategy. If further monitoring indicates the chosen strategy is not working, then additional pest control methods can be employed.

Intentionally attracting one type of wildlife can also unintentionally attract undesired wildlife. For example, birdseed put out to attract songbirds can fall on the ground below bird feeders and attract mice. Damage caused by wildlife can be costly and discouraging to gardeners. Unfortunately, there are no single, quick, or guaranteed solutions to most animal pest problems. The information below focuses on the most common wildlife problems, the relevant laws and regulations, and suggested management strategies.

Legal Requirements

Virtually all species of wildlife are protected at some level and are regulated by state and/or federal laws and regulations. Local ordinances, such as those regarding the discharge of firearms, may apply to wildlife management. The legal requirements under both federal and state laws apply, and compliance with one does not negate the requirements of the other.

Table 20–1. Mammals that may visit a yard.

| Common Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|

| Armadillo, Nine-banded | Dasypus novemcinctus |

| Beaver, North American | Castor canadensis |

| Coyote | Canis latrans |

| Deer, White-tailed | Odocoileus virginianus |

| Fox, Gray | Urocyon cinereoargenteus |

| Fox, Red | Vulpes vulpes |

| Groundhog | Marmota monax |

| Mink, American | Mustela vison |

| Mole, eastern | Scalopus aquaticus |

| Mole, hairy-tailed | Parascalops breweri |

| Mole, star-nosed | Condylura cristata |

| Muskrat | Ondatra zibethicus |

| Nutria; Coypu | Myocastor coypus |

| Raccoon | Procyon lotor |

| Skunk | Mephitis mephitis |

| Squirrel, Carolina northern flying | Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus |

| Squirrel, Eastern gray | Sciurus carolinensis |

| Squirrel, Fox | Sciurus niger |

| Squirrel, Southern flying | Glaucomys volans |

| Vole, pine | Microtus pinetorum |

| Vole, meadow | Microtus pennsylvanicus |

State Regulations

When wildlife causes substantial damage to a landowner's or lessee's property, he/she can apply for a permit from the NC Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC) to remove individuals of the species involved. Permit requests or questions about state laws and regulations should be addressed to the NCWRC (see box below). No depredation permits can be authorized for the taking of wildlife on someone else's property.

NCWRC

Centennial Campus

1751 Varsity Drive

Raleigh, NC 27606

866-318-2401

The permit can be used only by the landowner, lessee, or someone named on the permit by the landowner/lessee when the necessary control cannot be obtained without capturing or killing the animal(s). The permit must specify whether the animal(s) will be killed or trapped and may place certain restrictions to limit the taking to the intended purpose. Trapping animals for depredation comes under statewide trapping law, G.S.113-291.6.

Table 20–2. Birds that may visit a yard.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Common Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| URBAN ADAPTERS | |||

| European starling | Sturnus vulgaris | Rock pigeon | Columba livia |

| House sparrow | Passer domesticus | ||

| SUBURBAN ADAPTERS | |||

| House Finch | Haemorhous mexicanus | Red-bellied woodpecker | Melanerpes carolinus |

| Northern mockingbird | Mimus polyglottos | White-breasted nuthatch | Sitta carolinensis |

| Mourning dove | Zenaida macroura | Northern flicker | Colaptes auratus |

| American robin | Turdus migratorius | Eastern phoebe | Sayornis phoebe |

| American crow | Corvus brachyrhynchos | Gray catbird | Dumetella carolinensis |

| Common grackle | Quiscalus quiscula | Eastern towhee | Pipilo erythrophthalmus |

| Brown-headed cowbird | Molothrus ater | Eastern bluebird | Sialia sialis |

| Blue jay | Cyanocitta cristata | Chipping sparrow | Spizella passerina |

| Carolina chickadee | Poecile carolinensis | Song sparrow | Melospiza melodia |

| Tufted titmouse | Baeolophus bicolor | Brown-headed nuthatch | Sitta pusilla |

| Chimney swift | Chaetura pelagica | Purple martin | Progne subis |

| Northern cardinal | Cardinalis cardinalis | Ruby-throated hummingbird | Archilochus colubris |

| Carolina wren | Thryothorus ludovicianus | Red-winged blackbird | Agelaius phoeniceus |

| Brown thrasher | Toxostoma rufum | Hairy woodpecker | Picoides villosus |

| Pine warbler | Setophaga pinus | Eastern screech owl | Megascops asio |

| American goldfinch | Spinus tristis | Common nighthawk | Chordeiles minor |

| Downy woodpecker | Picoides pubescens | Red-shouldered hawk | Buteo lineatus |

| URBAN/SUBURBAN AVOIDERS | |||

| Field sparrow | Spizella pusilla | Red-cockaded woodpecker | Picoides borealis |

| Red-headed woodpecker | Melanerpes erythrocephalus | Acadian flycatcher | Empidonax virescens |

| Great crested flycatcher | Myiarchus crinitus | Yellow-throated vireo | Vireo flavifrons |

| Wood thrush | Hylocichla mustelina | Yellow-billed cuckoo | Coccyzus americanus |

| Red-eyed vireo | Vireo olivaceus | American redstart | Setophaga ruticilla |

| Killdeer | Charadrius vociferus | Yellow warbler | Setophaga petechia |

| Orchard oriole | Icterus spurius | Hooded warbler | Setophaga citrina |

| Summer tanager | Piranga rubra | Louisiana waterthrush | Parkesia motacilla |

| Blue-gray gnatcatcher | Polioptila caerulea | Blue grosbeak | Passerina caerulea |

| Pileated woodpecker | Dryocopus pileatus | Eastern meadowlark | Sturnella magna |

| Eastern kingbird | Tyrannus tyrannus | Loggerhead shrike | Lanius ludovicianus |

| Eastern wood-pewee | Contopus virens | Kentucky warbler | Geothlypis formosa |

| Northern parula | Setophaga americana | Veery | Catharus fuscescens |

| Baltimore oriole | Icterus galbula | Yellow-breasted chat | Icteria virens |

| Scarlet tanager | Piranga olivacea | Grasshopper sparrow | Ammodramus savannarum |

| Yellow-throated warbler | Setophaga dominica | Horned lark | Eremophila alpestris |

| Indigo bunting | Passerina cyanea | Black-throated green warbler | Setophaga virens |

| White-eyed vireo | Vireo griseus | Prairie warbler | Setophaga discolor |

| Ovenbird | Seiurus aurocapilla | Northern bobwhite | Colinus virginianus |

| Black-and-white warbler | Mniotilta varia | Prothonotary warbler | Protonotaria citrea |

| Common yellowthroat | Geothlypis trichas | Swainson's warbler | Limnothlypis swainsonii |

| SUBURBAN WINTER SPECIES | |||

| Yellow-rumped warbler | Setophaga coronata | Hermit thrush | Catharus guttatus |

| Dark-eyed junco | Junco hyemalis | Blue-headed vireo | Vireo solitarius |

| Yellow-bellied sapsucker | Sphyrapicus varius | Golden-crowned kinglet | Regulus satrapa |

| House wren | Troglodytes aedon | Purple finch | Haemorhous purpureus |

| White-throated sparrow | Zonotrichia albicollis | Evening grosbeak | Coccothraustes vespertinus |

| Ruby-crowned kinglet | Regulus calendula | Pine siskin | Spinus pinus |

| Note: Birds are arranged in order of occurrence, reading down each column by habitat. | |||

