Outline

North Carolina’s Ecological Regions

Why Should Gardeners Plant Natives?

Objectives

This chapter teaches people to:

- Explain why the term “native” is of no value without specifying time and location

- Define the ecological regions of North Carolina

- Recognize the connection between native plants and native wildlife

- Appreciate the importance of native plants in an ecosystem

- Describe two principles of gardening with native plants.

- Select appropriate native plants for a given landscape.

Introduction

Landscaping with native plants empowers gardeners to care for nature and enhance the local environment while adding beauty and diversity to their homesites. By planting natives, gardeners support native pollinators and connect with the natural heritage of a region. Gardeners and the environment reap the most benefits from natives when gardeners understand key concepts related to the meaning of the words “native plant,” the value of incorporating native plants into landscapes, and principles of gardening with native plants.

What Are Native Plants?

Native plants are those species that evolved naturally in a region without human intervention. Red maple (Acer rubrum), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), and butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) are examples of the over 3,900 species of plants the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) PLANTS Database lists as native to North Carolina. These plants developed and adapted to local soil and climate conditions over thousands of years and are vital parts of local ecosystems necessary for the survival of pollinators, insects, birds, mammals, and other wildlife.

Plants are not considered native to a region within decades or even centuries after introduction. To be native, they must originate in the region and co-evolve with other species over thousands of years. As these species evolve together, they adapt to the physical environment formed by local climate and weather conditions, soil types, topography, and hydrology.

Native plants form interdependent, highly specialized relationships with other organisms that are necessary for each other’s survival. Replacing natives with plants from other regions cannot replicate the complex interactions that naturally occur.

North Carolina's Ecological Regions

Climate, geology, and evolutionary history determine the distribution of plants, animals, and other organisms in complex ways. In large areas with similar climate, ecosystems recur in predictable patterns. These patterns, known as ecological regions or ecoregions, provide the boundaries for a meaningful definition of the term “native.”

“Ecoregions of North America” was developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to provide a framework for the environmental study and conservation of the continent's ecosystems; this system also provides a useful framework for gardeners when selecting native plants.

“Ecoregions of North America” has four levels, each progressively more refined. Level III is probably the best reference for gardeners to use to define regions for selecting native plants. This level subdivides North America into 182 ecoregions and is used to define regions within which plant material can be transferred with little risk of it being poorly adapted to the new location. The four Level III ecoregions found in North Carolina align with our state’s physiographic regions as follows:

- Middle Atlantic coastal plain and Southeastern plains ecoregion (combined) align with the NC coastal plain, including the NC sandhills region.

- Piedmont ecoregion aligns with the NC piedmont.

- Blue Ridge ecoregion aligns with the NC mountains.

Level IV further subdivides each Level III ecoregion into smaller areas that more fully reflect the enormous biological and ecological diversity of our state. This level is of interest to gardeners seeking a local, specialized, frame of reference. Ecoregion maps are availabe to download from the EPA.

Selecting native plants begins with defining the ecoregion of the property to be landscaped and then identifying plants native to that ecoregion. Choosing plants native to the local region will provide the greatest benefits to wildlife and the environment.

Native Plant Terminology

Many terms describe native plants and where they occur. The term “indigenous” is synonymous with native, but neither term specifies where a plant is native. Native range describes the area over which a plant naturally occurs. Although it is convenient to refer to a plant’s native range using political boundaries, such as county or state names, soil and climate conditions determine plant distribution. It is more important to know a plant’s adaptation to the ecoregion and growing conditions than whether or not a species occurs within a specific county.

Plants limited to one region are said to be endemic to that region and often occur on sites with specialized soils and hydrology. For example, Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) is endemic to a small portion of North Carolina's and South Carolina’s coastal plain (Figure 12–1). This well-known carnivorous plant grows in nutrient-poor, highly acidic, poorly drained sandy soils. Plants with such a limited native range that are adapted to very specific growing conditions are less likely to survive in the typical landscape.

Plants with a broad native range may occur in each of North Carolina’s ecoregions, as well as in other states. For example, red maple (A. rubrum, Figure 12–2) has a native range that extends along the Atlantic seaboard and well into the center of the country. Such plants typically adapt to a variety of habitats and are more likely to survive in conditions found in residential landscapes. The USDA’s PLANTS Database is an excellent resource for determining a plant’s native range.

What Are Wildflowers?

The term wildflower is often used to describe native plants, but may also refer to naturalized plants that are not indigenous to the region. In addition, wildflower plantings and seed mixes often include species from other parts of the country or world. Don’t assume plants or seeds labeled as wildflowers are native to your region; when purchasing wildflowers, identify the species, then determine if it is native to your region.

Natural Communities

Native plants occur within natural communities, which are defined by the NC Natural Heritage Program as “distinct and reoccurring assemblages of populations of plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi naturally associated with each other and their physical environment.” Within North Carolina, 30 natural communities have been identified, each with multiple subtypes related to the dominant plant species and conditions—soil, hydrological, and geological—that shape that community. A plant’s inclusion in a natural community is not exclusive; many native plant species are components of several natural communities.

