Outline

Edible Weeds

Poisonous Weeds

How Do Weeds Spread and Propagate?

Monocot versus Dicot

Weed Management: The Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Approach

Cultural Management

Weed Disposal

Mechanical Management

Biological Management

Chemical Management

Objectives

This chapter teaches people to:

- Understand the basics of weed biology, including weed life cycles and reproductive strategies.

- Use weed identification tools.

- Understand how to apply integrated pest management (IPM) strategies to prevent and manage weeds.

What Are Weeds?

A weed is, in essence, "a plant out of place.” Some plants (including poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac) are easily recognized as harmful. Other plants, however, may or may not be considered weeds depending on one’s viewpoint. Dandelions, wild violets, and goldenrod, for example, may be weeds to one person but attractive wildflowers or food to another. Many of our most common weeds were accidentally introduced with crop plants our ancestors brought to this country. Other plants were intentionally introduced, and only later were categorized as weeds. Crabgrass, for example, was among the first grains cultivated in Europe during the Stone Age and was probably introduced to the United States in fodder. Some varieties were later introduced here as forage crops and continue to be cultivated. Similarly, kudzu was introduced for soil stabilization and as a possible pasture plant, and the multiflora rose was introduced and promoted as a living hedge. Some ornamentals, such as English ivy, bamboo, Japanese knotweed, and water hyacinth, have been intentionally planted in landscapes only to "escape" and become invasive weeds in natural areas.

Weeds compete with crop and landscape plants for water, nutrients, and sunlight. Weeds can reduce crop yield, affect the aesthetic qualities of landscapes and the functionality of sports turf, and displace native flora in natural areas. Weeds sometimes attract or harbor harmful insects or serve as alternate hosts for plant pathogens. Many weeds, such as ragweed, are wind-pollinated and produce copious amounts of pollen, which can cause hay fever.

Many weeds are ornamental and some are edible, but certain ones can be poisonous. Regardless of their other qualities, by definition all weeds are plants growing where they are unwanted.

Edible Weeds

Edible weeds can be delicious, home-grown, and economical additions to any dinner table. We have been conditioned to think of weeds as pests to be eradicated from tidy landscapes. In fact, some weeds are nutritional powerhouses containing vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Eating weeds from your yard can motivate you to weed and take advantage of growing food that does not require planting, watering, or fertilizing.

Although many weeds are edible (Table 6–1), many are not. It is important to correctly identify any weed you plan to eat and also which parts of each weed are edible. While some parts may be edible, others can be toxic. Edible weeds can be enjoyed in a variety of ways. Leaves can be eaten raw and added to salads, or sautéed, steamed, or boiled. Roots can be boiled or roasted. Teas can be made from dried flowers, leaves, or roots. Edible flowers can adorn salads or desserts or be infused to make tasty oils or vinegars.

Here are some guidelines for eating weeds:

- Proper identification is essential.

- Use plants that have not been sprayed with fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides.

- Avoid weeds growing on roadsides where exhaust from vehicles can leave residues on foliage.

- Young tender weeds are usually less bitter than mature weeds.

- After harvesting, wash weeds with slightly cool, soapy water and rinse thoroughly before eating them.

- Limit consumption to small amounts of one type of weed at a time to be able to pinpoint any allergic reactions.

Table 6–1. Edible Weeds1

| Common Name | Botanical Name | Edible Part |

|---|---|---|

| Burdock | Arctium L. | Roots |

| Chickweed | Stellaria media | Young shoots and tender tips of shoots raw, cooked, or dried for tea |

| Chicory | Cichorium intybus | Leaves and roots |

| Clover | Trifolium L. | Leaves sautéed; flowers raw, cooked, or dried for tea |

| Creeping Charlie | Pilea nummulariifolia | Leaves, often used in teas |

| Dandelion | Taraxacum officinale | Leaves, roots,and flowers |

| Garlic mustard | Alliaria petiolata | Roots and young leaves |

| Japanese knotweed | Reynoutria japonicaa | Young shoots less than 8 inches long and stems (Do not eat mature leaves.) |

| Lambsquarters | Chenopodium album | Young leaves and stems |

| Little bittercress or shotweed | Cardamine breweri | Whole plant |

| Mallow | Malva neglecta | Leaves and seeds |

| Nettle | Urtica dioica | Young leaves (must be cooked thoroughly or dried for tea) and seeds |

| Pigweed or wild amaranth | Amaranthus L. | Leaves and seeds |

| Plantain | Plantago major | Leaves (remove stems) and seeds |

| Purslane | Portulaca L, | Leaves, stems, and seeds |

| Sheep’s sorrel | Rumex acetosella | Leaves |

| Violets | Viola sororia | Young leaves and flowers |

| Wild garlic | Allium canadense | Leaves and roots |

| 1 For images and descriptions see The Extension Gardnener Plant Toolbox. | ||

Poisonous Weeds

Serious illness or even death can result when poisonous weeds are eaten. The entire plant may be poisonous, or the toxins may be confined to only specific parts (leaves, roots, fruit, or seeds). In addition, the plant may be toxic throughout its life cycle or only at certain stages. It is primarily young children who are poisoned by plants. Prone to put everything in their mouths, children are particularly attracted to colorful berries and seeds. No one should ever put any part of a plant in his or her mouth unless the plant has first been identified as edible. Cocklebur seeds and young seedlings are poisonous to humans and livestock, but burdock seedlings are edible. All parts of jimsonweed (Datura stramonium) (Figure 6–1) contain toxic alkaloids that cause hallucinations, convulsions, or death; contact with jimsonweed sap causes a skin rash on some people. Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) leaves are poisonous unless carefully prepared (harvest only young leaves and change the water when cooking). Pokeweed roots are quite poisonous, and the berries, though less poisonous, also contain the toxin.

For additional information on poisonous plants, refer to NC State Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox. Another helpful guide to poisonous plants is Plants Poisonous to Livestock in North Carolina, available through NC State Extension.

Possible poisoning cases should be referred to the nearest Poison Control Center. The Carolinas’ Poison Control Center can be reached by phone at 800-222-1222

Weed Life Cycles

There are four basic weed life cycles: winter annual, summer annual, biennial, and perennial. Each life cycle has weak links that can be exploited in control programs. Seed-propagated weeds can be managed by preventing germination or survival of young seedlings. Perennial and biennial weeds are generally more difficult to control because they have vegetative structures that are persistent and more resilient, making these species resistant to mechanical and chemical measures. Perennial weeds in particular have varied means of reproduction that must be considered when developing management plans. In all cases, effective weed management includes preventing reproduction by removing flowers before they can set seed.

Annual weeds germinate from seeds, grow, produce seeds, and die in one season. There are two types of annual weeds. Winter annuals, such as annual bluegrass, chickweed, and henbit, germinate in the fall or early spring when soil temperatures are cool, then flower and die in late spring or summer (Table 6–2). Summer annuals, such as crabgrass, spurge, and pigweed, germinate when the soil warms in the spring and summer, then set seed and die in late summer or fall (Table 6–2). As with any rule, exceptions occur. For example, horseweed is a winter annual that can germinate in the fall or the spring. It then grows through the summer and produces seeds in mid-to-late summer. In shady or irrigated landscapes or in cooler mountain regions, soil temperatures stay cool, allowing some winter annual weeds (such as chickweed) to germinate and grow during summer.

Weed management through the year

Winter

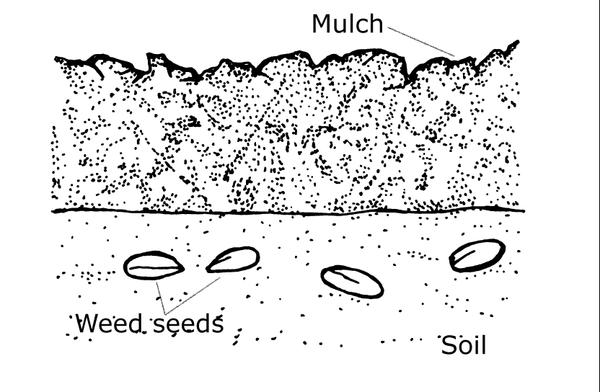

- Top-dress mulch in planting beds. Mulch helps smother weeds that germinate in the spring (Figure 6–2). Do not be tempted to use mulch excessively. The mulch layer should be 3 to 4 inches deep. Do not pile up mulch around the base of trees or shrubs.

Spring

- In early spring before seeds germinate, a preemergence herbicide could be applied. This will stop seeds of desired plants as well as weed seeds from germinating. Therefore, preemergence herbicides are best used in established lawns or planting beds where no desired plants will be sprouted from seed.