Table 20–3. Amphibians that may visit a yard.

| Common Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|

| FROGS AND TOADS | |

| American toad | Anaxyrus americanus |

| Fowler's toad | Anaxyrus fowleri |

| Southern toad | Anaxyrus terrestris |

| Northern cricket frog | Acris crepitans |

| Southern cricket frog | Acris gryllus |

| Cope's gray treefrog | Hyla chrysoscelis |

| Green treefrog | Hyla cinerea |

| Squirrel treefrog | Hyla squirella |

| Spring peeper | Pseudacris crucifer |

| Upland chorus frog | Pseudacris feriarum |

| Eastern narrowmouth toad | Gastrophryne carolinensis |

| American bullfrog | Lithobates catesbeianus |

| Green frog | Lithobates clamitans |

| Pickerel frog | Lithobates palustris |

| Southern leopard frog | Lithobates sphenocephalus |

| SALAMANDERS | |

| Marbled salamander | Ambystoma opacum |

| Spotted salamander | Ambystoma maculatum |

| Eastern newt | Notophthalmus viridescens |

| Southern two-lined salamander | Eurycea cirrigera |

| Blue Ridge two-lined salamander | Eurycea wilderae |

| Northern dusky salamander | Desmognathus fuscus |

| White-spotted slimy salamander | Plethodon cylindraceus |

| Atlantic Coast slimy salamander | Plethodon chlorobryonis |

If the landowner is unable or unwilling to control the problem, a number of private individuals or companies are authorized by the NCWRC to handle wildlife damage complaints. The NCWRC (866-318-2401) provides a list of Wildlife Damage Control Agents.

Permits are very rarely issued for endangered or protected species and must meet strict criteria. The executive director for the NCWRC may issue permits to take or possess an Endangered, Threatened, or Special Concern species according to regulations and policies in place (see 15A NCAC 10I .0102 for more information). However, when game animals cause substantial property damage during hunting season, landowners or lessees may obtain a hunting license and take animals on the property by any lawful means. During no-hunting seasons, game animals in the act of causing substantial property damage can be taken, without a permit, only by using firearms. Local ordinances, such as those regarding firearms within city limits, should be checked because they may have a bearing on the choice of control method.

When an animal is killed, it must be buried or otherwise disposed of in a safe and sanitary manner. The killing and disposal methods for bears, elk, and alligators taken must be reported to the NCWRC within 24 hours. 15A NCAC 10B .0106 (F).

Federal Regulations

A permit is normally required to take migratory bird species: waterfowl, mourning doves, hawks, blackbirds, woodpeckers, and most species of songbirds. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Animal Control Office should be contacted for control information and permit application forms:

USDA-APHIS/ADC

6301 E. Angus Drive

Raleigh, NC 27613 (919-856-4124)

Mail permit application forms to:

USFWS

PO Box 49208

Atlanta, GA 27613 (404-679-7070)

Table 20–4. Reptiles that may visit a yard.

| Common Name | Scientific Name |

| SNAKES | |

|---|---|

| Worm snake | Carphophis amoenus |

| Black racer | Coluber constrictor |

| Ringneck snake | Diadophis punctatus |

| Corn snake | Pantherophis guttatus |

| Rat snake | Pantherophis alleghaniensis |

| Eastern hognose snake | Heterodon platirhinos |

| TURTLES | |

| Common snapping turtle | Chelydra serpentina |

| Painted turtle | Chrysemys picta |

| Eastern box turtle | Terrapene carolina |

| Yellowbelly slider | Trachemys scripta |

Management Strategies to Reduce Damage

Many strategies exist that can be implemented and are quite effective in managing a nuisance wildlife species. If these strategies are implemented in the following order, often chemical or lethal controls become unnecessary.

Habitat modification—changes in habitat to make it less appealing, including removal of food or shelter

Exclusion—creating physical barriers to wildlife

Repellents—frightening, sound, taste, odor, or tactile sensation

Trapping—capturing the animal

Keep in mind that trapping may only be conducted during the legal trapping season for a given species or under an appropriate depredation permit. Trapped animals may be released alive at the site of capture; however, rules restrict the release of certain species onto other properties, and no releases are permitted onto federal or state owned lands. Consult the NC Wildlife Resources Commission for guidance prior to considering trapping as a management option.

Lethal control—killing the animal

Legal means vary by species and may include take during hunting seasons, take under a depredation permit, or take during the act of causing substantial property damage. See information below or consult the NC Wildlife Resources Commission for species-specific guidance.

Animals Commonly Encountered in Gardens, Lawns, and Landscapes

BIRDS—CROWS

Crows are 17 to 21 inches tall, shiny black, and make a distinctive “caw–caw” sound (Figure 20–7). Crows may pull up newly planted seeds or seedlings in the garden and eat ripe fruit and seeds. However, about a third of the crow’s diet is animal matter, including grasshoppers, caterpillars, grubs, spiders, and millipedes.

BIRDS—PIGEONS

In North Carolina, pigeons are non-native and unprotected.

Pigeons are crow-sized birds with slate-blue feathers and two black bars on the wings. The neck feathers have a greenish-purple sheen (Figure 20–8). Pigeons feed and roost in flocks. These birds can become a nuisance when they soil buildings, sidewalks, or window ledges with their droppings.

BIRDS—RED-WINGED BLACKBIRDS

Red-winged blackbirds are one of the most abundant birds in North America. They are 7 to 9 inches tall with a conical bill (Figure 20–9). Red-winged blackbird males have shiny black feathers and gold and red shoulder patches. Females have brownish feathers that can be mottled. Red-winged blackbirds may pull up newly planted seeds or seedlings in the garden and eat ripe fruit and seeds.

BIRDS—STARLINGS

In North Carolina, starlings are non-native and unprotected.

Starlings are about robin-sized with yellow beaks and gold-flecked, iridescent blue-black feathers (Figure 20–10). Their wings have a delta shape when in flight. They are found in all communities in North Carolina—from rural farms to more urban settings. They nest in holes in trees or other cavities. Starlings may pull up sprouting corn and other small grains and feed on insects, peanuts, fruits, berries, grains, and sunflowers. Most damage occurs in early morning and late afternoon. However, starlings also eat insects that may be harmful to plants such as larvae of Coleoptera (beetles) and Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies).

Management Strategies for Bird Species Listed Above

(Management recommendations for woodpeckers are listed separately in the next section)

Habitat Modification

- Thinning or pruning tree branches can discourage bird roosting.

- Spike strips can be placed where birds are known to roost (Figure 20–11).

- Corn hybrids with long husk extensions and thick husks are more resistant to damage by birds than other hybrids. Sunflower cultivars with heads that turn downward as they mature and seeds with thick hulls are less likely to be damaged.

Exclusion

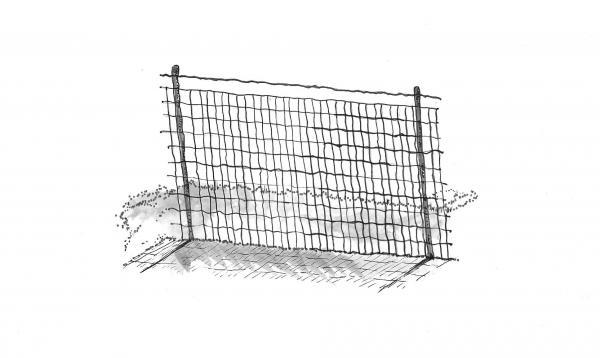

- In some situations, birds can be excluded by using chicken wire or netting. Netting should totally enclose the plants (Figure 20–12) because even a small hole can allow birds to enter and become trapped.