Knowing the natural communities within a region helps gardeners identify plants that will thrive in that region’s landscapes, and better match a given plant to a suitable site. One resource that gardeners can use to learn about the natural communities in their region is the Guide to the Natural Communities of North Carolina, Fourth Approximation, written by Michael Schafale. It is available from the NC Natural Heritage Program.

What is provenance?

Provenance refers to where, within a plant’s native range, seed or propagation materials, such as cuttings, were collected. For example, red maple trees (A. rubrum) grown from seed collected near Pittsboro, North Carolina, have an NC piedmont provenance. The characteristics of plants with a broad distribution can vary from one area of their range to another. Red maple trees grown from seed collected in the northern part of the red maple’s range, for example, produce fall color two to three weeks earlier than trees grown from seed collected in the southern part of its range, even when trees grown from northern seed are planted in the South.

Try to locate plants of local provenance when creating habitat or restoring disrupted natural areas. Plants sourced within the same ecoregion ensure the best possible fit with local conditions and wildlife.

Naturalized and Invasive Plants

Not all plants growing wild in a region are natives. Nonnative, or exotic, plants that reproduce and establish outside their native range are described as naturalized. According to the USDA PLANTS Database, over 1,100 species of naturalized plant species grow in North Carolina. Examples include many common weeds and wildflowers, such as chickweed (Stellaria media), white clover (Trifolium repens), Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota), and orange daylily (Hemerocallis fulva), all of which were introduced from Eurasia.

Weeds are nuisance plants that interfere with human activities, such as farming, gardening, and turf maintenance. When cultivated areas are abandoned, most common lawn and garden weeds disappear after a few years, allowing native plants and the many wildlife species that rely upon them to re-establish.

A small percentage of plants introduced to North Carolina have become exceptionally persistent and damaging. These extra-aggressive nonnative species, capable of invading natural areas and destroying ecosystems, are known as invasive species. The USDA’s National Invasive Species Information Center characterizes invasive species as adaptable, aggressive, and having a high reproductive capacity. Because they did not evolve locally, invasive species lack the natural enemies that limit aggressive spreading in their native habitat, resulting in rampant, uncontrolled population growth that can threaten the health of humans, livestock, wildlife, and ecosystems.

Invasive species are one of the greatest threats to ecosystems worldwide. Many invasive plants in the United States were originally introduced for agricultural or ornamental use. For example, kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata) was introduced to the Southeast in the 1930s for erosion control and animal fodder. Invasive plant species that were introduced as landscape plants, but have become too well-adapted to local conditions, include Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), autumn olive (Eleagnus umbellata), Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense, Figure 12–3), English ivy (Hedera helix), and Asian wisterias (Wisteria floribunda and Wisteria sinensis).

Exotic plants are most likely to become invasive in regions with soil and climate conditions similar to those of their native habitat. Plant species that are invasive in one ecoregion of the state may not be invasive in others. For example, the invasive species Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) is particularly problematic in the Blue Ridge Mountains, but not in the NC coastal plain.

One of the most important things gardeners can do to protect local ecosystems is to identify and remove invasive plants from their property and avoid planting species that have a high potential to become invasive. Resources to help gardeners and landowners in North Carolina identify and manage invasive plants are available from the NC Invasive Plant Council, NC Native Plant Society, and NC Forest Service.

Figure 12–3. Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense) is an invasive plant in North Carolina.

Melissa McMasters, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Why Should Gardeners Plant Natives?

Including native plants in the landscape helps gardeners create visually appealing outdoor spaces and build healthier local ecosystems. The key to understanding why natives are so important in our gardens lies in recognizing the essential role plants play in supporting biodiversity and the ecosystem services needed to sustain our environment.

The Need for Biodiversity

Biodiversity refers to the variety of living organisms. It can describe the number of different ecosystems or habitats within a region, the number of species within an ecosystem, as well as the genetic diversity within a species. Biodiversity sustains the natural processes that support all life on earth, known as ecosystem services. According to the Ecological Society of America, healthy ecosystems are needed to provide services that accomplish these functions:

- Pollinate crops and natural vegetation (Figure 12–4)

- Disperse seeds (Figure 12–5)

- Balance agricultural and garden pest populations

- Regulate disease-carrying organisms

- Generate soils

- Cycle and move nutrients

- Purify the air and water

- Detoxify and decompose wastes

- Contribute to climate stability

- Moderate weather extremes and their impacts including drought and floods

- Protect streams, river channels, and coastal shores from erosion (Figure 12–6)

The destruction of natural habitat is the greatest threat to biodiversity worldwide. In fast-growing regions, development often fragments remaining natural habitats into smaller pieces that are less likely to support the needed range of ecosystem services. As natural areas disappear, residential landscapes become more important sources of nourishment and habitat for the many species needed to support healthy ecosystems.

North Carolina’s population is increasing. Each year new homes and communities are constructed, removing natural habitat and native plants from local ecosystems. Many communities scarcely resemble the natural areas they replace, and nonnative turfgrasses, shrubs, and flowers often dominate residential landscapes. These plants are unable to perform the same ecological roles as the native plants they replaced. As a result, other species native to the region cannot survive, diminishing the biodiversity of the community. By restoring native plants to landscapes, gardeners help preserve biodiversity and create opportunities to interact with birds, butterflies, bees, and other species in their yards.

