People are increasingly aware of the importance of the bats they once persecuted. Increased pesticide use, the loss of roosting locations, degradation of some foraging resources, and the spread of white-nose syndrome has resulted in a dramatic decline in abundance of many bat species.

White-nose Syndrome (WNS) is a fungal disease that grows on the bats’ skin and has caused massive population declines in many species of bats. WNS kills bats during hibernation by causing them to awaken prematurely and burn essential winter fat stores. WNS spreads easily from bat to bat, and may also spread inadvertently by spores carried on human clothing and equipment. To help prevent further spread of WNS, people who enter mines and caves where bats live can properly decontaminate any clothing or gear after visiting sites where the fungus may occur.

North Carolina supports 17 species of bats, including four federally listed as threatened or endangered. This publication provides information about bats, their benefits, and steps to encourage bats on private lands.

The Importance of Bats

Bats serve as important pollinators of many food plants and provide useful aids for medical research, particularly for the blind, who like bats, can learn to navigate using echolocation.

Bats are the only major predator of night-flying insects, acting as a valuable natural pest control resource. Bat prey includes lacewings, cockroaches, gnats, beetles, moths, and mosquitos. A single Big Brown Bat can eat between 3,000 and 7,000 mosquitos in a night, with large populations of bats consuming thousands of tons of potentially harmful forest and agricultural pests annually.

Permanent wet areas are critical for bats because they supply water and a consistent insect supply.

| Big brown bat | Eastern Red Bat | |

| Eastern Small-footed Bat | Evening bat | |

| Gray Myotis* | Hoary Bat | |

| Indiana Myotis* | Little Brown Myotis | |

| Mexican Free-tailed Bat | Northern Long-eared Bat* | |

| Northern Yellow Bat | Rafinesque's Big-eared Bat | |

| Seminole Bat | Silver-haired Bat | |

| Southeastern Myotis | Tri-colored Bat |

|

| Virginia Big-eared Bat* | ||

| * federally listed as threatened or endangered | ||

Flying Mammals

Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. Their wings are like hands with skin stretched between modified finger bones. They are not blind, but rely on echolocation instead of their eyes for locating and capturing food at night. Bats are more closely related to primates than the rodents with which they are often compared. They have slow reproductive rates with typically only one offspring per cycle. Like all other mammals, female bats nurse their young.

Balancing Bat Habitat

Providing both foraging areas and roosting locations is essential. Bats spend over half of their lives in roosts and rely on sheltered, undisturbed sites such as caves, crevices in rocks, and tree cavities to meet their needs. In the winter months, insulated roosts are important for hibernating bats, while in late spring and early summer, roosts that can sustain daytime temperatures between 80 and 90 degrees Fahrenheit are important for raising young bats. Bats are somewhat opportunistic in their roost selection and often use man-made structures such as attics, abandoned houses, bridges, and barns where natural roosts are unavailable.

| Foraging | Roosting |

| Beaver ponds | Caves |

| Marshes | Snags |

| Streamside forests | Cavities in live trees |

| Thinned forest/woodland | Abandoned homes |

| Seasonal pools and ponds | Bridges |

| Cropland edges | Crevices in rocks |

Promoting Bat Habitat

Encourage bats on your property by creating all components of bat habitat in close proximity. Maintain and manage snags in mature woodlots to increase the availability of cavity roosts. Avoid use of insecticides. Do not disturb nesting, roosting, or hibernating bat colonies. Protect water sources such as beaver ponds, marshes, and streams, which all provide drinking water and foraging areas for bats.

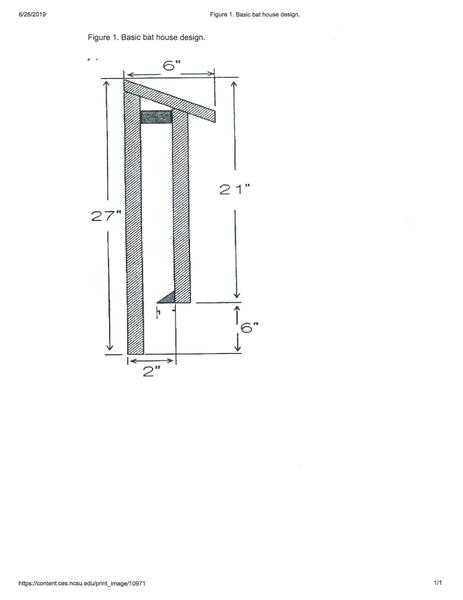

Install properly constructed artificial roosts in areas were natural roosts are scarce or absent. Solitary, foliage-roosting species such as the Hoary Bat will not use bat houses consistently as will the colonial bats, which include the Little Brown Myotis, Big Brown Bat, and Tri-colored Bat. See Figure 1 for a diagram to build effective, maintenance-free bat houses for roosting and raising young.

Construction Tips

• Use cedar, cypress, or pressure-treated pine lumber to insure durable, longer-lasting boxes.

• Use rough lumber, cut shallow grooves, or attach fine plastic or wire mesh to the inner surfaces of the box so bats can easily crawl up and into the house.

• Avoid painting or varnishing the inside of the house.

• Use a dark or medium shade of paint on the outside of the box to ensure the high temperature ranges required by both young and adult bats.

• Seal all seams with silicone caulk to waterproof houses and prevent heat and moisture losses.

Installation Tips

• Place bat boxes close to rivers, lakes, ponds, marshes, or other permanent water sources where insects are abundant.

• Mount boxes on posts made of metal or wood and away from overhanding tree limbs. Boxes mounted to trees will be less attractive to bats because the houses will be more accessible to snakes and other predators.

• Tilt houses at a 10 degree angle to help young bats stay in the box.

• Place bat houses 10 to 15 feet off the ground. Always seek assistance when using folding or extension ladders.

• Locate boxes where they will absorb maximum sunlight. Where possible, place four boxes per tree, one each facing North, South, East, and West, to allow the bats to choose the box they need.

• Install bat houses by early April. Don’t worry if bats do not begin using them immediately. A survey by Bat Conservation International (BCI) showed an approximately 60% occupancy rate for all boxes. It may take up to two years for bats to find and begin using artificial roosts.

• Inspect bat houses annually and remove any vegetation that could interfere with entry to the roost or allow predators to enter. Attach predator guards of roofing tin on the mounting post at a height of three feet to protect roosting bats from house cats, raccoons, and snakes.

References

Harvey, M.J., J.S. Altenback and T.L. Best. 1999. Bats of the United States. Arkansas Game & Fish Commission.

Johnson, C.M. and R.A. King, eds. 2018. Beneficial Forest Management Practices for WNS-affected Bats: Voluntary Guidance for Land Managers and Woodland Owners in the Eastern United States.

Tuttle, M. and D. Hensley. 1993. “The Bat House Builder’s Handbook.” Bat Conservation International, Inc., P.O. Box 162603, Austin, Texas 78716-2603

Webster, W.D., J.Parnell and W.C.Biggs, Jr. 1985. Mammals of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Working With Wildlife

North Carolina State University Extension - Forestry

Working With Wildlife Series

Publication date: April 5, 2019

Reviewed/Revised: May 28, 2024

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.