Repellents

- Visual. Scarecrows, plastic flags on posts, mylar foil streamers, effigies such as plastic snakes or owls (Figure 20–13), and predator balloons may offer temporary control.

- Noisemakers. Propane exploders, shell crackers, electronic sound devices. Local ordinances against noise pollution could prevent the use of this technique.

- Chemical repellents. See the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual for recommendations.

Trapping

- Not advised for crows or red-winged blackbirds.

- Mesh live traps baited with grain can be effective for trapping and removing pigeons and starlings.

Lethal control

- Firearms may be used to take crows and red-winged blackbirds in the act of destroying a landowner's or lessee's property.

- There is a legal hunting season for crows.

- There is no legal hunting season for red-wing blackbirds.

- To take crows out of season, and red-winged blackbirds not in the act of destroying property, property damage must be verified and a depredation permit obtained from NCWRC. (Refer to "Legal Requirements.")

- Pigeons and starlings have no protection under state laws. No permit is required, and there are no restrictions on the time of year they can be hunted. Be sure to observe local ordinances.

BIRDS—WOODPECKERS

There are several species of woodpeckers that are commonly found in the Southeast. Woodpeckers range in size from the crow-sized, red-crested, pileated woodpecker (Figure 20–14) to the 6-inch-long downy woodpecker (Figure 20–15). Most woodpecker damage is inflicted by the northern flicker or "yellow hammer," which is about 12 inches long. Male and female flickers have a brown and black striped back, white rump, a red patch on the head, and yellow under the wings and tails; the adult male has a black "mustache" not found in adult females (Figure 20–16). Other species causing damage in the Southeast are the red-bellied woodpecker (Figure 20–17), red-headed woodpecker (Figure 20–18), yellow-bellied sapsucker (Figure 20–19), and, occasionally, the hairy woodpecker (Figure 20–20).

Although woodpeckers may damage fruit, nut, and berry crops, these problems do not seem to be widespread. Also, because they eat insects, woodpeckers can be considered beneficial. Sapsuckers, which are considered a keystone species by many ecologists, often drill numerous 1⁄4-inch holes in healthy trees to feed on sap as well as insects. Tree sap is flowing in a difficult time of year for birds to find food so many other bird species such as kinglets, warblers, phoebes, and even hummingbirds follow behind sapsuckers and lap up sap or insects.

Problems caused by woodpeckers are most often related to damage to buildings and annoying noise. Male woodpeckers "drum" (peck) to proclaim a territory and attract a mate. Metal flashing, guttering, television antennas, and wooden surfaces on a house may serve as resonators and amplifiers for this drumming sound and may be selected by a woodpecker over trees.

Woodpeckers peck holes in natural wood siding such as cedar, juniper, cypress, and redwood. When nesting, woodpeckers may pull out some insulation from between walls and lay eggs in this space. A woodpecker that mistakes its reflection for a trespasser in its territory may attack a window. Woodpecker damage can usually be avoided without killing the birds if a property owner or lessee begins control measures early.

Management Strategies for Woodpeckers

Woodpeckers are classified as migratory nongame birds and are protected by the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In addition, the red-cockaded woodpecker is fully protected as an endangered species (Figure 20–21). Endangered species may not be killed or harassed. It is possible, however, to get a permit to kill other types of woodpeckers. Permits are issued by the US Fish and Wildlife Service upon recommendation of USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services personnel. A strong case must be made to justify issuance of a permit. In addition, a state permit may also be required for measures that involve lethal control or nest destruction.

Endangered species may not be disturbed. Other species, however, may be managed with the following techniques:

Habitat Modification

- If you suspect that insect infestation of home siding is attracting woodpeckers to a house, have the siding treated before trying to repel the birds. The drumming sound on metal and wooden surfaces can be deadened by placing padding behind a regularly used drumming board or covering metal drumming sites with burlap.

- Locate nest boxes and suet feeders in trees nearby to lure the woodpeckers away from the home.

- Building an alternate drumming site may reduce the amount of damage to the house. Securely fasten a cedar board to the pecking site and loosely attach a second board to one end of the first board. These two boards should overlap to form a flexible resonating surface. A simple hollow box may serve as an effective substitute.

- To stop woodpeckers from pecking on windows, pull down the shades or blinds or block the bird's reflection with cardboard.

Exclusion

- It is important to cover holes with sheet metal or 1⁄4-inch mesh hardware cloth as soon as the holes are detected. Wood putty should not be used as it will probably be pecked out.

- Staple polypropylene netting or screen wire near the rain gutter and angle it down toward the house to close off an area from woodpeckers.

Repellents

-

Scare tactics—Rubber snakes, hawk silhouettes, pie pans, tin can lids, mylar or aluminum foil streamers, and small windmills (suspended by string or fishing line under the eaves) may repel woodpeckers from houses as well as fruit and nut trees. A loud-playing radio in a window may scare the birds away. Place concave (enlarging) mirrors near damaged areas.

Lethal Control

- Woodpeckers are federally protected migratory species. A federal permit is required to take these birds for control of depredation.

- NCWRC does not require the issuance of a concurrent state depredation permit when a federal permit has been obtained nor do they require that the federal permit be countersigned by a NCWRC official.

- Birds killed for depredations must be turned over to a representative of the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS).

- The red-cockaded woodpecker is classified as an endangered species and may not be taken.

CATS

Domestic cats (Felis catus) include indoor-only, free-ranging indoor/outdoor, and feral cats (referred to as outdoor cats). Outdoor cats sometimes use garden beds as litter boxes- which can create health risks to humans and wildlife by spreading parasites and diseases.

Domestic cats are not native to the United States and, when allowed outdoors, can be harmful to native wildlife. They are skilled predators, contributing to the extinction of at least 63 species and killing over 2.4 billion birds and 12.3 billion mammals each year in the United States. Do not create wildlife habitat to lure birds and other wildlife to areas where there are outdoor cats.

Management Strategies for Cats

The best management strategy is to keep cats indoors and ask neighbors to keep their cats indoors. Open communication can prevent and resolve many conflicts.

Habitat Modification

-

Minimize the outdoor availability of water, food, and shelter.

-

Avoid feeding birds if outdoor cats are present.

-

Place trash in an enclosed area with lids tightly secured.

-

Remove items that can be used as shelter.

-

Mow grass and vegetation to reduce habitat for rodents.

Exclusion

-

Fences must be at least 6 feet high with 2-inch by 2-inch mesh and a curved 2-foot overhang.

-

Limit hiding areas and travel routes.

Frightening Devices/Repellents

-

Motion-activated sprinklers can be effective, but most frightening devices are not.

-

Although a few chemicals have US Environmental Protection Agency approval for repelling cats, there is no scientific evidence that they are effective.

Trapping

-

Cage traps are generally effective without being lethal.

-

Before attempting to trap cats, contact the local animal control agency, humane society, county animal shelter, and/or wildlife damage control agent for options.