The Role of Plants in Ecosystems

Plants, animals, and microbes interact with nonliving elements, such as air, water, and minerals to form ecosystems. Each element—living or nonliving—is integral to the system, and changes to any component have the potential to affect all other parts of the system. This definition extends to residential landscapes, which are part of the local ecosystem. Everything that happens in a landscape, from plant selection and landscape design, to pesticide and fertilizer applications, can either help or harm the local ecosystem.

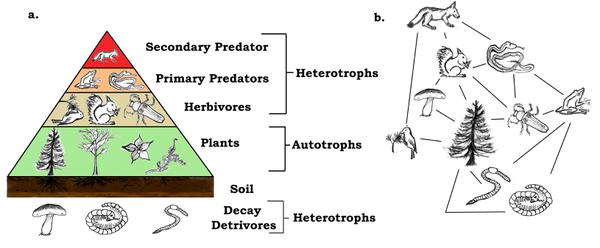

Living organisms within an ecosystem connect through a food web: a complex, overlapping series of pathways that move energy and nutrients through the ecosystem (Figure 12–7). Trophic levels describe the position an organism occupies in a food web—what the organism eats and what eats it. As one species eats another, energy moves from one trophic level to the next. Plants are the first trophic level in almost every food web on earth.

Within most food webs, plant-eating insects make up the second trophic level. A significant percentage of the world’s animals depend on insects to access the energy plants store. For example, insects are a critical food source for the survival of most bird species. Adult birds may feed on insects, seeds, and berries, but juvenile birds require a diet of insects to provide the protein for development (Figure 12–8). Large numbers of caterpillars feeding on native tree leaves are the food source that sustains the nestlings of many bird species. Just consider this: 6,000 to 10,000 caterpillars are needed to successfully raise a single nest of chickadees!

In any ecological region, the coevolution of plant and insect species over thousands of years includes plant defenses against insect predation and insect processes to counteract those defenses. In many cases, an insect’s adaptation focuses upon a limited range of closely related plants that occur within that insect’s native range. Insects that evolved to feed upon specific plant species cannot survive if those plants are not available. This is particularly true for leaf-feeding insects, such as butterfly and moth larvae (caterpillars).

Monarch butterflies are a well-known example of such specialized adaptation. The survival of monarch butterflies depends on plants in the genus Asclepias, commonly known as butterfly weed or milkweed. Monarch caterpillars cannot feed on any other plant genus; if Asclepias spp. disappear from a region, so do monarchs (Figure 12–9). This is true for other insects that rely upon specific plant species: If their host plants disappear, these insects cannot survive, which reduces the food supply for other organisms in the food web.

Gardeners play a valuable role in helping the environment by putting native plants to work in their landscapes. Landscaping with native plants sustains native insect populations, ensuring these insects are available for the birds, mammals, and other organisms that rely on insects for food. Gardeners may be reluctant to intentionally select plants for insects to feed upon, but native plants and native insects evolved together and established native plants can withstand the minor injury these insects cause. Researchers conclude that gardeners don’t even notice such damage until insects injure up to 10% of a plant’s foliage, so a few nibbled leaves are not likely to detract from the landscape’s appearance. In a balanced ecosystem, species further up the food chain eat plant-feeding insects before the insects cause serious harm.

Additional Reasons to Plant Natives

Creating an ecologically balanced landscape that attracts a multitude of birds and pollinators is not the only reason to use native plants in landscapes. Within North Carolina’s ecoregions, approximately 3,900 species of native plants have been identified—from towering, graceful trees to striking shrubs and perennial wildflowers. The selection of native plants from any of our state’s ecoregions is diverse and offers numerous varieties that are sure to enhance the beauty of all types of gardens—from more traditional, formal designs to free-form natural gardens. Whatever the style of a landscape or garden, the inclusion of native plants can contribute to its visual appeal.

Landscapes that include diverse regional flora provide a connection to the area’s natural history. Such landscapes harmonize with their natural surroundings, creating a sense of place often lost when a limited selection of exotic species that can be grown from coast-to-coast dominates landscapes.

Incorporating native plants also commemorates the gardening history of a region. Many native plants used in southern gardens since the colonial period have long horticultural histories. Examples include southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera), redbud (Cercis canadensis), cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), oakleaf hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia), and foamflower (Tiarella cordifolia).

Are hybrids and cultivars native?

Do cultivars and hybrids of native plants support ecological functions as well as their wild relatives? Should we label such cultivars and hybrids, sometimes called “nativars,” as native plants? There are no decisive answers to these complex questions.

Cultivars are varieties of a species that are selected because they have larger flowers, shorter stature, extended bloom times, different colored petals or leaves, or some other feature gardeners find desirable. For example, ‘Shamrock’ is an inkberry holly (Ilex glabra) cultivar selected because it is more compact and holds its color better in winter than the wild species.

Hybrids are the result of two closely related plants, typically from the same genus, cross-pollinating and producing a viable offspring. Hybrids inherit genes from both parents and typically exhibit traits that are intermediate of the parent species. Hybrids can occur in nature where the distribution ranges of closely related plants overlap. Vernonia × georgiana is an example of a naturally occurring hybrid between Vernonia acaulis, stemless ironweed, and Vernonia nudiflora, narrow-leaf ironweed. All species of Vernonia are highly attractive to bees, so this hybrid may also occur in gardens where these species are grown together.