- Waiting for a flush of weeds to germinate and then controlling them with minimal soil disturbance can be an effective way to suppress weed populations. Emerged weeds can be burned by a flame weeder or an herbicide (natural or synthetic) applied before planting with desired seeds or plants. With minimum soil disturbance, the amount of new weed germination is reduced. This method is often referred to as a “stale seedbed” technique.

- Hand-pulling weeds when they are small (Figure 6–3) is not only easier but removes them before they have had a chance to produce reproductive structures (flowers and seeds).

Summer

- For fallow planting beds, solarization by using clear plastic is an option when temperatures are high (Figure 6–4). Solarization kills small seeds near the soil surface but does not affect weed seeds deeper in the soil and does not control perennial weeds.

- Continuously mow and prune the foliage. This reduces the leaf surface area that can produce food for underground storage and also removes reproductive parts (flowers and seeds).

- Hand-pull or kill weeds before they flower.

Fall

- Hand-pull weeds so their storage organs are not left in the ground over winter.

- In early fall before seeds germinate, a preemergence herbicide could be applied if winter weeds were prevalent the previous spring. This stops all seeds from germinating, so do not use this strategy in beds where you will be planting desirable plants from seed. This strategy is best used in established lawns or planting beds.

- If chemical treatment is deemed necessary to control perennial weeds, early fall is the optimal time of year to control many weeds with systemic herbicides. This ensures systemic herbicides are translocated to the storage areas of the plant as temperatures cool and plants get ready for winter.

Biennial weeds germinate from seed and produce a cluster (rosette) of leaves near the soil surface during the first year of growth. During the second year, biennial weeds flower, produce seeds, and die. Examples of biennial weeds include Queen Anne's lace (Daucus carota) and bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare). Biennial weeds are best managed in the early growing stage of the first year.

Perennial weeds grow for many years, producing seeds each year. Perennial weeds that reproduce exclusively by seed are called "simple perennials." Examples include dandelion, plantain, dogfennel, and curly dock. Simple perennials usually die back to the ground during the winter and resprout from the hardy crown or root system in the spring. Many other perennials also have vegetative reproductive organs: tubers, bulbs, or stolons. These perennials are often referred to as tuberous, bulbous, stoloniferous, or rhizomatous, respectively. Woody shrubs and vines are also perennials but are usually categorized separately as “woody weeds.”

The growth of perennial weeds is influenced by climate and season. As days shorten and nights get cooler in late summer or fall, food reserves move to the underground and overwintering reproductive plant parts. Production of tubers or bulbs is often seasonal. Time any management procedures to reduce the production of overwintering reproductive plant parts and to attack the weed at its most susceptible growth stages. For example, chemical control of perennials is often more effective in early fall, when stored food is moved to the root system, carrying with it systemic herbicides. Early-season growth of perennial weeds is rapid—neither chemical nor mechanical controls are very effective. However, repeated mowing or pruning of the foliage during summer removes flowers before they can set seed, removes leaves and thus reduces photosynthesis, and causes the plant to draw on stored resources to regrow, reducing the amount of food available for production of reproductive plant parts.

Figure 6–2. A 3- to 4-inch layer of mulch will help reduce weeds in planting beds.

Emily May, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 6–3. Hand-pulling weeds before they have flowered or set fruit will help disrupt their life cycle.

Tony Fischer, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 6–4. If temperatures are high enough, solarizing the soil with clear plastic will kill some weed seeds in the top few inches of soil.

Chris Alberti CC BY 2.0

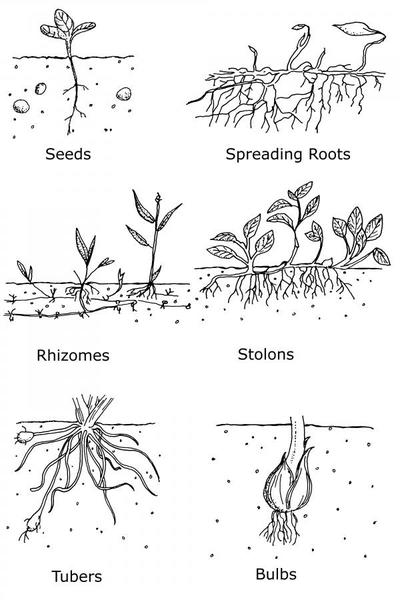

How Do Weeds Spread and Propagate?

Almost all weeds reproduce by seed. Some perennial weeds may also reproduce and spread vegetatively by creeping stems or roots, bulbs, corms, or tubers (Figure 6–5). Seeds may germinate shortly after being shed or may have mechanisms to prevent germination until conditions (sunlight, water, and temperature) are conducive to germination and growth. This quiescent state is referred to as dormancy. For example, seeds of many summer weeds require some cold temperatures before they will germinate. Cold keeps the seeds dormant until after winter, preventing them from germinating only to be killed by winter frosts prior to completing their life cycle and producing more seeds. Dormancy is a useful adaptation for survival because delaying germination until spring gives the new plants the best chance to grow, flower, and reproduce.

Weed seeds can be blown into a landscape by wind, washed in by rain runoff, or deposited in animal feces. Weed seeds can be carried in on clothing, shoes, or tools, or brought in by gardening activities such as cultivation, mowing, or adding topsoil or compost. And weed seeds can be in the root balls of purchased plants (Figure 6–6). Additionally, many common landscape weeds have means of self-dispersal. Yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis grandis), for example, has evolved a mechanism to forcefully expel its seeds up to 12 feet from the plant. Once introduced to a site, weeds can spread rapidly, and they are remarkably persistent. Pigweed and ragweed seeds can germinate after remaining in the soil for 40 years or more; mustard and knotweed seeds 50 years or more; and evening primrose, curly dock, and common mullein for 70 years or more. Each time the soil is cultivated, dormant seeds are brought to the surface where sunlight stimulates their germination. As a result, it can take years to reduce the weed seed "reserve" already existing in the soil.

Table 6–2. Some common annual, biennial, and perennial weeds.

| Lawns | Gardens | Ornamentals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer Annuals | |||

| Broadleaves – Dicots | Black medic, chamberbitter, lespedeza, prostrate knotweed, spurge | Cocklebur, lambsquarters, pigweed, prostrate knotweed, prostrate spurge, purslane, ragweed | Carpetweed, chamberbitter, mulberry weed, sida, spurge, Virginia copperleaf |

| Grasses – Monocots | Crabgrass, goosegrass, Japanese stiltgrass | Crabgrass, foxtail, goosegrass | Crabgrass, goosegrass, Japanese stiltgrass |

| Winter Annuals | |||

| Broadleaves – Dicots | Asiatic hawksbeard, bittercress, chickweed, henbit, horseweed, lawn burweed, speedwell, vetch | Chickweed, henbit, sowthistle, vetch | Asiatic hawksbeard, bittercress, Carolina geranium, chickweed, common groundsel, henbit, horseweed, shepherd's purse, sowthistle, speedwell, vetch |

| Grasses – Monocots | Annual bluegrass, annual ryegrass | Annual bluegrass | Annual bluegrass |

| Biennials | |||

| Broadleaves – Dicots | Wild carrot | Bull thistle, musk thistle | Bull thistle, musk thistle |

| Perennials | |||

| Simple | Aster, curly dock, dandelion, dogfennel, plantain, Virginia buttonweed, wild violet | Curly dock | Dandelion, dogfennel, pokeweed, Virginia buttonweed, wild violet |

| Creeping Broadleaves – Dicots | Dollarweeda, ground ivy, white clover, woodsorrel | Woodsorrel | Dollarweeda, hedge bindweed, mugwort, white clover, woodsorrel |

| Creeping Grasses – Monocots | Bermudagrass, nimblewill | Bermudagrass, johnsongrass | Bamboo, bermudagrass |

| Tubers | Florida betony, nutsedge | Florida betony, nutsedge | Florida betony, nutsedge |

| Bulbs | Wild garlic, wild onion | Wild garlic, wild onion | Wild garlic, wild onion |

| Woody | Japanese honeysuckle, poison ivy | English ivy, Japanese honeysuckle, poison ivy, smilax, wisteria | |

| a Sandhills – coastal plain | |||

Figure 6–6. Weeds can hide in rootballs of purchased plants. This sapling has a thistle and some grass growing in the pot.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Weed Ecology

Every plant has a function and niche in biological ecosystems. Plants we call “weeds” are part of the natural growth process that reclaims an open area. Open areas become populated by annual grasses and broadleaf plant species, followed by perennial grasses and biennial and perennial broadleaf species, then brambles and vines, and eventually trees. This succession in plant communities also occurs in residential gardens and lawns. Whenever a garden is cultivated, the site is essentially disturbed, which allows natural succession processes to start over again and again. We also create opportunities for undesirable species to become established when we move plants from one environment to another or when we disturb the plant community or the soil.