Other Management Measures

- Contact the local animal control agency, humane society, county animal shelter, and/or wildlife damage control agent when considering other management strategies.

DEER, WHITE-TAILED

White-tailed deer may damage farm crops, gardens, trees, and shrubs. The severity of the problem varies with the deer population and the availability of other food. Deer browse on the tips, buds, branches, and foliage of ornamental trees, shrubs, and forest tree seedlings. Also, deer feed on corn, small grains, and vegetable crops, usually eating small, tender plants (most of the damage occurs during the first 10 days after germination). Because deer have no incisor teeth in the upper jaw, they tear vegetation away rather than cut cleanly. Vegetation damaged by deer has a jagged appearance (Figure 20–23). The split, sharp hooves of deer also leave distinctive hoofprints (Figure 20–24). Deer feed primarily at dawn, dusk, and nighttime, retreating to heavy cover the rest of the day. They feed exclusively on plant materials, and plantings near forest edges are most vulnerable.

Management Strategies to Minimize Deer Damage

Habitat Modification

- Unless very hungry, deer may not select medicinal plants, sticky or hairy leaves and stems, and foliage with a lemony or minty fragrance.

- Planting some of these plants near the garden borders may help deter deer.

Exclusion

- Plastic tree cylinders or woven-wire cylinders can be used to protect young trees and shrubs.

- Fencing significantly reduces deer damage if installed and maintained properly (Figure 20–25). The most effective type is a high-tensile electric fence. See the NCWRC for more information on fencing options.

Repellents

- Although human hair is an odor repellent that has provided limited success, no scientific evidence exists on its effectiveness.

- The faint rotting odor derived from mixing four eggs in a gallon of water and spraying the mixture on plants may repel deer. Fortunately, the smell is too faint for humans to detect.

- A formulation of 1 to 2 tablespoons of Tabasco sauce in 1 gallon of water has been shown to have limited effectiveness.

- Recent studies have shown ordinary bars of soap can reduce deer damage. Suspend a bar of soap from a tree using a mesh bag or pantyhose (Figure 20–26). Each bar protects an area of 1 square yard.

- See the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

- Be sure to read the label carefully as not all formulations are safe for use on food crops.

- The effectiveness of all repellents depends on the weather, the deer's appetite, and whether other food is available. New foliage that appears after treatment is unprotected. All chemicals should be applied according to the label's directions.

- Subsequent rain reduces a chemical’s effectiveness and requires retreatment.

- Repellents are more effective if they are applied before deer become accustomed to foraging on garden plants.

- Do not use mothballs. Mothballs (naphthalene) have been used by some gardeners trying to control deer and rabbits. This practice is illegal and potentially dangerous. It is illegal to use any pesticide in a manner inconsistent with the product label. Deer and rabbits are not listed on the label for mothballs. Small children and pets can be poisoned by eating mothballs.

Lethal Control

- There are specified seasons when it is a legal to hunt deer.

- To take deer out of season, property damage must be verified and a depredation permit obtained. (Refer to "Legal Requirements.") Deer taken under a depredation permit must be taken according to restrictions outlined on the permit itself.

- The only legal way a deer may be taken out of season, without a depredation permit, is if the deer is shot with a firearm while in the act of causing property damage. Refer to "Legal Requirements" and/or contact the NCWRC for additional information.

- Live trapping and removal of deer is not a practical way to control deer damage. The amount of labor, number of traps, and time necessary to remove enough of the herd to influence the problem are prohibitive. The welfare of target and non-target animals is also a challenge when dealing with live traps and relocation.

- An annual harvest (shooting) of does (female deer) and bucks (male deer) maintains a population within the carrying capacity of the herd's range. Landowners should provide sufficient opportunity to allow hunters to harvest the deer. Shooting is effective either by legal hunting during the open deer season (which requires a hunting license), by the landowner or lessee when deer are caught in the act of depredation, or as authorized by a wildlife depredation permit.

GROUNDHOGS (WOODCHUCKS)

The groundhog, also known as a woodchuck, is a lowland creature living along the edge of the woods or in open plains (Figure 20–27). Groundhogs are found in both the mountain and piedmont areas of North Carolina. They hibernate during the winter. Groundhogs are usually brownish-gray, but some individuals may be white or black. Their tails are relatively short, hairy, and somewhat flattened. A groundhog’s body is supported by strong stout legs. Black claws on the front feet are long and curved to make digging through the soil easy. They are good climbers and may be seen in trees, surveying their surroundings or escaping from predators. Their primary predators include hawks, owls, foxes, coyotes, dogs, bobcats, weasels, and humans.

Groundhogs are mostly vegetarian. Groundhogs select trees, legumes, vegetables, and grasses. They can also gnaw on the bark of ornamental shrubs and fruit trees and in some situations cause enough damage to kill the plant. They will, when necessary, feed on the occasional insect or worm.

Their burrows are quite large, averaging 10 to 12 inches in diameter. The amount of dirt excavated when digging a burrow can be substantial and unsightly in a landscape. These burrows and the tunnels that accompany them can cause problems like twisted ankles or broken legs for humans, livestock, or pets.

Management Strategies to Minimize Groundhog Damage

Habitat Modification

- High levels of human activity can keep groundhogs away from a property.

- Once a groundhog is gone, fill in the den and tunnels to prevent another groundhog, skunk, or rabbit from taking up residence.

Exclusion

- Practical for small home gardens, but not for a large acreage.

- Fencing has the added advantage of keeping out rabbits, dogs, cats, and raccoons.

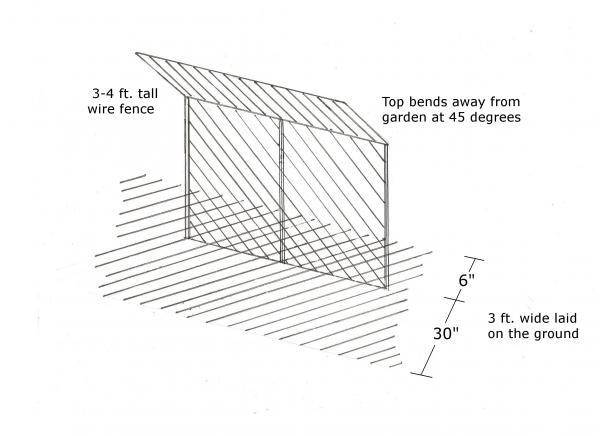

- Groundhogs are good climbers, so fences must be electric, woven, or made of welded wire, and extend at least 3 to 4 feet tall with a 45-degree angle at the top to discourage groundhogs from climbing over (Figure 20–28).

- The fence should also be buried 12 inches to 14 inches underground to prevent groundhogs from digging under. Either the fence material can be bent at a 90-degree angle to the outside (away from the protected area) and extend for 6 inches or a separate piece of fencing material can be buried perpendicular to the fence and extended away from the garden 30 inches.

- In some cases, electric wire alone placed 4 to 5 inches above the ground has been effective.

Repellents

- Using frightening devices such as effigies (scarecrows or plastic owls) can be somewhat effective, but they must be moved regularly.

- Some people claim that fox urine, ammonia, or smells of other predators may repel groundhogs. There is no research-based information to support these claims.

Lethal Control

- Groundhogs can be shot year-round. There is no closed season or bag limit.