Gardeners and plant breeders intentionally cross two species to create hybrids. Some common reasons landscape plants are intentionally hybridized are to develop disease-resistant strains, to create novel flower or foliage colors, and to improve growth habit or performance in nursery production systems. Many of the new coneflower (Echinacea spp.) varieties with orange, yellow, and red flowers are hybrids between purple coneflower, Echinacea purpurea, and other Echinacea species, including E. angustifolia, E. paradoxa, E. laevigata, and E. tennesseensis (Figure 12–10). Although we can bring together two species that do not have overlapping native ranges, we cannot cross species that would not naturally do so.

Cultivars or hybrids of wild species do not necessarily show diminished ecological performance. In some cases nativars are more attractive to pollinators or leaf-feeding insects than their wild parents and in others they are less so, according to Doug Tallamy’s research at the University of Delaware. Characteristics that reduce plant attractiveness to pollinators or leaf-feeding insects include:

- Having extra petals or fully double flowers. Pollen and nectar are less accessible to pollinators; pollen and nectar-bearing structures are absent in fully double flowers.

- Being sterile. Sterile plants do not produce seeds or fruits. In some plants, sterile varieties do not even produce pollen. Planting a sterile selection of a native plant reduces food resources available to pollinators and birds.

- Having purple or highly variegated leaves. Purple leaves are higher in anthocyanins than green leaves, while variegated leaves contain less chlorophyll. Both of these characteristics can deter leaf-feeding insects.

- Earlier or later blooming or fruiting times than wild species. Altered bloom or fruiting times may not be in sync with local wildlife populations.

Although nativars with these characteristics may not perform the same ecological function as wild species, they may have a place in sustainable landscapes along with noninvasive, nonnative species, when sited appropriately and used in moderation alongside species native to a region.

Figure 12–4. Squash bees (Peponapis pruinosa) are important pollinators of cucurbits such as squash, pumpkins, and gourds, and are one of many native insects that provide vital pollination services.

Ilona Loser, Wikimedia CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 12–5. A healthy ecosystem supports life forms that help disperse seeds like these cedar waxwings are doing on a juniper tree.

Del Green, Pixabay CC0

Principles of Gardening with Native Plants

Native plants still require thoughtful selection and care for long-term success. Choosing species adapted to the site conditions, preparing the soil, helping plants establish, and following ecological design principles ensures the gardener and the local ecosystem gain the most benefit from including native plants in landscapes.

Choose the Right Plant for the Site

North Carolina’s amazing diversity of natural habitats ranges from coastal dunes and saltwater marshes, flat woods and inland swamps, rolling hills and highland meadows, to steep slopes and rich mountain coves. This variety of habitats means North Carolina has one of the most diverse floras in North America, offering numerous species of beautiful native plants well-suited to landscaping. The first step in selecting the right species for the site is performing a site analysis to assess these attributes:

- Soil texture, drainage, and pH

- Intensity and timing of direct sun and shade during the growing season

- Amount of horizontal and vertical growing space

A detailed site analysis helps you choose species adapted to the site’s growing conditions. While plant tags often include sun or shade requirements, soil texture, drainage, and pH are equally important for success. Plants requiring well-drained conditions die quickly in wet areas; wetland plants may adapt to drier sites, but appreciate supplemental watering during dry spells. Choosing the right plant for the site is the most practical, economical, and sustainable approach to plant selection.

Many urban landscape conditions do not resemble natural habitats found in North Carolina. This is particularly true for parking lots and street tree plantings, which have highly disturbed soils and drainage patterns. Paved surfaces also reflect heat, creating extra stress. In planting sites surrounded by impervious surfaces, choose plants that can tolerate these harsher conditions (Figure 12–11).

Many genera native to the state include multiple species, each adapted to different growing conditions. For example, there are 16 species of Asclepias found in North Carolina—some growing in wetland habitats, and others found only in upland areas. All species are larval hosts of the monarch butterfly. The two most common landscape species, butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), are found in each of the state’s ecoregions, but grow in very different habitats. As its common name implies, swamp milkweed prefers consistently moist sites and tolerates shallow flooding; butterfly weed thrives in well-drained soils and is exceptionally drought-tolerant. Using these plants successfully and sustainably in the landscape requires matching the right species to the site.

Choose Natives Suited for Landscaping

Not all native plants are good candidates for landscaping. Some are too vigorous, producing rhizomes or stolons that quickly dominate smaller planting beds. Examples include obedient plant (Physostegia virginiana), hardy ageratum (Conoclinium coelestinum), and tall goldenrod (Solidago altissima). These plants are best reserved for large-scale plantings, such as meadows or natural areas.

Some of North Carolina’s most spectacular native plants require very specific soil and moisture conditions not found in most landscapes. This limits their usefulness as landscape plants. Examples include the beautiful, yet notoriously difficult to cultivate, pink lady’s slipper orchid (Cypripedium acaule), and the striking lady lupine (Lupinus villosus), which grows in areas of deeply sandy, extremely well-drained soil found only in the counties of the NC southern coastal plain (Figure 12–12). For most plants from very specialized habitats, it is better to admire them in the wild rather than waste resources attempting to grow them in the landscape.