Weeds, like any other plant, require light, moisture, nutrients, and a suitable substrate for growth. So, what makes weeds so “weedy?” Weed species have developed a variety of ways to outcompete other plants for resources, including light, water, nutrients, and physical space. Because weeds can reproduce vigorously, and access and use available resources efficiently, weeds outcompete other plants.

One trait that allows weedy plants to be so successful is their astonishing ability to reproduce. For example, nutsedge tubers planted one every square foot on an acre of land can produce over 3 million plants and 4 million tubers in one season. Weeds can also produce a tremendous number of seeds (Table 6–3). The top inch of soil in an acre contains an estimated 3 million weed seeds. In addition to sexually reproducing by seeds, many weeds reproduce asexually via tubers, corms, bulbs, and stem and leaf rooting.

Table 6–3. Number of seeds produced by select weeds.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Approximate Number of Seeds Produced per Plant |

|---|---|---|

| Sandbur | Cenchrus longispinus | 1,110 |

| Black mustard | Brassica nigra | 13,400 |

| Curly dock | Rumex crispus | 40,000 |

| Common lambsquarters | Chenopodium album | 72,000 |

| Palmer's pigweed | Amaranthus palmeri | 117,000 |

| Evening primose | Oenothera biennis | 118,000 |

Table 6–4. Using weeds as clues.

| Condition | Weeds | |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Acidic (pH < 5) | Broomsedge, Carolina geranium, red sorrel |

| Appear pale and stunted: chickweed, dandelion, redroot pigweed, wild mustard | ||

| Slightly acid (pH 5.2) | Acceptable to most weeds, including jimsonweed and morning glory | |

| pH 5.8 – 6.0 | Appear lush and green: chickweed, dandelion, redroot pigweed, wild mustard | |

| Alkaline (pH > 7) | Buckhorn plantain, clover | |

| Soil structure | Compacted soil | Annual bluegrass, annual lespedeza, annual sedge, broadleaf plantain, corn speedwell, goosegrass, prostrate knotweed, prostrate spurge |

| Soil moisture | Moist soil | Alligatorweed, annual bluegrass, liverwort, moneywort, moss, pearlwort, rushes, sedges |

| Dry soil | Annual lespedeza, birdsfoot trefoil, black medic, goosegrass, bracted plantain, prostrate knotweed, spotted spurge, yellow woodsorrel | |

| Management | Infrequent mowing | Biennial and perennial weeds, such as aster, brambles, chicory, dogfennel, goldenrod, thistle, and wild carrot |

| Mowing too low | Annual bluegrass, chickweed, crabgrass, goosegrass | |

| Fall cultivation of the soil | Winter annual weeds, such as henbit, horseweed, and pepperweed |

Many weeds use the available resources more efficiently than other (often more desirable) plants. Weedy plants may germinate more rapidly than desirable species (think about those pesky weeds coming up in the garden before the squash germinated). Fast germination gives weeds a jump-start on growing leaves that then block slower plants from sunlight. Similarly, the root systems of some weed species are quicker to claim space in the soil. Other weed species grow more rapidly than surrounding vegetation, such as some pigweeds that grow at twice the rate of most garden plants. Weedy vines grow over the tops of more desirable plants, capturing all of the available sunlight.

Many weeds are better adapted to grow under adverse conditions, such as compacted, saturated, or nutrient-poor soils. Consequently, the presence of certain weeds may be used as an indicator of soil or management problems that need to be addressed. For example, some weeds are opportunistic, establishing in the worn or thin spots in a lawn. Be cautious, however, of making quick assumptions. Just because red sorrel is often associated with acidic soil does not automatically mean the soil it is growing in is acidic. Red sorrel can survive in very alkaline soils as well.

Weeds as Clues:

The type of weeds growing in an area can help you to identify soil conditions. Weeds can also offer clues that point to poor management of a garden or lawn (Table 6–4).

Weed Identification

While weed control by hand or by mechanical or cultural methods can be accomplished without knowing the name of a weed, it is still useful to identify the weeds because some are actually spread by cultivation rather than discouraged by it. Where herbicides are used, correct identification of a weed becomes even more critical because no herbicide kills all plants. Even nonselective herbicides have varying degrees of effectiveness on weeds. Comparing a weed to a photograph is the easiest way to identify an unknown weed. Remember that weeds can appear to be different from a picture when the weed has been mowed or has been growing under less than ideal conditions (such as shade or moisture stress).

Identifying unknown weeds is easiest when plants are in flower. But by the time plants are flowering, the damage from weed competition has already occurred. Fortunately, most weed books (see Further Reading section) also include vegetative characteristics, photographs, and keys to aid in identification. When trying to identify an unknown weed, look for unique characteristics—such as thorns or spines, square or winged stems, compound leaves, whorled leaves, and milky sap—that can often help narrow the search.

Monocot vs. Dicot

Weeds can be separated by species into broad categories based on the number of cotyledons (seed leaves). Seedlings have either one or two cotyledons, and plants are termed monocots (one cotyledon) and dicots (two cotyledons). Read more about what defines a monocot or dicot plant in “Botany,” chapter 3.

Monocot Weeds—Monocots typically have long, narrow leaf blades with parallel veins. Grasses, onions, garlics, sedges, rushes, lilies, irises, and daylilies are all monocots. For management purposes and because they can look very similar, it is important to differentiate between grasses, sedges, and rushes.

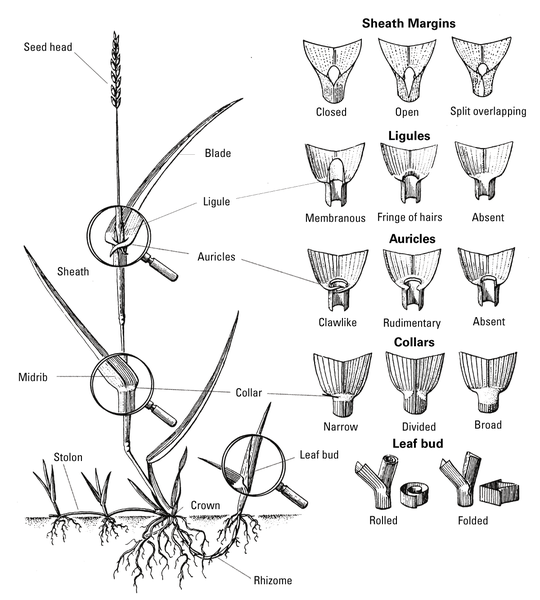

Grasses have rounded or flattened stems. Leaves are generally narrow and upright with parallel veins. Grasses have fibrous root systems, but may also produce rhizomes or stolons for reproduction. The growing point of a seedling grass is sheathed and located at or below the soil surface, protecting plants from such control measures as mowing, flame weeders, and herbicides. Examples include crabgrass (Figure 6–7), goosegrass, and dallisgrass. The most reliable way to identify grasses is by their floral characteristics. Most weedy grasses, however, can be identified with relative ease before flowering. Vegetative identification of unknown grasses relies on a few structures: leaf bud (folded or rolled), ligule (absent, hairy, or membranous), auricles (absent or present), hairs on the leaf blade or sheath and growth habit (clump-type or spreading by stolons or rhizomes) (Figure 6–8). The TurfFiles website at NC State contains an online key to help identify weeds and grasses, as well as weed profiles with images, descriptions, and management recommendations.

Sedges (Figure 6–9) and rushes are also monocots. Sedges are not grasses or broadleaf plants but are sometimes listed with grasses on the pesticide label. They have triangular, solid stems without nodes, and have parallelveined leaves that occur in threes. The perennial sedges—purple nutsedge, yellow nutsedge, and kyllinga—are particularly difficult to control.

Yellow nutsedge is the most commonly encountered sedge. It grows in nearly all crops and landscape settings; has grasslike, glossy, light-green leaves; and has yellow to tan seed heads; it spreads by rhizomes and produces tubers at the tips of rhizomes. Purple nutsedge is usually smaller and deeper green than yellow nutsedge, has reddish-purple seed heads, and produces "chains" of tubers on rhizomes. One of the easiest ways to distinguish between yellow and purple nutsedge is to look at the leaf tip. Yellow nutsedge has a very sharp, needlelike point at the leaf tip. The leaf tip of purple nutsedge is boatshaped and resembles that of bluegrass. Green kyllinga is much shorter than nutsedges, has finer leaf blades, and spreads by rhizomes that do not produce tubers. The seed head of kyllinga is globe- or cylinder-shaped, in contrast to the branched seed heads of nutsedges. Sedges are particularly important to identify because many herbicides and cultural procedures that are effective on grassy weeds do not control sedges. Additionally, sedges differ in their susceptibility to many herbicides.