- During the legal trapping season, a North Carolina trapping license is required to use a body-grip trap or to trap and shoot groundhogs. Outside of the legal trapping season a depredation permit is required to use a body-grip trap or for trap and shoot for groundhogs.

- Groundhogs can be released alive at the site of capture, but cannot be relocated off site.

MOLES: EASTERN, HAIRY-TAILED, AND STAR-NOSED

Three species of moles occur in North Carolina: the eastern mole (Figure 20–29), the hairy-tailed mole (Figure 20–30), and the star-nosed mole (Figure 20–31). Both the eastern mole and the hairy-tailed mole are classified as pests in North Carolina when tunneling in managed turf in the following areas: residential, commercial, government property (excluding federal and state parks), golf courses, driving ranges, golf instruction facilities, sod farms, athletic fields or visitor centers, and cemeteries. Pastures are not considered managed turf.

All moles are similar in appearance. The head has a long, hairless, pointed snout; lacks external ears; and has small, barely noticeable eyes. Moles have a short neck, and the muscular front legs support broad, heavily clawed feet. The animal's hind legs, feet, and tail are small. The fur is short, velvety, dark-gray to black, and covers most of the animal. Total length ranges from 5 inches to 8 inches. Contrary to popular belief, moles are not in the rodent family.

Moles are seldom seen aboveground, but their presence can be observed by ridges in lawns, gardens, and ornamental beds created by the moles tunneling in search of food. Moles must cover a wider area than most underground animals to satisfy their food needs. Most runways are shallow burrows dug just beneath the surface and may or may not be used again. Slightly deeper tunnels are reused as main highways between the mole's home and feeding grounds. Other animals may use the tunnels made by moles.

Many gardeners consider moles an asset in the landscape as moles loosen the soil and feed on garden pests. Moles are insectivorous, which means they eat insects—not vegetation. A mole can eat daily almost its own weight in food, which consists almost entirely of earthworms and insects, including white grubs, ants, beetles, and other subterranean insects. Roots, bulbs, and tubers are not eaten by moles but may be damaged during digging activity. Extensive tunneling may lead to drying out of shallow-rooted lawns, flowers, vegetables, and shrubs or expose them to later attack by small rodents.

Moles are more active during rainy periods in summer. Tunnels made during dry weather tend to be shallow because moles follow the courses of earthworms.

The eastern mole, the probable culprit when lawns and gardens are damaged, is usually solitary; although the female shares her burrow with her young while they mature (approximately eight weeks).

Management Strategies for Eastern and Hairy-Tailed Moles

Habitat Modification

- Packing the soil down where tunnels are evident destroys burrows and can kill moles if done in the early morning or late evening.

- Reducing soil moisture by holding off on irrigation can be somewhat effective.

Exclusion

- Exclusion methods are generally effective only in small, high-value areas.

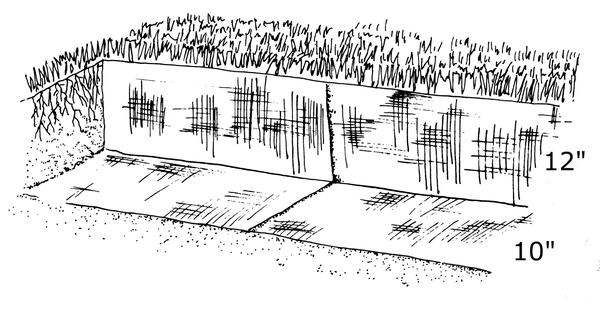

- A sheet metal or hardware cloth fence may be used to protect areas such as seedbeds. The fence should start at the ground surface and go to a depth of at least 12 inches and then bend outward an additional 10 inches at a 90-degree angle (Figure 20–32).

Repellents

- Although some electronic, magnetic, and vibrating devices are advertised to frighten or repel moles, none are shown to be effective.

- Placing hair, chewing gum, bleach, razor blades, broken glass, thorny rose branches, and other sharp objects in mole tunnels has not been shown to be effective and is not recommended.

- The so-called mole plant (caper spurge, Euphorbia lathyrishas) been advertised as a living mole repellent, but there is no research to support the claims.

Lethal Control

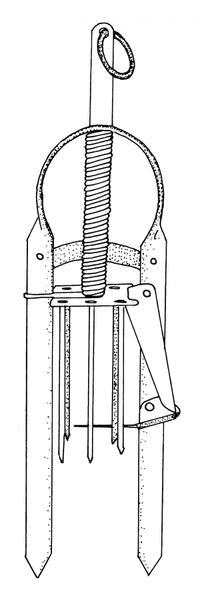

- A depredation permit is required prior to trapping Eastern and Hairy-Tailed moles. A frequently used runway can be located by caving in short sections of visible tunnels and checking them daily to see which ones are re-opened. Runways tend to be long straight tunnels, and there is no need to set traps on short, twisting tunnels. Set a spear-type trap (Figure 20–33) over a depressed portion of the surface tunnel. As a mole moves through the tunnel, it pushes upward on the depressed tunnel soil and trips the trap’s trigger. One or two traps should be enough for the average lawn because the tunneling is probably caused by only a few moles.

- There are approved mole Rodenticides registered with the Environmental Protection Agency and the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services. Registered pesticides can be found by going to Pesticide Registrations or Chapter IX of the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual, “Animal Damage Control." Also, landowners may contact the NC Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services, Pesticide Section or their local Cooperative Extension center for information on currently approved pesticides and legal application. Rodenticides used to control these species must be applied in specifically protected bait stations to minimize the hazards to non-target species (including children and pets). Before purchasing and using a pesticide read the DIRECTIONS FOR USE on the actual label.

STAR-NOSED MOLES

The star-nosed mole has a distinctive flesh-colored ring of tentacles around its nose. Its tail is also distinctive with concentric rings of short, coarse hair. The star-nosed mole is a state listed species of Special Concern and has not been classified as a pest so management options are different.

Management Strategies for Star-nosed Moles

Habitat Modification

- Packing the soil down where tunnels are evident destroys burrows and can kill moles if done in the early morning or late evening.

- Reducing soil moisture by holding off on irrigation can be somewhat effective.

Exclusion

- Exclusion methods are generally effective only in small, high-value areas.

- A sheet metal or hardware cloth fence may be used to protect areas such as seedbeds. The fence should start at the ground surface and go to a depth of at least 12 inches and then bend outward an additional 10 inches at a 90-degree angle (Figure 20–32).

Repellents

- Although some electronic, magnetic, and vibrating devices are advertised to frighten or repel moles, none are shown to be effective.

- Placing hair, chewing gum, bleach, razor blades, broken glass, thorny rose branches, and other sharp objects in mole tunnels has not been shown to be effective and is not recommended.

- The so-called mole plant (caper spurge) has been advertised as a living mole repellent, but there is no research to support the claims.

Lethal Control

- There is no open hunting or trapping season for star-nosed moles.

- A depredation permit obtained from the Executive Director of the NCWRC is required to trap star-nosed moles and is only issued when substantial damage has occurred (Refer to "Legal Requirements.") Contact NCWRC 866-318-2401.