To determine if a native species is a good fit for a landscape, consider these factors:

- Growth habit in relation to available space, including height, width, and if the plant is a vigorous spreader

- Adaptability to the growing conditions found in the landscape, including sun or shade exposure, soil type, and drainage

- How well the plant fits the purpose for which it is planted

- If the plant is commercially available or sustainably propagated

Prepare the Soil and Help Plants Establish

Even though native plants survive in natural areas without care, this trait does not mean the plants will be able to do the same in a yard—even when you select the right plant for the site. Construction and development alter soil conditions, and almost everyone’s landscape was a construction site at some point. Removal of organic matter and soil compaction are the two most damaging construction-related changes to natural soil conditions.

During construction, removing the top layer of soil, commonly known as the topsoil, is a typical first step. Topsoil contains more organic matter than the layers below, so removal strips away organic matter needed to support the healthy growth of plant roots and beneficial soil microbes. Heavy equipment traffic in and around the construction site compacts the soil (Figure 12–13), compressing pore spaces that allow water to infiltrate and percolate through the soil profile. This diminishes drainage and reduces soil oxygen that most plant roots and soil microbes require to survive.

Alleviating soil compaction before planting gives any plant, including native species, the best chance to thrive. Incorporating a 1-inch to 3-inch layer of compost into the soil before planting adds organic matter back to the soil, helps reduce compaction, and restores soil structure. Always test soil before planting to determine if nutrient levels and soil pH are in the appropriate range for the desired plants. If lime or nutrients are recommended, incorporate them into the soil before planting. Amend the soil over the entire planting area rather than amending individual planting holes.

As with all plants, keep newly planted natives well-watered for the first few weeks after planting, or until their roots establish into the surrounding soil. Depending on soil texture, microclimate conditions, and plant species, native plantings may or may not require additional irrigation and fertilization after planting. Plants growing in locations where buildings and hard surfaces interfere with rainfall infiltration are more likely to require additional watering after establishment.

In addition to soil test results, let plant growth and appearance be the guide to determining nutrient needs. If plants are growing at a satisfactory rate and have plenty of healthy green leaves, you do not need to fertilize. Maintaining a 2-inch to 3-inch layer of mulch around plants helps conserve soil moisture, moderates soil temperatures, prevents weeds from self-seeding, and slowly adds organic matter to the soil. In areas where deciduous trees are established, allow leaves to serve as natural mulch by leaving them in place when they fall.

Maximize Wildlife and Ecological Value

Different species of birds, pollinators, and other creatures have distinct preferences for where they nest, what they eat, and when they are active. A landscape that maximizes biodiversity and benefits the local ecosystem relies on planting a diverse mixture of species to create a variety of habitats and provide flowers, fruits, and seeds throughout the year.

Plan for diversity

Many southern landscapes are primarily composed of common nonnative plants, such as ‘Bradford’ pear (Pyrus calleryana), Leyland cypress (x Hesperotropsis leylandii), Chinese (Ilex cornuta) and Japanese hollies (Ilex crenata), Asian azaleas (Rhododendron spp.), daylilies (Hemerocallis spp.), and large areas of turfgrass. These landscapes lack the diversity necessary to support biodiversity and a wide range of ecosystem services (Figure 12–14).

An easy way to increase the diversity of any yard is to limit lawn areas to sites where turfgrass is the most functional choice, such as outdoor recreation areas and areas that need to be kept low to preserve visibility and for access routes to other parts of the property. Excess turf areas can be converted into woodland or meadow-style plantings (Figure 12–15), or used to grow edible plants. Within turf areas, tolerating some flowering broadleaf weeds can increase diversity and provide important resources for pollinators (Figure 12–16).

Create a variety of habitats and maximize diversity by including plants that mature at different heights, produce flowers and fruit throughout the growing season, and include both deciduous and evergreen species. Provide multiple areas in the landscape where birds and pollinators can gather nectar, pollen, and seeds from flowers. Within these areas, include groups of at least three to five plants of each species. This allows bees, butterflies, and other species to forage more efficiently by minimizing the distance they must move from plant to plant.

To create a continuous food supply, aim to have at least three different species native to the region in bloom during each growing season, from early spring through late fall. Provide nesting habitats for a variety of species by including both shade and understory trees. Adding birdhouses, birdbaths, snags, and brush piles further supports wildlife. Include habitat signs (Figure 12–17) to communicate to friends and neighbors that this landscape supports local wildlife, and inspire others to install similar plantings.

Plant in layers

Creating vertical layers in the landscape is important for sustaining diversity and maximizing ecological function. Vertical layers include different plant heights, from tall canopy trees to low-growing ground covers. As part of the Eastern Temperate Forest, natural plant communities within North Carolina may include five distinct layers: canopy, understory, shrub, herbaceous, and ground layer. Designing landscapes so that each layer is represented with native plants provides the most benefit to the local ecosystem and supports the widest array of species.

Canopy Layer

The tallest trees in a forest or landscape create the canopy. Canopy species typically mature at 40-feet to 80-feet tall, or more. The nuts and seeds of canopy trees such as oak (Quercus spp.) and hickory (Carya spp.) are important food sources for many mammals. Tree foliage supports a wide range of caterpillars that birds eat. Although few canopy trees have spectacular flowers, the blossoms of trees such as red maple (A. rubrum) and tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) provide important nectar sources for bees.