Rushes have rounded, hollow stems (Figure 6–10), and their leaf blades are round in cross section (grass and sedge leaf blades are flat). The presence of large populations of rushes usually indicates drainage problems resulting in wet soil.

Dicot Weeds—Broadleaf weeds, or dicots, are a highly variable group, but sometimes they have brightly colored, showy flowers. As they emerge, dicot seedlings have two seed leaves. Leaves are diverse but generally broad with netted veins. Broadleaf weeds may have a taproot or a coarse, branched root system. All broadleaf plants have exposed growing points at the end of each stem and in each leaf axis. Perennial broadleaf weeds may also have growing points (that can produce new shoots) on roots and stems below the soil surface. Because there is much diversity among broadleaf weeds, accurate identification is necessary to select appropriate control procedures.

Some vegetative characteristics useful in identifying broadleaf weeds include growth habit (Figure 6–11), leaf orientation (opposite, alternate, or whorled), simple versus compound leaves, overall leaf shape, leaf margins (toothed, entire, lobed, or deeply cut), petiole length, and hairs on leaves or other plant parts. Drawings of leaf margins and orientation are provided in “Botany,” chapter 3, of this handbook.

Weed identification references are listed in the "For More Information" section at the end of this chapter.

Figure 6–7. Crabgrass is a monocot with a fibrous root system and long narrow leaf blades with parallel veins.

Harry Rose, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 6–9. A sedge. Insets showing the triangular stems and parallel veins.

Forest and Kim Starr, Jerry Kikhurt, and John Tan, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 6–10. This slender rush (Eleocharis equisetina) has rounded hollow stems.

Mcleay Grass Man, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 6–11. Growth habit can be a useful characteristic in identifying weeds. This spurge (left) growing along the ground, is an example of prostrate growth form. The thistle (right) is an example of an erect weed.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Weed Management: The Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Approach

Weed management consists of limiting weed infestations so that other plants can grow efficiently. Eradication is the elimination of weeds, weed parts, and weed seeds in a particular area. Eradication of all weeds is a nearly impossible goal (even fumigation does not control all weeds). For certain species that do not have long seed dormancy, eradication in a small area is possible. For the majority of weeds, however, an integrated management approach—with a goal of managing rather than eradicating weeds—is most appropriate. Integrated weed management uses one or more methods to achieve the maximum control with minimum inputs and as few adverse environmental effects as possible.

Cultural Management

Cultural methods limit the introduction, establishment, reproduction, survival, and spread of specific weed species into areas not currently infested. Cultural methods of weed management in the landscape include cultivating plants adapted to the site conditions; installing transplants rather than seeds; optimizing plant health through best management practices for plant spacing, watering, fertilizing, use of cover crops and compost; avoiding or containing potentially weedy plants; and sanitation.

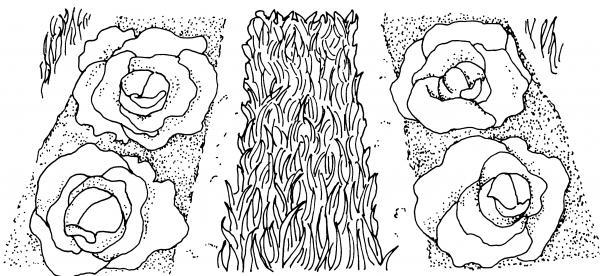

Give desirable plants a competitive advantage over weeds by providing the best possible growing conditions. Use adapted plants and cultivars, maintain adequate soil fertility, plant at the proper date, and seed or plant at the correct depth and rate. Transplants have a greater competitive edge over weeds than plants started from seeds. When using seeds, however, a uniform, well-prepared seedbed results in quick establishment, enabling desirable plants to better compete with weeds. Plant-spacing techniques can also reduce weeds. For example, if flowers are planted close enough that they grow to touch the adjoining plant, weeds have less room and light to grow. Vegetables can be planted in wide beds or multiple rows instead of single rows (Figure 6–12); this planting strategy shades more of the soil surface, thus reducing weed seed germination and helping plants compete more effectively with emerged weeds. If greater than 80% of the soil surface is shaded, weeds seldom become a problem.

Drip or trickle irrigation discourages weed growth because these methods place water only near desired plants, not in other spaces where weeds might grow. Fertilizer placed in bands near desired plants instead of broadcast widely helps the desired plants grow without promoting weeds. A cover crop like clover, vetch, or annual ryegrass between garden rows (Figure 6–13) helps reduce weed seed germination and competes with weeds that do germinate. Cover crops planted when an area is not in production also limit weed growth.

Proper composting procedures, which include reaching a temperature of 140°F and turning the pile often, kill most weed seeds and vegetative structures. The longer the pile remains at 140°F, the more weed seeds will be killed. Always inspect composts and mulches that have been stockpiled outdoors; the presence of weeds, seeds, or material that has not decomposed is a sign that the compost pile has not been properly maintained.

Weed Disposal

Weeds can be disposed of in a variety of ways. If they are dead (left in hot sun to dry) and do not contain weed seeds, they can be used as mulch around trees and shrubs. Nutsedge, bermudagrass, quackgrass, and Canadian thistle do not lose their viability until their moisture content drops below 20%. Landscape debris with weed seeds should not be used as mulch or put in a compost pile unless the compost reaches a temperature of 140°F to 160°F. The longer the pile remains at this temperature, the more likely it is that weed seeds will be destroyed. If weeds are added to compost piles, turn the pile frequently to disturb and kill any weed seedlings. Properly composted landscape debris are not be a source of weeds. But if the debris is not fully composted, many weeds can be introduced to garden or landscape beds.

Pruning certain weeds can help limit their spread. Some ornamental plants can become invasive weeds if allowed to grow unchecked. Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), for example, is a perennial woody vine that has beautiful flowers but also an ability to self-seed. To limit its spread, prune off all of the green seed pods before they mature and produce seeds. Tansy, an herb, is useful for attracting beneficial insects but can be invasive. Cut the plant back after it flowers but before it produces seed. Many other self-seeding herbaceous perennials need to be cut back before producing and shedding seeds. Remove and destroy seed heads to prevent these ornamental plants from becoming weeds in another part of the garden.

Avoid planting potentially invasive plants, or install some type of control. For example, mints spread (by rhizomes) several feet per year and are easier to manage if planted in containers. If morningglories are planted, locate them away from the vegetable garden or flower beds. Jerusalem artichokes should be planted only in an isolated area, with precautions taken to prevent the spread of roots, rhizomes, and tubers. Tilling the area spreads the underground roots. Some types of bamboo are also weedy plants and are almost impossible to contain. Flowers that naturally reseed can sometimes become weeds in landscape beds. Use such plants only in areas where self-seeding is desirable, or remove spent flowers before seedpods form.

On-site sanitation is another effective cultural control method. Clean equipment after each use because weed seeds can be moved on rototillers and mowers.

Dandelions

Dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) get a bad rap. Their image is featured on many herbicide labels, and homeowners go to great lengths to eradicate them. Dandelions thrive in sunny environments and can be found in the United States and Europe. Their leaves are long and toothed, they produce taproots that have light-colored flesh, and their yellow flowers are actually a composite of many ray flowers. Dandelions produce seeds that are attached to a tiny fluff that creates the iconic “puff ball” familiar to children everywhere. The dispersal of these seeds is one of the great milestones of childhood. Dandelions have many positive features, including these:

- As one of the first plants to bloom in the spring, the dandelion provides nectar and pollen to honeybees and other beneficial insects

- Every part of the plant is edible. Roots are used to make a coffee substitute. Tender, highly nutritious leaves can be sautéed and eaten like spinach. Flowers can be added to salads or used to make wine. Their roots can break up compact soils.

Mechanical Management

Mechanical management is used to kill weeds directly or to make the environment unsuitable for them. Mechanical methods include selectively excluding weeds, creating barriers, and such practices as hoeing, cultivating, mowing, and pruning. Mechanical methods that are not as effective include hand-weeding, covering, and solarizing undesirable plants.

Purchase weed-free seeds and plants (or at least as weed-free as possible). State and federal laws regulate the presence of certain weed species in crop seeds. Information about the kind and percentage of weed seeds is required by law to be listed on the seed packet label. Also, check container-grown and balled-and-burlapped plants for weeds before purchasing or planting; pay particular attention to perennial weeds such as nutsedge, bindweed, and bermudagrass.

Maintain weed-free borders, including underground barriers, to prevent underground encroachment by perennial weeds. Seeds from weeds in a vacant lot or along a fence row or ditch bank can be blown or washed into a landscape, so mow the weeds before they go to seed.