RABBITS

Eastern cottontail rabbits eat a wide variety of plants, including grasses, clovers, carrots, lettuce, peas, beans, strawberries, and beets (Figure 20–34). They do not seem to like corn, squash, cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and gourds, which could be planted near the garden edges. Rabbits gnaw the bark on the stems and lower limbs of ornamentals and fruit and forest trees. Rabbits select apple, raspberry, blackberry, cherry, and plum. Ornamental plants that are often damaged include sumac, rose, tulip, basswood, dogwood, honey locust, red maple, sugar maple, and willow. Rabbits may completely girdle stems, thus killing the tree or shrub. The thicker, rough bark of older trees often discourages rabbits.

Rabbits have incisors in both the upper and lower jaws so that rabbit-damaged vegetation is cut cleanly (Figure 20–35) rather than torn away. Deer-damage vegetation has a jagged appearance(Figure 20–23).

Rabbits feed just before sunrise and just after sunset, but may be active during the day. They live in fence rows or at the edge of fields and rarely live in dense forests.

Management Strategies for Rabbits

Habitat Modification

-

Rabbit habitat can be reduced by removing brush piles, weed patches, dumps, stone piles, and other debris. Controlling vegetation along ditch banks and fence rows should help.

Exclusion

- Small areas such as gardens can be protected from rabbits with a 1-inch mesh wire fence at least 18 inches to 24 inches high. If snow depth nears or exceeds the height of the fence, it will be ineffective. The bottom edge of the fence should be staked or buried at least 6 inches to prevent burrowing.

- Electric fences with strands placed at 4, 8, and 12 inches from the ground may also be effective.

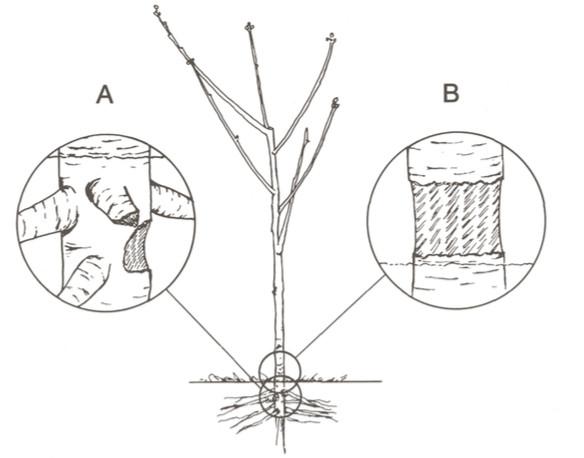

- Trees can be protected by cylinders of 1⁄4-inch mesh hardware cloth set firmly in the ground surrounding the trunk (Figure 20–36). The cylinders should be at least 18 to 24 inches high, but again, average snow depth must be considered. Commercial tree wraps and plastic guards may be used to prevent gnawing damage.

Repellents

- Dried blood meal sometimes protects flower beds, but it could attract dogs.

Lethal Control

- Lethal control of rabbits is very rarely necessary.

- Usually, exclusion solves the problem.

- An open hunting and box-trapping season is established for rabbits. Annual harvest during the open season may help avoid high populations that increase damage problems.

- A North Carolina hunting license is required to take rabbits during the legal hunting season. To take rabbits out of season, property damage must be verified and a depredation permit obtained. (Refer to "Legal Requirements.")

RACCOONS

Raccoons may eat grains, acorns, nuts, fruits, or vegetables (melons). They are heavy predators of corn, especially when the kernels are in the milking stage. Raccoons are omnivorous: they eat snails, frogs, insects, small mammals, garbage, birds, and eggs. They are active mainly at night and spend the day in hollow logs, rock cavities, culverts, and sometimes burrows. They primarily occupy areas near streams, lakes, and marshes. Raccoons are attracted to gardens, pet food, bird food, and garbage (Figure 20–37).

Management Strategies for Raccoons

Habitat Modification

- Removing a raccoon's day cover (hollow trees and logs) from areas immediately next to the control areas may force them to find cover and food elsewhere.

- Be aware that removal of snags, or dead trees, has the negative effect of reducing native bird habitat.

- Always feed pets indoors. Store pet food, bird food, and garbage inside or in sealed containers that cannot be opened by raccoons.

- Immobilize garbage cans, secure the lids, and follow proper sanitation methods.

- Raccoons actively use bird feeders. If there is a raccoon problem, consider a temporary suspension of bird feeding.

Exclusion

- A 2-inch mesh wire fence with an electrified strand can be used around gardens. The fence should be 4 feet high and run 6 inches below ground level and 18 inches outward at the base to prevent burrowing (Figure 20–38).

- Bags or netting can be placed over ripening crops such as corn cobs or peaches (Figure 20–39).

Repellents

- No repellents recommended.

Lethal Control

- Raccoons are considered a furbearing animal in North Carolina.

- A North Carolina hunting or trapping license is required to take raccoons during the legal hunting or trapping season.

- To take raccoons out of season, property damage must be verified and a depredation permit obtained (refer to Legal Requirements).

RATS, NORWAY

Rodents can be a challenge in both urban and rural settings, but, vigilance in applying integrated pest management strategies can keep populations low. Knowing some of the key characteristics of rats helps in developing a management plan. They can climb most surfaces and jump up to 36 inches. They are shy, but also inquisitive, initially avoiding new objects, but in time investigating them. Rats are nocturnal—out from dusk until dawn. They are not active the entire time but have multiple periods of activity at night. Their poor eyesight causes them to rely on hearing, touch, and scent. Rats’ incisors grow so rapidly they must constantly gnaw on everything to wear them down. Rats begin to breed at three months of age, producing up to 12 rats per litter and four to six litters per year. A pair of rats and their offspring could produce 1,500 more rats in only one year if they all survived. Their average lifespan is one year. Adult Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) range from 12 to 18 inches long, nose to tail tip (Figure 20–40). Their gray to brown bodies are compact and heavy. They have relatively small eyes and ears, and their tails are generally about half their body length. Norway rats are prodigious burrowers. They eat garbage, meat, fish, cereals, seeds, pet food, and a wide variety of other substances. To determine if there is a problem, look for these signs: evidence of gnawing, rat droppings (capsule shaped and 1⁄2-inch to 3⁄4-inch long), tracks, and large burrows along building walls.

Management Strategies for Norway Rats

These strategies are most effective when there is a community-wide effort.

Habitat modification

- Minimize nesting sites by removing junk and storing materials 12 to 18 inches off the floor and away from walls.

- Limit food by storing bulk birdseed, chicken feed, and other potential sources of food in metal containers. Store chicken feed in a metal container each night. Feed pets indoors. Remove spilled seed from beneath bird feeders. Clean up spilled food. Use a tight lid on garbage cans.

- Practice good sanitation. Well-swept floors and mowed turf make it easier to detect problems and also force rats into exposed settings, making them more vulnerable to predators such as dogs and owls.

Exclusion

- Make structures rodent proof. Seal off all potential entryways.

Repellents

- None proven effective.

Lethal Control

- Rodent-killing, as the only control strategy, is expensive and effective for only a short while. Unless the conditions that allowed the rats to thrive are changed, new rats will soon move in.

- Control is most effective in winter when rat populations are lowest.

- Unless the rodent infestation is severe, it is best to sanitize and rodent-proof prior to killing rodents.