In a landscape setting, we often describe canopy trees as shade trees, in reference to the important cooling service they provide. From a design standpoint, canopy trees give a landscape structure and are major design elements in any yard. Most canopy trees are deciduous, and their annual cycle of growing and shedding leaves is a dynamic landscape element, reflecting the changing seasons. Fallen leaves left in place on the ground return nutrients to the soil and serve as a natural mulch layer that provides habitat to firefly larvae, click beetles, and other ground-dwelling species Table 12–1 lists some commercially available native canopy trees suitable for NC landscapes.

Table 12–1. Examples of native canopy trees for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Red maple | Acer rubrum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain1 |

| River birch | Betula nigra | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Persimmon | Diospyros virginiana | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| American beech | Fagus grandifolia | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Black gum | Nyssa sylvatica | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Loblolly pine | Pinus taeda | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| White oak | Quercus alba | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Pin oak | Quercus palustris | Piedmont |

| Willow oak | Quercus phellos | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| Shumard oak | Quercus shumardii | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Live oak | Quercus virginiana | Coastal plain |

1The NC sandhills are part of the NC coastal plain.

Understory Layer

In most forests, trees that mature from 20-feet to 40-feet tall make up the understory. Many understory trees produce showy blossoms in spring and are important early nectar sources for pollinators. Because they evolved to grow beneath taller trees, understory trees typically tolerate shade. When grown in sunnier sites, their flower production is more prolific and growth habit denser and more compact. Like their taller canopy counterparts, understory trees provide many resources for insects, birds, and other wildlife. In the landscape, plant understory trees in combination with canopy trees, or on their own where a smaller stature tree is desired. See Table 12–2 for suggestions of native understory trees.

Table 12–2. Examples of native understory trees for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Red buckeye | Aesculus pavia | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| Downy serviceberry | Amelanchier arborea | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Ironwood | Carpinus caroliniana | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Redbud | Cercis canadensis | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Flowering dogwood | Cornus florida | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Carolina silverbell | Halesia carolina | Mountains, piedmont |

| American holly | Ilex opaca | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Sourwood | Oxydendrum arboreum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

Shrub Layer

Many shrubs produce flowers, seeds, or fruits that support birds and insects and provide color and interest in the landscape. Shrubs are an important component of NC forests where moisture is abundant, but may be sparser or noticeably absent in drier habitats. Table 12–3 lists a few of the many native shrubs suitable for NC landscapes.

Table 12–3. Examples of native shrubs for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| American beautyberry | Callicarpa americana | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| Buttonbush | Cephalanthus occidentalis | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Sweet pepperbush | Clethra alnifolia | Piedmont (eastern), coastal plain |

| Dwarf fothergilla | Fothergilla gardenii | Coastal plain |

| Inkberry | Ilex glabra | Piedmont (eastern), coastal plain |

| Winterberry | Ilex verticillata | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Yaupon holly | Ilex vomitoria | Coastal plain |

| Virginia sweetspire | Itea virginica | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Wax myrtle | Morella cerifera | Piedmont (eastern), coastal plain |

| Catawba rhododendron | Rhododendron catawbiense | Mountains, piedmont |

| Arrowwood | Viburnum dentatum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Possumhaw | Viburnum nudum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

Herbaceous Layer

The herbaceous layer, which is composed of plants lacking woody stems, includes wildflowers, grasses, sedges, and ferns and is the most diverse layer in most natural communities and landscapes. Although some herbaceous natives have annual or biennial life cycles, most are perennials. Those with showy flowers are favorites with gardeners and landscape designers.

There are hundreds of native perennials suitable for landscapes. You can find herbaceous plants for sun or shade, wet or dry conditions, with mature heights ranging from a few inches to several feet. To support local pollinators, select at least three different plant species to bloom in each growing season: spring, summer, and fall. Tables 12–4, 12–5, and 12–6 provide examples of spring-, summer-, and fall-blooming native perennials for NC landscapes. See Table 12–7 for examples of native grasses and sedges, and Table 12–8 for native ferns.

Table 12–4. Examples of native spring-blooming perennials for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern bluestar | Amsonia tabernaemontana | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Eastern columbine | Aquilegia canadensis | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| White false indigo | Baptisia alba | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| Green and gold | Chrysogonum virginianum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Lanceleaf coreopsis | Coreopsis lanceolata | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Trailing phlox | Phlox nivalis | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Sundrops | Oenothera fruticosa | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Pink beardtongue | Penstemon australis | Piedmont, coastal plain |

Table 12–5. Examples of native summer-blooming perennials for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Swamp milkweed | Asclepias incarnata | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Butterfly weed | Asclepias tuberosa | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Threadleaf coreopsis | Coreopsis verticillata | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| Swamp rosemallow | Hibiscus moscheutos | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Wild bergamot | Monarda fistulosa | Mountains, piedmont |

| Summer phlox | Phlox paniculata | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Mountain mint | Pycnanthemum tenuifolium | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Green-headed coneflower | Rudbeckia laciniata | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