Mulching, another type of barrier, is by far the most common and reliable tool for preventing annual weed emergence in home landscapes. Mulch can prevent light from reaching weed seeds and thus prevent germination (Figure 6–14). In addition, weeds that do germinate under mulch may die because they do not have enough stored energy in their seeds to enable them to grow through 3 inches of mulch to reach sunlight and produce leaves. Newspapers, cardboard, bark, wood chips, shredded leaves, and pine needles are common mulching materials. Be aware that synthetic mulching materials like plastic and geotextile fabrics can become an unattractive maintenance problem as they degrade (Figure 6–15). In addition, as a layer of organic material builds up on top of these materials, weed seeds can germinate on top of the barrier and can create holes. Be careful not to introduce seeds or weed plant parts with mulch. Many mulching materials have not been completely composted and may contain weed propagules. Free sources of mulch are more likely to contain weed seeds than mulch purchased from certified suppliers. Mulches do not control creeping perennial weeds and may even enhance their growth.

Hand-pulling weeds as they appear is an effective, but only temporary, way of controlling annual weeds. Minimize soil disturbance when hand-weeding. Remember that each time the soil is disturbed, new weed seeds are brought to the soil surface to germinate. Weeds are easier to pull when the soil is moist, so try to pull them after a rain or irrigation. Pulling is less effective and more difficult for creeping perennial weeds because it is usually impossible to pull out all the underground reproductive structures.Hoeing should be done when the weeds are tiny. Hoe three to four days after a rain. Weed seeds will be swollen and ready to germinate or will already be coming up. A shallow hoeing at this time dries out the soil surface and prevents weeds from becoming established.

Lightly scraping the soil surface is the best method to control small weeds. The hoe cuts weeds just below the soil surface and brings few or no weed seeds to the surface. Many people end up with more weeds after they hoe than before they started because they use the hoe to dig rather than to skim the soil, and thus bring many more weed seeds to the surface than they killed.

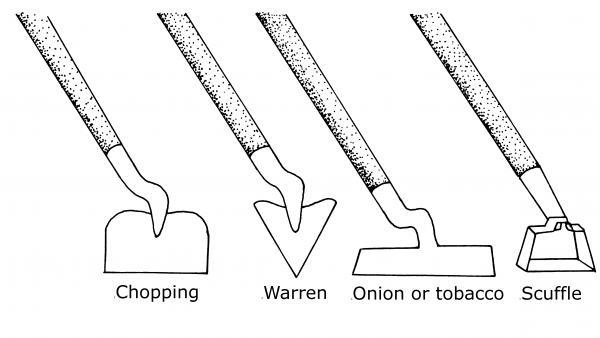

The kind of hoe selected affects the success rate in controlling weeds. The blade of a chopping hoe, for instance, tends to dig holes rather than sliding across the soil surface. Soil builds up behind the blade and moves weed seeds to the soil surface. A chopping hoe may be the only practical tool if the soil is rocky. A Warren hoe is ideal for making shallow trenches for planting but is poorly designed for severing weeds. The best hoes (Figure 6–16) for weeding are the scuffle hoe and the onion hoe (also called the tobacco hoe). These hoes allow scraping of the soil surface, and, if held at the right angle, cause the soil to flow over the hoe.

Rototillers can be used to destroy small weeds in row middles. Set the rototiller depth to about 1 inch, otherwise weeds may be transplanted rather than eliminated. Because tilling exposes seeds to sunlight and stimulates germination, be ready to manage the seedling weeds that emerge shortly after tillage.

Table 6–5. The difference between contact and systemic, selective and nonselective herbicides.

| Contact | Systemic | |

|---|---|---|

| Selective | Rapid action, visible within hours | Takes days or weeks to translocate |

| Affects only the area where applied | Affects the entire plant | |

| May require repeat applications | Affects only certain types of plants | |

| Affects only certain types of plants | Apply when plants are actively growing | |

| Works best when plants are not stressed | ||

| Nonselective | Rapid action, visible within hours | Takes days or weeks to translocate |

| Affects only the area where applied | Affects the entire plant | |

| May require repeat applications | Affects all plants | |

| Affects all plants | Apply when plants are actively growing | |

| Works best when plants are not stressed |

Another option is to till the seedbed several weeks before planting and allow weeds to germinate. Use a nonselective herbicide or flame weeder to kill the emerged weeds before planting the desired plants. After killing any weeds, avoid disturbing the soil to prevent weed seeds from germinating. This is often referred to as a "stale seedbed" technique.

Tilling is rarely effective on creeping perennial weeds and can make them worse by cutting and spreading the roots, rhizomes, or stolons. But weeds such as bermudagrass, johnsongrass, or goldenrod can be reduced by tilling during the winter and exposing the underground reproductive structures to freezing temperatures. Nutsedge can also be reduced by tilling and leaving the tubers exposed during the month of August when new tubers are normally formed.

Some gardeners cover small areas with shingles or boards in hopes of weakening weeds, but this is not an effective or recommended control method. Likewise, soil solarization, the process of harnessing the sun's energy to heat the soil, is not recommended. Solarization can heat the soil enough to control some disease organisms. But in North Carolina, it usually does not produce temperatures high enough to control weeds effectively.

Leaves are the food factories of plants. Through the process of photosynthesis, leaves create energy from sunlight. Removing leaf tissue requires the plant to use up stored reserves and can eventually starve the plant to death. Mowing, one way of removing leaf tissue, can suppress many erect weeds, reduce the food reserve of many perennial weeds, and reduce seed production in many others. However, most grassy weeds, prostrate annual broadleaves, and many creeping perennial weeds cannot be eliminated by mowing. Nor does mowing reduce competition from these types of weeds. In addition, mowers and string trimmers often cause severe damage to landscape plants by wounding the bark (often referred to as lawn mower blight). This damage is completely avoidable if areas around the base of trees and shrubs are mulched and weeded by hand.

Biological Management

Biological weed management relies on the use of beneficial living organisms, such as insects, nematodes, bacteria, fungi, or animals, to manage weeds. A benefit to using biological management versus broad-spectrum herbicides is its relative safety and low impact on the environment.

Weeds can become invasive in new environments where they have no natural predators, but weeds often have natural enemies that keep their populations in check in their place of origin. Scientists must carefully weigh the benefits and possible problems of introducing biological management measures to a new environment. Not many biological weed management options are readily available to a home gardener. Using goats to eat English ivy, kudzu, blackberries, and other weeds is one example.

Chemical Management

Chemical management of weeds relies on the use of herbicides. In IPM, herbicides are used only when needed, and the type of herbicide, timing, and placement of application are optimized to maximize benefit and minimize possible harm to people and the environment. Herbicides are used in combination with other IPM approaches for effective, long-term management.

Herbicides are chemicals used to control, suppress, or kill plants by interrupting normal growth processes. One of the greatest challenges of using herbicides is choosing the best one for the specific weed and site. Several factors affect this decision, including the weed and desired plant species, the season, weed growth stage, soil type, proximity of susceptible species, application method (spray or granular), cost, and potential environmental risks. Lists of weeds that herbicides control and which plants they can be safely used on are included in NC State Extension publications such as the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual and various crop production guides. No herbicide is safe for all horticultural plants—always read the label carefully.

To be effective, herbicides must be applied at the proper time in relation to the growth stages of the weed and the desirable plant. Newly transplanted ornamentals are often more easily injured than established plants. The length of time each herbicide will control weeds and persist in the soil depends on its mode of action, rate of application, and the soil type.

Herbicide Safety Tips

Keep new or unused herbicides in their original containers and store away from children. Do not allow herbicides to contact the skin or eyes. Change clothes and wash skin thoroughly after spraying. Do not smoke, eat, or drink while using any herbicide. Additional information on safety, storage, and use of pesticides can be found in Appendix B.

Types of Herbicides

Herbicides may be grouped or classified based on their general mode of action, or how they are used (Table 6–5). Selective herbicides control certain plant species without seriously affecting the growth of others. Some control grasses without harming broadleaf plants; others do just the opposite. For example, some herbicides selectively control dandelions without harming tall fescue growing around them. The majority of herbicides used are selective. Nonselective herbicides control or kill green plants regardless of species, controlling or damaging almost any plant contacted by the spray. Because nonselective herbicides indiscriminately control all plants, use them only to kill plants before renovating and planting an area, as a spot treatment (avoiding contact with desirable plants), or on a driveway or sidewalk where no vegetation is the desired end result.

Herbicides may also be categorized as contact or systemic action. Contact herbicides affect only the portion of the green plant tissue that is directly contacted by the spray solution. These herbicides do not move through the vascular system of plants, do not kill the underground plant parts of perennials, and may only kill the top growth of annual weeds. Adequate spray coverage—and often repeat applications—are necessary for effective management.