- When trapping, traps may be baited or not. Bacon, peanut butter, bread, and nutmeats make suitable baits. Place traps in areas of rodent activity, 15 to 30 feet apart, in places that are inaccessible to pets and children. Traps have several advantages over rodenticides:

- They are more affordable as they can be used many times.

- There is no chance of accidentally poisoning a child, a pet, or another non-target animal.

- The rat is killed instantly in the trap.

- There is no chance that the trapped rat will provide an unintended dose of poison to a hawk, owl, or another predator.

- There is no chance a trapped rat will crawl inside a wall to die and decompose.

- To use chemical bait, see the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual. All chemicals should be applied according to the label's directions.

SNAKES

Snakes in the garden may cause concern for some people, but often the snake is not causing any harm and may be one of the gardener's best friends. Snakes help keep rat, mice, vole, and rabbit populations in check. Snakes are seen most often in the spring or fall as they search for food or move to and from hibernation areas. They are frequently associated with small mammal habitats because rodents are primary food sources for many snake species.

Several venomous snakes, including the copperhead (Figure 20–41), cottonmouth (also known as water moccasin), three rattlesnake species, and eastern coral snakes are found in North Carolina.

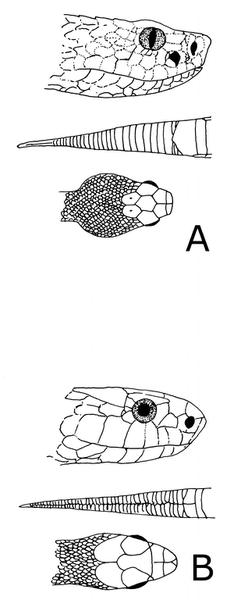

When snakes are observed on your property, we recommend keeping a safe distance unless you can positively identify the species as being non-venomous. Wild snakes often bask in the sun and this is when they become highly visible. In most cases, the snake will move on by itself. It can be very difficult to differentiate between venomous and non-venomous snakes. As a general guideline, the three rattlesnake species are pit vipers and can be identified by a pit between and slightly below the eye and nostril, long movable fangs, a vertically elliptical pupil, and a triangular head (Figure 20–42). Nonvenomous snakes have two rows of scales on their tails, while venomous snakes have one row of scales. The coral snake is another venomous snake that can sometimes be found in the southeastern part of the state, although it is extremely rare. It is recognized by its distinctive pattern of red and black rings separated by a yellow ring (Figure 20–43). We do not recommend handling or killing any snake. For help in identifying snakes, Davidson College has created a free app for Apple iPhones (it can be downloaded from iTunes) and has multiple pictures of each species of snake in North Carolina.

Strategies for Discouraging Snakes

Habitat Modification

- Reduce cover and food supply by mowing closely around homes, gardens, and storage buildings.

- Store firewood and lumber away from the house and preferably elevated off the ground.

- Reduce mulch layers around shrubs to discourage small animals.

- Close cracks and crevices in buildings and around pipes and utility connections with 1⁄4-inch mesh hardware cloth, mortar, or sheet metal.

Exclusion

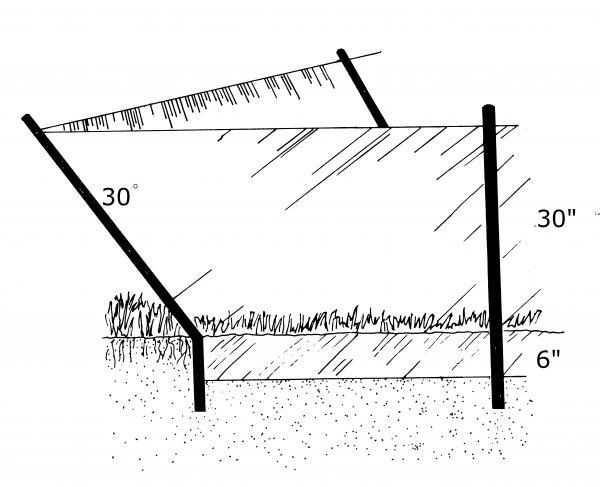

- Small areas can be protected with a snake-proof fence made of 1⁄4-inch mesh wire screening built up 30 inches and buried 6 inches underground. It is slanted at a 30-degree angle from top to bottom (Figure 20–44). The supporting stakes must be inside the fence, and any gate must fit tightly.

- The cost of the fence can make it impractical to protect the entire garden or yard. Tall vegetation just outside the fence must be removed.

Repellents

- Repellents are not effective.

Trapping

- Not advised or effective.

SQUIRRELS

The four most abundant tree squirrels (Figure 20–45) in North Carolina are the gray squirrel, fox squirrel, red squirrel, and southern flying squirrel. Gray squirrels are about 16 to 20 inches long with gray fur and a lighter underside. Red squirrels are 11 to 14 inches long and have reddish fur and a white belly. Southern flying squirrels are 9 to 14 inches long with brown fur and white underside. Fox squirrels are 19 to 29 inches long and have three basic color phases: red, gray, and black. In North Carolina, gray and flying squirrels usually cause depredation problems. Squirrels are agile and can jump 6 to 8 feet laterally. This makes control more difficult.

Squirrels eat a variety of foods including fruits, seeds, nuts, buds, shoots, insects, and fungi. They also pull or dig up corn plants and eat stored corn. In late winter and early spring, they often destroy the growing tips of young trees and shrubs. Much of their diet is made up of tree seeds (nuts), which are often stored. Broken and half-eaten nutshells beneath pecan and other nut trees indicate squirrel (or possibly blue jay) depredation. Studies show that squirrels do not "remember" where nuts are buried but happen to smell them while foraging. Nuts that are left covered often germinate and grow.

Squirrels eat from bird feeders. When other foods are in short supply, squirrels may damage trees by debarking and cutting an excessive number of buds. Squirrels usually build nests from leaves or den in natural tree cavities or crotches of branches. Squirrels sometimes den in buildings and cause damage by gnawing through siding and electrical wires (creating a fire hazard) and breaking weather seals. Although squirrels do not hibernate, they may remain in the nest for days during adverse weather. Most are diurnal, with the greatest activity in the early morning or late afternoon hours. The flying squirrel, however, is nocturnal (active at night).

Management Strategies to Minimize Squirrel Damage

Habitat Modification

- Use squirrel-proof bird feeders. Some have domed tops that prevent access (Figure 20–46). Others have a weighted cage on the outside that slides down over the holes in the feeder when a squirrel hangs from it to feed. Birds are too light to make the cage slide down.

- To reduce squirrel access to roofs and homes, remove overhanging branches and trim limbs at least 6 feet from homes and buildings.

Exclusion

- Isolated, high-value trees can be "squirrel proofed" by placing 2-foot-wide metal bands around the tree, 6 feet off the ground (Figure 20–47). Trim overhanging branches to prevent access from nearby trees. This method does not work when trees are closely planted and have overlapping branches.

- High-value crops can be protected by building a fence of 1-inch mesh wire. The fence should be at least 30 inches high and extend 6 inches below the ground with an additional 6 inches bent outward (at 90 degrees) to discourage burrowing. At least two electrified strands (one 2 to 6 inches above the ground and the other at the fence height) should be set off the fence about 3 inches.

- Newly planted bulbs can be protected with 1-inch mesh poultry wire. Dig a trench slightly deeper than the desired depth of planting and fit the poultry wire in the bottom. Add soil and plant the bulbs. Place another strip of poultry wire over the plantings so that the bulbs are completely encased, then finish covering with soil.