Table 12–6. Examples of native fall-blooming perennials for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Joe-pye weed | Eutrochium fistulosum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Narrow leaf sunflower | Helianthus angustifolius | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Grass-leaf blazing Star | Liatris pilosa | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Cardinal flower | Lobelia cardinalis | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Narrow-leaf silkgrass | Pityopsis graminifolia | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Wrinkle-leaf goldenrod | Solidago rugosa | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Calico aster | Aster lateriflorus | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| New York ironweed | Vernonia noveboracensis | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

Table 12–7. Examples of native grasses and sedges for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Southern waxy sedge | Carex glaucescens | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| Gray’s sedge | Carex grayi | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| River oats | Chasmanthium latifolium | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Pink muhly grass | Muhlenbergia capillaris | Piedmont, coastal plain |

| Switchgrass | Panicum virgatum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Little bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

Table 12–8. Examples of native ferns for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Northern maidenhair | Adiantum pedatum | Mountains, piedmont |

| Southern lady fern | Athyrium asplenioides | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Marginal wood fern | Dryopteris marginalis | Mountains, piedmont |

| Cinnamon fern | Osmundastrum cinnamomeum | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Christmas fern | Polystichum acrostichoides | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| New York fern | Thelypteris noveboracensis | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

Ground Layer

The ground layer is the lowest layer in any planting, composed of plants and materials extending just a few inches above the soil surface. In nature, the ground layer is most often made up of fallen leaves in various states of decay that provide critical habitat to ground-foraging birds, along with the insects the birds hunt. In most landscapes, mulch or turfgrass dominates the ground layer. Where possible, allowing leaves to remain on the ground where they fall helps restore the natural ground layer and provides natural mulch.

None of the commonly cultivated turfgrass varieties are native to North Carolina, but there are native alternatives for areas that do not receive frequent traffic. Moss is one alternative for areas where gardeners desire a very low-growing ground cover. Moss thrives in shady areas unsuited to lawn growth, as well as in moist, acidic soils, providing a low-maintenance, attractive alternative to turf.

Low-growing, spreading perennials are effective ground covers. Adding a path of mulch or stepping stones through ground cover areas will allow people to pass through without damaging these plantings.

Table 12–9. Examples of native ground covers for North Carolina landscapes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | NC Regions Native |

|---|---|---|

| Pussytoes | Antennaria plantaginifolia | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Pennsylvania sedge | Carex pensylvanica | Mountains, piedmont |

| Green and gold | Chrysogonum repens | Mountains, piedmont |

| Partridgeberry | Mitchella repens | Mountains, piedmont, coastal plain |

| Allegheny spurge | Pachysandra procumbens | Mountains |

| Creeping phlox | Phlox stolonifera | Mountains, piedmont |

| Heartleaf foamflower | Tiarella cordifolia | Mountains, piedmont |

| Creeping blueberry | Vaccinium crassifolium | Piedmont, coastal plain |

Figure 12–11. A parking lot planting has reflected heat, reduced water infiltration, and limited soil volume, and is surrounded by impervious surfaces unlike conditions found in most natural areas.

LEEROY Agency, Pixabay CC0

Figure 12–16. The common meadow violet (Viola sororia), a larval host of fritillaries, makes an attractive and functional addition to turfgrass in the landscape.

James Steakley, Wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0

Summary

Native plants contribute to the health of the local ecosystem through complex relationships with native insects and wildlife that have evolved over thousands of years. Native plants help create healthy, sustainable, low-maintenance landscapes that are likely to thrive over the long term. Select the right native plants, plant them in the right place, and care for them until the plants are successfully established. That is how gardeners create resilient landscapes capable of surviving the stresses of our variable climate.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a native plant?

There are many definitions, but native plants are those that have evolved naturally in a region without human intervention. Because they have evolved over thousands of years with the elements, animals, insects, and other plants, native plants make up an integral part of the survival of our ecosystem.

2. Are native plants better than “regular” plants I can buy at a nursery?

From a landscape design perspective, native plants are not necessarily better than traditional nursery stock. Some nonnative plants may have more colorful blooms or foliage than their native counterparts. A native wildflower garden may appear understated compared to a bed planted with petunias, lantana, or caladiums. However, native plants are well-adapted to the environment and have co-evolved with organisms in the local ecosystem. They provide more ecosystem services, such as food and shelter for pollinators and wildlife, than nonnative plants. If you appreciate the elegance and value of native plants, you strengthen your local ecosystem network.

3. If I plant natives, will I have to water and fertilize them?

Native plants in a residential landscape are in far different conditions than in their natural habitat. Compacted soils from construction, removal of top soil, reflected heat from buildings, runoff from paved surfaces, shade or lack of it, can all affect how a native plant performs in a landscape. Native plants are not maintenance-free, especially new plantings. A soil test will help you identify any problem areas where topsoils were removed. Leaving fallen leaves as natural mulch will help supply slow-release nutrients to your native plants. New plants require water to establish and, depending on the location, may need supplemental irrigation through hot dry periods.