Contact herbicides can be selective or nonselective. For example, there are selective contact herbicides that can control yellow nutsedge in turfgrass.

Systemic herbicides are absorbed by the foliage and translocated, or moved, into the plant's vascular system. These chemicals move to and accumulate in the plant’s active growth centers, where a chemical can block or interfere with an important growth process (such as photosynthesis or respiration). Systemic herbicides kill plants over a period of days or weeks rather than immediately. It may not be obvious, however, that anything is happening. If a systemic herbicide is applied and it frustrates the gardener because it does not appear to be working quickly enough, applying a contact herbicide on the same plant may be counterproductive. The contact herbicide, while having a dramatic visual impact, can actually serve to protect the plant by preventing the translocation of the systemic herbicide. The plant may be more likely to come back than if the contact herbicide had not been sprayed. Systemic herbicides can also be classified as selective or nonselective. Selectivity results from the ability of some plants to deactivate or not absorb the herbicides or from a plant’s inherent insensitivity to the herbicide. Selective systemic herbicides are most effective when applied during times of active vegetative growth when the poison is most effectively translocated throughout the plant.

Knowing what type of herbicide you are using is very important if you compost any vegetation that may have been sprayed. Some herbicides for broadleaf plants are persistent. If turfgrass is sprayed and then the clippings are added to a compost pile, the herbicide may not break down sufficiently in the composting process. Herbicides can also carry over in manure. If you plan to add manure to your compost, ask your supplier about any herbicides used on the grazing pastures. Those herbicides can negatively affect desirable plants when that compost containing herbicide residues is added (Figure 6–17). Read more in chapter 2, “Composting,” or see this NC State Extension publication: Herbicide Carryover in Hay, Manure, Compost, and Grass Clippings: Caution to Hay Producers, Livestock Owners, Farmers, and Home Gardeners.

Adjuvants and Surfactants

Products can be added to herbicides or pesticides that can improve their performance. Adjuvants may be included in the herbicide, or they may be separate chemicals that are added to a spray tank at the time of application. Some examples of adjuvants include suspension aids, spray buffers, drift retardants, compatibility agents, and surfactants. A surfactant is a type of adjuvant that helps enhance the herbicide’s dispersion (spreading), adhesion (sticking), and plant tissue penetration. Surfactants are often used to help herbicides penetrate a waxy cuticle or a hairy leaf surface.

Time of Application

Preemergence—Preemergence herbicides do not kill existing plants or dormant seeds, nor do they prevent germination. They do, however, kill seedlings during germination. So they must be applied to a site (lawn, garden, flower bed) before weed seeds emerge. If the weed seedling can be seen, it is too late to apply a preemergence herbicide. Preemergence herbicides are effective in controlling most annual grasses and some small-seeded broadleaf weeds. In turfgrasses and ornamentals, preemergence herbicides are applied in late summer to early fall to control winter annuals such as annual bluegrass, henbit, and common chickweed. Preemergents may also be applied in early spring (before dogwoods start blooming), to control summer annuals, such as crabgrass. Preemergence herbicides remain effective for 6 to 12 weeks (varies with the chemical). A second application may be required for season-long control.

For a list of preemergence herbicides, see the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual. Relatively few preemergence herbicides, however, are readily available to homeowners. Preemergence herbicides require rainfall or irrigation to move the herbicide into the upper 1 to 2 inches of soil. Most require ¼-inch to ½-inch of rainfall or irrigation within seven days of application to activate the herbicide. If the soil does not receive adequate water in this time frame, the herbicide will not be activated and, therefore, weed control will generally be poor.

Postemergence—Postemergence herbicides are applied directly to the foliage of emerged weeds. In contrast to preemergence herbicides, the majority of postemergence herbicides do not provide residual control; that is, they control emerged weeds only and do not prevent weeds from emerging afterwards. Most postemergence herbicides are systemic but, as previously noted, some have only contact action. Apply the herbicide until just before the point when spray runs off the plant. Any spray that drips from the leaf surface is wasted and increases the expense and the environmental impact without increasing control. Postemergence herbicides are less effective when the weed is under stress (drought, cold), has begun to seed, or has been mowed within a few days before or after application. Postemergence herbicides also require a rain-free period after application. To determine the required rain-free period, read the label for each product.

Herbicide movement within a weed is slower during cool, cloudy weather. Some postemergence herbicides are temperature sensitive. The activity of these herbicides is reduced when daily temperatures are less than 60°F for several days before treatment. High temperatures (85°F or above) cause some herbicides to volatilize and move as an invisible gas to nontargeted plants and can cause excessive burn to plants in the treated area. Some postemergence herbicides are not greatly affected by low temperatures, making them an effective product for winter annual weed control in late fall through early spring in landscape plantings. Check the label of each product before using.

Nonselective herbicides must be applied in a manner that avoids contact with desirable plants. But selective herbicides to control weedy grasses (such as crabgrass and bermudagrass) may be used as broadcast sprays over broadleaf landscape plants. These selective herbicides are most effective when grasses are less than 6 inches tall.

Factors Affecting Chemical Management

Generally, the more similar the desired plant is to the weed species (in life cycles, foliar characteristics, and herbicide susceptibilities), the more difficult or impossible selective weed management becomes. It is important to identify and exploit any differences between the weed and the desired plant.

Some factors affecting chemical management include the following:

- Growing points—Points that are sheathed or located below the soil surface are not contacted by herbicide sprays.

- Leaf shapes—Herbicides tend to run off narrow upright leaves. Broad and flat leaves tend to hold herbicide spray longer than narrow leaves.

- Wax or a thick cuticle layer on the leaf surface—Either characteristic prevents herbicides from entering the leaf. The waxy surface also tends to cause a spray solution to form droplets and run off the leaf.

- Leaf hairs—A dense layer of leaf hairs holds the herbicide droplets away from the leaf surface, whereas a thin layer causes the chemical to stay on the surface longer than normal.

- Plant's age—Young, rapidly growing plants are often more susceptible to herbicides than larger, more mature plants.

- Special properties—Some plants can deactivate herbicides and are thus less susceptible to injury.

- Growth stage—Seedlings are very susceptible to most herbicides. Plants in the vegetative and early bud stages are very susceptible to translocated herbicides. Young, rapidly growing plants are often more susceptible to herbicides than larger, more mature plants.

- Application rate and uniformity—Application errors are the primary cause of poor herbicide performance.

- Season of application—When selecting herbicides, planning when to use them, and applying them, consider the season, weed growth stage, life cycle, and time of germination (relative to herbicide application).

- Weather conditions before and after application—Preemergence herbicides must be watered-in, but too much or too little water reduces their efficacy. Conditions that are too wet or too dry reduce the effectiveness of postemergence herbicides. Also, weeds must be actively growing when postemergence herbicides are applied.

- Temperature—Air temperature can have a critical effect. Some herbicides should be applied only in cool weather. Warm temperatures make some chemicals more volatile and speed up the biological and physical processes that break down herbicides in the soil.

- Species of weed to be managed—Identify the weed to select the most appropriate herbicide. Some weeds may require repeat applications.

- Soil type and organic matter—Organic matter, pH, and clay content may affect, for some preemergence herbicides, the dose required for adequate weed management.

- Cultivation—Disturbing the soil by cultivating deeply after applying preemergence herbicides reduces their effectiveness and can bring a new crop of weed seeds to the soil surface.

Herbicide Injury

Herbicide injury to plants can often be traced to application of the wrong herbicide for the site, improper application, or application under less than optimum conditions. Herbicides applied on windy or hot days can drift from the area where they were sprayed. Some formulations are especially volatile, and the vapors or fumes can drift to susceptible plants. Fine spray droplets (caused by high spray pressure) have a greater potential for drifting than sprays applied at low pressure. High temperatures (85°F or higher) during or immediately after herbicide application may cause some herbicides to vaporize and drift.

The possibility of root uptake of soil-applied herbicides depends on the herbicide, the type of soil, and its moisture content. Some herbicides are relatively mobile and move rapidly in sandy or porous soils.

Diagnosis of herbicide injury is often difficult at best. Injury often occurs within several days, but symptoms may take several weeks to appear. Some plants that are especially sensitive to herbicides include grapes, tomatoes, elms, sycamores, petunias, roses, apples, dogwoods, redbuds, forsythias, and honey locusts.