Repellents

- No repellents recommended.

Trapping

- With proper depredation permits, squirrels can be live trapped with wooden or wire box traps for relocation. Bait the traps with peanut butter rolled in oats, nut meats, pumpkin or sunflower seeds, or dried prunes. Tie the trap door open for several days to get squirrels accustomed to feeding in the trap. Wear gloves and do not handle the squirrel. Squirrels can be released onto other private property with written permission of the landowner. They cannot be released onto any government properties or onto other private property without permission.

Lethal control

- North Carolina hunting seasons are established for fox and gray squirrels, although, some counties prohibit the hunting of fox squirrels. A hunting license is required during the open season.

- During the closed season, a landowner or lessee may apply for a depredation permit if they are experiencing squirrel damage (refer to Legal Requirements).

VOLES: PINE AND MEADOW

Four kinds of voles occur in North Carolina: pine, meadow, rock, and red-backed. These small mammals, commonly mistaken for mice, live in fields, orchards, and shrub habitats. Only pine and meadow voles causing damage in or immediately adjacent to cultivated lands--forest plantations, ornamentals nurseries, orchards, or horticultural plantings in institutional, recreational, and residential areas--are classified as pests (Figure 20–48 and Figure 20–49). These voles are becoming more common as the use of natural areas in the landscape increases. In horticultural plantings, pine and meadow voles can cause damage by eating flower bulbs, girdling the stems of woody plants, and gnawing roots. Plants not killed outright may die later due to root damage or disease organisms that entered through wounds created by the vole.

Pine voles have small eyes and ears that are hidden by their reddish-brown fur. A pine vole’s tail is shorter than its hind legs. The adult pine vole is about 3 inches long and weighs 1 ounce or less. Pine voles spend most of their life underground in burrow systems. Unlike moles, voles are herbivores and feed on plant roots, flower bulbs, and the growing tissue (cambium) of tree roots. They eat bark primarily in fall and winter.

A pine vole tends to stay in an area as small as 1,000 square feet for its entire life. At night, they come aboveground and feed on fruit and tender green vegetation. Soils with substantial clay content are more likely than sandy soils to support pine vole populations because clay permits relatively permanent tunnel systems and nest chambers.

Pine voles damage trees and plantings below the ground (Figure 20–50). When the damage to a particular plant is extensive, the plant will be severely weakened and may die. The trunks of small trees or shrubs may be severed from the roots, making it possible to pull the top of the plant out of the soil. Or the plant may fall over by itself.

Upon close inspection of the plant, gnawing marks can be seen just under the soil line. In apple orchards, the damage to the tree may not be sufficient to kill the tree, but damaged trees produce less fruit. Careful observation beneath the tree may reveal piles of earth (3 to 4 inches wide) and tunnels that are about 11⁄2inches in diameter. If pine voles are living under the tree, a network of tunnels approximately 3 inches under the soil can be located by probing with a 1⁄2- to 3⁄4-inch diameter stick or rod.

The meadow vole’s eyes are not covered by fur, and its ears (partly covered by hair) are visible. The tail is longer than the hind legs. The fur is dark brown, often silvery on the underside. The adult meadow vole ranges from 31⁄2 to 5 inches long and weighs 1 to 21⁄2 ounces. Meadow voles spend most of their lives aboveground, living in and feeding on grasses. They have larger home ranges than pine voles and may travel as far as 1⁄4-mile in a week. The typical habitat for meadow voles is a grassy meadow, particularly in places where grasses grow in clumps. Tall fescue areas in orchards, lightly grazed pastures, and old fields are typical habitats. Signs of meadow voles are found mostly aboveground in taller grasses and cover. Look for trails in the grass and grass clippings, and check for feces at the base of large clumps of grass. The feces, shaped like wheat grains, may be brown or green in color and are frequently left in small piles. Typically, meadow voles girdle trees and saplings at the ground line (Figure 20–51). Close inspection of the damage reveals paired grooves left by their chisel-like teeth. The grooves are about 1⁄16-inch wide. Girdling completely around the tree trunk kills the plant, so any indication of aboveground damage is cause for instituting a control program.

Rabbits chew on young trees, but their girdling begins several inches above the soil line. Rabbits have much larger incisor teeth than voles, which is reflected in the size of grooves on the girdled tree. Rabbit damage can be controlled with a plastic tree guard, but these devices do not prevent meadow vole damage.

Testing for Voles

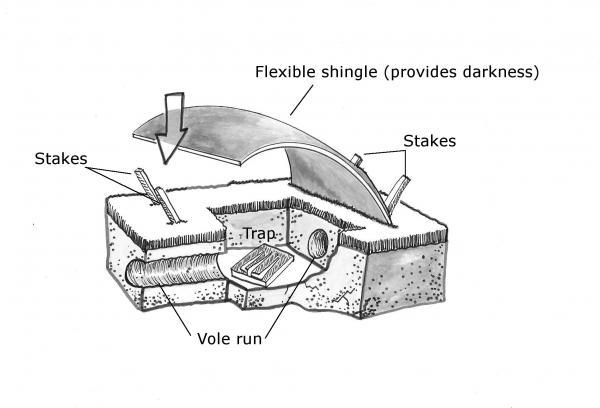

The apple sign test was developed to monitor vole populations in commercial orchards. The test permits the grower to detect the vole populations before the damage becomes severe. It also reduces the exposure of nontarget animals to control activities. Because the test shows where control is needed, areas without voles are not treated, saving time, money, and environmental risk. Conduct the apple sign test in the fall and spring each year. Sketch a map of the grounds, especially if plantings are extensive. Prepare enough brown shingles or 1- to 2-inch thick pieces of board (painted to match the background color of the flower garden or plantings) to scatter them strategically along the edges and throughout plantings at 15-foot intervals.

Place a shingle on the ground, if possible over a hole caused by a vole. To monitor for meadow voles, the shingle must be rounded in a tent-like fashion or propped up 3 to 4 inches off the ground so that the animal can go under it. After five days, place a 1⁄2-inch cube of apple under each shingle. After 24 hours, check to see if the apple has been removed or eaten. Leave the shingles in place for future monitoring. When monitoring has been completed, a control action can be directed to the locations where vole damage may occur rather than to the entire planting.

Management Strategies for Voles

Habitat modification

- Remove mulch from within a foot of the trunk of a plant. This prevents the vole from sneaking in under the mulch. Instead, the vole must use an exposed approach that is more dangerous and less attractive to it.

- Reduce or remove grass thatch to deter meadow vole populations. Close mowing prevents meadow voles from hiding from their predators (hawks, owls, foxes, cats, and dogs) and may prevent populations from becoming established.

- Soil cultivation disturbs burrows and reduces plant cover.

Exclusion

- Wrapping seedlings and young trees in hardware cloth cylinders can exclude voles. The mesh should be 1⁄4-inch or less. Bury the wire 6 inches to keep voles from burrowing under the cylinder.

- Creating a gravel barrier several inches wide on the bottom and sides of the plant’s root zone may provide protection.

Repellents

- None proven effective.

Lethal Control

- A depredation permit must be obtained from the NCWRC before trapping voles. Trapping is an effective way to determine if one or both kinds of voles are present.