In general, broadleaf herbicide (synthetic auxin) injury appears as a strapping of the leaf with veins becoming parallel or close together. Twisting and distortion are usually associated with this narrowing and thickening of the leaf (Figure 6–18). With dicamba injury, there is usually more cupping and less leaf strapping. Symptoms from many residual herbicides are usually seen as chlorosis and death of the area between the veins. Other herbicides affect root growth, and the casual observer usually notices only a more generalized decline of the plants. These symptoms may appear on lower leaves before new growth occurs, or about evenly over the entire plant. For a more detailed list of injury symptoms see Table 6–6.

Several resources are available online focusing on herbicide injury symptoms in agronomic crops and a few focusing on horticultural crops and landscape plants. In addition, fact sheets are available from NC State to aid in diagnosing herbicide injury symptoms.

Diagnosing Herbicide Injury

- Do not make snap decisions. Gather all possible information before drawing conclusions.

- Consider planting details, such as date of planting, area planted, desired plant cultivar, seed treatment, spraying details (including chemical used, date of treatment, equipment used, spray pressure, total amount used, and total area sprayed), stage of desired plants and weeds at time of treatment, weather conditions (before, during, and after spraying), and soil conditions.

- Look for patterns in types of plants affected, location of damage (in rows, along edges, in low lying areas), differences between treated and untreated plants, and progression of symptoms.

- Watch for evidence of alternate causes for similar symptoms, such as nutrient deficiency, fertilizer burn, improper pH, pest damage (insect, mite, or disease), air pollution, weather (wind, frost, hail, drought, sun), root damage, or improper cultural practices.

Herbicide Use Guidelines

- Identify the desirable plants to be protected and the problem weeds to be killed.

- Select an appropriate herbicide. Information identifying which plants an herbicide may be used on and which weeds it will control is listed on the label and in the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

- Thoroughly read and understand the entire herbicide label. The label is the best reference on how to use an herbicide effectively and safely.

- Follow all directions on the label, including rate of application, instructions for mixing, time of application, application methods, interval between application and harvesting fruits or vegetables, storage and disposal of the empty herbicide container, and personal protective equipment.

- Never apply more herbicide than is recommended on the label. Applying more than the recommended amount does not improve weed control but may increase the risk of injury to desirable plants.

- Purchase and maintain proper herbicide application equipment.

- Do not use an herbicide on a plant that is not listed on the label.

- Do not use weed-and-feed lawn herbicides in other areas, such as landscape beds or vegetable gardens.

Cautions about Long-lasting Herbicides

Some herbicides contain products that remain active in the soil for years. These materials are rarely appropriate for use in urban areas and should be used only with extreme caution. Never apply them in areas where possible surface runoff may wash them into unintended areas. Do not apply them in areas where soil may contain tree or shrub roots. Tree roots often extend twice as far as the branches and may extend out beneath turf and be harmed by herbicides applied to lawns. Other herbicides have little or no persistence in the soil (see the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual for additional information).

Table 6–6. Symptoms of herbicide injury.

| Plant Part Affected | Injury Symptoms | Possible Causes and Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Entire Plant | Reduced plant growth and vigor while producing no other acute symptoms | Causes include low doses of herbicides sprayed over the top of plants when new growth is present, poor drainage, root-feeding insects, competition from weeds, low fertility, and water stress; look for untreated plants growing in similar conditions and carefully evaluate all potential causes |

| Leaves | Feathering of leaves; strap-shaped leaves | Leaf malformations are induced by translocated herbicides |

| Fiddlenecking in young growing points of plants; upward curling of older leaves | Symptoms are produced by growth-hormone herbicides | |

| Cupping of leaves | Distinct cupping (usually upward) is caused by growth-hormone herbicides; also may be caused by root uptake of ALS-inhibitor herbicides | |

| Crinkling of leaves; in grass species such as corn, leaves fail to emerge normally from the sheath and the plant remains in a stunted condition with twisted and crinkled leaves | Caused by thiocarbate herbicides | |

| Leaf rolling | Injury symptom on grasses can be caused by an herbicide but is more commonly caused by leaf-rolling arthropod pests | |

| Tip chlorosis (yellowing in the actively growing regions of plants); chlorotic areas may appear yellow, white, or pinkish | Typical of translocated herbicides | |

| Veinal chlorosis (yellowing of leaf veins) | Usually results from root uptake of herbicides | |

| lnterveinal chlorosis (yellowing of tissues between leaf veins) | Typically is caused by root uptake of herbicides but is also caused by some nutrient disorders, such as Fe deficiency | |

| Marginal chlorosis (a narrow, yellow band almost entirely around the leaf margin; sometimes called a "halo effect") | Can be caused by root or foliar uptake of herbicides | |

| Mottling (chlorosis that occurs randomly on the leaf); parts of the leaf remain green while others are chlorotic, sometimes puckered | Rarely associated with herbicide injury; sometimes preemergence herbicides applied over very young plant tissues can cause puckering and mottled leaves in susceptible species such as hydrangea, heuchera, and Euonymus alatus compacta; may also be injury from foliar nematodes | |

| White tissue; results from loss of all pigments (cartenoids and chlorophyll); tissues may be white or yellowish-white, often with pink on the leaf margins | Several herbicides labeled for use in turf may cause these symptons; some bacterial infections may mimic these symptoms | |

| Marginal necrosis (death of isolated tissues, often following chlorosis) on the leaf margins; develops on older leaves after they have exhibited a chlorotic condition | >An overdose of a herbicide can cause these symptoms | |

| Necrosis occurring in small spots scattered through the leaf | May be caused by contact herbicides | |

| Stems | Epinasty (bending and/or twisting that occurs in either the stem or petioles of plants) | Response often occurs within a few hours after exposure to growth-hormone herbicides |

| Abnormal stem elongation | Stem elongation of broadleaved plants may be enhanced (at low concentration) or inhibited (at high concentrations) by growth-hormone herbicides | |

| Stem cracking; stems become brittle and may break off in heavy winds; stems often crack near the soil line | Symptoms are typical of injury from growth-regulator herbicides | |

| Adventitious root formation | Can be caused by growth-hormone herbicides | |

| Swelling of coleoptiles, hypocotyl, and/or stem | Caused by growth-hormone herbicides; also a common result of stem girdling at the soil line (resulting in stem swelling above the soil line) | |

| Flowers | Changes in size, shape, or arrangement of various flower parts; branched flowers; multiple spikelets; some spikelets missing; flower partly or completely enclosed in the leaf; opposite instead of alternating spikelets along the rachis (axis of an inflorescence) | Usually caused by growth-hormone herbicides; delay in flowering due to herbicide injury is common |

| Fruit | Changes in size, shape, and appearance of fruit or abortion of fruit | Often associated with growth-regulator-type herbicides, spray drift or misapplication of contact-type herbicides |

| Roots | Development of primary and/or lateral roots is inhibited; thickened and shortened roots; usually leads to stunting of plants | Some herbicides are effective inhibitors of root growth; growth-hormone herbicides may cause swelling of roots in some plants |

Figure 6–15. Over time landscape plastics can degrade, become unsightly, and allow weeds to come through.

Chris Alberti CC BY 2.0

Case Study—Think IPM: Grass in a Flower Bed

No single herbicide or management method will control all weeds. However, by integrating cultural, mechanical, biological, and chemical methods into a weed management system, the goal of growing a relatively weed-free, aesthetically pleasing landscape or productive garden may be realized. Integrated weed management depends on correctly identifying the weed and understanding available weed management options.

It is September, and the goal is to eliminate grass growing in a flower bed (Figure 6–19). Review the steps of integrated pest management:

- Monitor and scout to determine pest type and population levels.

- Accurately identify host and pest.

- Consider economic or aesthetic injury thresholds. A threshold is the point at which action should be taken.

- Implement a treatment strategy using cultural, mechanical, biological, or chemical management, or a combination of these methods.

- Evaluate success of treatments.

1. Monitor and scout to determine pest type and population levels.

Where is the grass growing? In how large an area? This grass is part of the lawn, but it is growing out of bounds into an adjacent 15-foot by 20-foot iris bed.

When did you first notice grass in the iris bed? There were a few blades of grass in the iris bed last year, but this summer the grass is coming on strong. It is beginning to choke out the iris plants.

How important is this particular planting bed? These are grandmother’s irises and have high sentimental value.

2. Accurately identify host and pest.

You examine the grass and its seed head, which resembles a helicopter blade. The blades are smooth, pointed, and green. It has wiry stolons, and you see a ring of tiny hairs where the blade meets the sheath. The flowering structure has a whorl of five to seven seed heads at the top of stalk. You confirm the sample is that of bermudagrass, Cynodon dactylon.

3. Consider economic or aesthetic injury thresholds. A threshold is the point at which action should be taken.

You research bermudagrass and find it grows above and below the ground by stolons and rhizomes and it also reproduces by seed. It does well with heavy foot traffic and a hot dry climate, but it can easily become an invasive weed. It is difficult to remove when it is growing in an unwanted location. The longer you wait, the worse the problem becomes. Any piece of the stolon or rhizome that is left in the soil can produce a new plant. Most of the management strategies require removing the iris and then replanting once the bed is clear of bermudagrass.

4. Implement a treatment strategy using physical, cultural, biological, or chemical management, or a combination of these methods.

Cultural management—Mulching prevents bermudagrass seedlings from establishing but will not prevent bermudagrass from reestablishing via rhizomes or stolons left in the soil. Mulching suppresses most annual weeds, conserve water, and generally improve the growth of the iris plants.

Biological management—No recommended strategies exist.

Mechanical management—Physically removing as much of the bermudagrass from the iris bed as possible reduces the bermudagrass population. Iris rhizomes may need to be removed from the soil to achieve this. Any piece of the bermudagrass left in the soil can produce a whole new plant. Rototill the bed to break up stolons and bring rhizomes to the surface. Rake, pick up, and dispose of all plant material. This may need to be repeated several times throughout the summer. Never till the soil when it is damp or when any broken pieces of the grass that are not removed can sprout. Seeds remain viable in the soil for several years. Installing a weed barrier of landscape fabric can keep any bermudagrass shoots from emerging.

Chemical management—There are several postemergence herbicide options for bermudagrass suppression—both selective herbicides that specifically target grasses and nonselective herbicides that are broad spectrum (kill any living plant). It is best to apply a chemical when the grass is actively growing. For the most effective application, the grass should not be drought stressed or dusty and should not have been recently mowed so there is plenty of leaf surface area to absorb the chemical. A broad-spectrum systemic herbicide is translocated to the rhizomes and roots. It is best to apply a systemic herbicide in the fall when the plant is moving nutrients to its roots. Preemergence herbicides are not effective on bermudagrass from rhizomes or stolons but will control bermudagrass from seed.

Integrated Weed Management Options

Option 1. Cultural and Mechanical Management. Dig up the iris rhizomes and store them in a cool, dry place for the winter. Gently remove the soil and pieces of grass from the rhizomes to ensure the grass parts will not be transplanted elsewhere. Dig the bed to expose the grass rhizomes and stolons to winter temperatures and desiccation. In the spring, prepare the planting bed. Remove as much of the remaining grass rhizomes and stolons as possible. Remember bermudagrass rhizomes may grow 6 to 8 inches deep. Replant the iris rhizomes, and then mulch the bed to control annual weeds from seed (Figure 6–20). Consider installing a root barrier around the bed to prevent bermudagrass encroachment from the lawn. Hand-weed the bed every two weeks to remove bermudagrass before it can reestablish.

Option 2. Chemical Management. Because bermudagrass goes dormant in the fall, top-dress the bed with new mulch to improve the appearance. In spring, watch the bed carefully for bermudagrass emergence. When you see it emerge, begin treatment with a selective herbicide to control grasses. Spot spray as you see the bermudagrass emerging. Edge the bed with a contact herbicide to prevent encroachment from the adjacent lawn area.

Remember cultural, mechanical, and chemical options are not mutually exclusive. You may want to divide the iris plants. Periodic division and replanting invigorates iris plants and offers a chance to amend the soil. Control bermudagrass with a nonselective herbicide.

5. Evaluate success of treatments.

Keep a garden journal of photos, dates, and descriptions of management strategies to evaluate which are most effective. See Appendix A, “Garden Journaling,” for more information.

Figure 6–20. Use straw as a mulch to prevent bermudagrass from invading planting beds.

kenny_point, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Frequently Asked Questions

1. There are weeds in my lawn. How do I get rid of them?

A healthy lawn can outcompete many weeds. Review your watering, fertilizing, and mowing practices. Refer to “Lawns,” chapter 9, for recommendations. Be sure to properly identify the weed. Hand-weeding may be an option. Many effective herbicides are available for broadleaf weed control in lawns; these products are available in “ready to use” and concentrate formulations.

2. How do I control bamboo?

Clumping-type bamboos can be removed by digging up the plants. Creeping, spreading-type bamboos are very weedy once established and are extremely difficult to control. Begin with removing as much of the bamboo growth, rhizomes, and root system as possible. This may require the use of power equipment for large infestations. Follow-up treatments with herbicides are usually required. As shoots resprout, control can be obtained by applying a systemic herbicide to the new shoots before leaves open (when 12 to 24 inches high). Wear rubber gloves; wipe the entire shoot with a sponge dampened with herbicide. Avoid contact with desirable vegetation or the grass. Another option is to put the affected area into turf, as bamboo does not tolerate frequent mowing. If the bamboo is encroaching from an adjacent area, install a root-barrier 12 to 18 inches deep. The best way to control bamboo is not to plant it in the first place. If you desire to plant bamboo in the landscape, hedge bamboo (Bambusa multiplex) is a tall, tightly clumping bamboo species that can be grown in our area.

3. How do you kill Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) vines?

For small infestations, vines in the home landscape can be cut back to ground level in late summer. Treat the cut ends with herbicide. For thickets, cut all stems to the ground with a mower or string trimmer. Let the stems resprout, and then spot-spray the ends with a ready-to-use brush control herbicide. If mechanical vine control is impractical, you may still spray the honeysuckle with an herbicide, but remember that any other desirable species in the area will likely be injured. Note: Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), an invasive plant of the Southeast, is often confused with two native vines in our area: Carolina jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens) and coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). If you are unsure which vine is in your yard, bring a sample to your local Cooperative Extension center for identification before using chemical control.

4. How do I control kudzu?

Kudzu can be managed by grazing. In fact, some entrepreneurs have started businesses to control invasive species like kudzu with goats. Remember, do not allow goats to graze on plants that have been treated with herbicides, and do not allow goats near any prized plantings. Goats are nonselective and graze on all vegetation. However, where kudzu grows, there is usually very little else growing. Kudzu can also be managed with herbicides, but it may take several years of follow-up applications to eradicate this vine from your yard. Before applying herbicide, cut off vines at ground level, and, if possible, use a mower or string trimmer to cut patches to ground level during the growing season so that root crowns are visible. Allow vines to resprout. Then in late summer, spot-spray the ground level foliage at the root crowns with herbicide that includes a surfactant solution. If mechanical control is impractical, you can still spray the kudzu with an herbicide that includes surfactant solution. But spray carefully. Do not spray in windy conditions because these herbicides are not selective and can injure or kill any green plant tissue.

5. Can I spray a nonselective herbicide to kill weeds on my bermudagrass lawn when it is dormant?

A healthy lawn outcompetes most weeds, so one option would be to wait until spring and encourage the lawn to come out of dormancy with proper irrigation and fertilization. A second option would be to use a selective herbicide for broadleaf weeds. If your goal, however, is to kill grass weeds that are actively growing when your lawn is dormant and if it is not possible to wait, a nonselective herbicide applied at the labeled rate can be used on bermudagrass that is fully dormant. If applied at the right time and in the right concentration, a nonselective herbicide can be effective at managing many winter broadleaf and grassy weeds. The efficacy of the herbicide is much greater when temperatures rise above 60°F. The challenge lies in timing the application so the temperature is warm enough but the bermudagrass is still dormant. Some winters are very mild or have fluctuating temperatures. Under those conditions, bermudagrass never goes completely dormant. Although the application at labeled rates do not completely kill semidormant bermudagrass, it may delay spring green-up. Common bermudagrass is slightly more tolerant to herbicides than hybrid bermudagrass varieties such as ‘Tifway.’

6. Can I spray a broadleaf herbicide in my flower bed for weeds and not hurt my flowers?

The simple answer is “no.” Broadleaf herbicides target dicot plants. Many flowers are dicots, so blanket spraying flower beds for weeds is not recommended. Hand-pulling weeds is the safest option for surrounding plants, but you need to be sure to get the entire root of the weed. If hand-pulling is not an option, target specific weeds by protecting other plants. Use a can or milk jug (or other plastic container) with both ends cut off to make a “collar.” Place this collar over the weed, and spray only inside of the collar. Alternatively you can paint herbicide on the leaves of weeds with a foam applicator brush. There are often weed seeds in the soil that continue to germinate over time. By applying mulch or a preemergence herbicide, you can stop those seeds from emerging.

Further Reading

Baldwin, Ford L., and Edwin B. Smith. Weeds of Arkansas Lawns, Turf, Roadsides, Recreation Areas: A Guide to Identification. Pine Bluff, Arkansas: University Of Arkansas Division of Agriculture Cooperative Extension Service, 1981. Print. Publication MP 169.