4. Can I just dig up plants or collect seeds I find in the wild?

Harvesting plants from the wild can diminish natural populations, reducing diversity and putting pressure on other organisms that rely on the plants. Removing a plant from a natural environment leaves a void that is often filled with a weedy plant or invasive. Plants harvested from the wild often die after transplanting, or they perform poorly. The easiest way to have a successful native garden is to identify and preserve native plants that appear in your landscape, or purchase native plants propagated from local cuttings or seed. In addition, the NC Plant Protection and Conservation Act, administered through the Plant Conservation Program in the NC Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services, identifies legally protected plants that may not be harvested in the wild. Instead of trying to transplant a wild plant, purchase one and support nurseries propagating native plants from cuttings or seed. The USDA Forest Service does offer limited collection permits for wildflowers. Costs and stipulations vary by region and time of year.

5. My neighbor’s yard looks like a weed patch. He says the plants are native plants. Will they always look this way?

Native plant landscapes can range from formal, highly structured plantings to more natural, low-care designs. Converting a yard from turfgrass to a naturalized native garden can take several years, and some stages may appear weedier than others. Your neighbor needs to ensure the planting consists of native plants rather than invasives. Along with providing many ecological benefits, established native gardens are a rich source of colors and textures and can be quite beautiful. Incorporating design elements such as pathways, benches, fencing, or other decorative features into naturalized landscapes can provide structure and communicate that the yard is being maintained.

6. Are there any grasses native to North Carolina that can be cultivated for lawns?

While many native grasses make beautiful additions to NC landscapes, only carpetgrass (Axonopus fissufolius) tolerates frequent mowing and can be grown as a lawn grass. Carpetgrass is native to several counties in the coastal plain, where it grows in moist, open, wooded areas. Carpetgrass is less wear, drought, and cold tolerant than popular nonnative warm season turfgrasses, such as zoysia and bermuda. Described as coarse textured and greenish yellow in color, carpetgrass is mainly used for low maintenance areas that do not receive heavy traffic.

7. What percent of plants in a landscape should be native to the local ecoregion?

The ratio of native to nonnative plants necessary to sustain ecosystem services in residential landscapes has not been determined. Increasing the number and diversity of native plants in your landscape will increase its value to wildlife, but landscapes do not have to be 100% native to be ecologically functional. To design an aesthetically pleasing, sustainable, landscape that benefits the local environment, select a diversity of plants suited to the site’s growing conditions. Incorporate plants native to the region, along with noninvasive plants from other regions, where needed to fulfill the landscape design purpose.

8. Why are some native plants not available from nurseries?

Traditional nurseries may not carry native plants that are difficult to propagate, are slow-growing, or are not well-adapted to nursery production systems. Some nurseries, however, specialize in native plants and carry native azaleas (Rhododendron spp.) and spring ephemerals such as trillium (Trillium spp.). While it is possible to include slow growers in landscapes, they are expensive and may be hard to find. Other native plants are not offered due to low demand or because they do not perform well in landscape settings.

9. Are native plants pest free?

Native plants can have serious pest and disease issues, especially from introduced pests to which they have no resistance. Examples include the emerald ash borer, a fatal pest of ash trees (Fraxinus sp.), and Dutch elm disease, a fungal disease that has decimated American elm (Ulmus americana) populations. Other introduced pests, such as Japanese beetles, can cause cosmetic damage to native plants, but rarely threaten the long-term health of established plantings.

Native insects can also become pests in unnatural conditions where the insects are not kept in check by predators and parasites. Gloomy scale on red maple (A. rubrum) is one example. In forests, gloomy scale occurs on red maples, but the pest’s populations remain low. In parking lots where the red maple is often planted, there are few natural scale predators or parasites. Reflected heat boosts the pests’ reproduction rate on already stressed trees, leading to their decline and death. Gloomy scale is such a serious problem on red maple trees in urban areas that these trees are not recommended for sites surrounded by impervious surfaces (Figure 12–19).

10. Are native plants deer resistant?

Native plants are not necessarily deer resistant. As with all plants, deer prefer to browse some native plants while they leave others alone. In areas where deer populations are high, some native plants that are frequently browsed include phlox (Phlox spp.), strawberry bush (Euonymus americanus), and Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica). Unless they are very hungry, deer tend to avoid green and gold (Chrysogonum virginianum), blue star (Amsonia tabernaemontana), inkberry (Ilex glabra), and buckeyes (Aesculus spp.). Deer damage is more likely to occur in urban and suburban areas where natural habitat is limited and there are few predators to balance deer populations.

Further Reading

Armitage, Allan M. Armitage's Native Plants for North American Gardens. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2006. Print.

Beaubaire, Nancy, ed. Native Perennials: North American Beauties. Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 2001. Print.

Bir, Richard E. Growing and Propagating Showy Native Woody Plants. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University Of North Carolina Press, 1992. Print.

Burrell, C. Colston, ed. Native Alternatives to Invasive Plants. Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 2006. Print.

Burrell, C. Colston, ed. Wildflower Gardens: 60 Spectacular Plants and How to Grow Them in Your Garden. Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 2007. Print.

Cullina, William. Native Ferns, Moss, and Grasses: From Emerald Carpet to Amber Wave, Serene and Sensuous Plants for the Garden. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2008. Print.

Darke, Rick. The American Woodland Garden: Capturing the Spirit of the Deciduous Forest. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2002. Print.

Darke, Rick, and Doug Tallamy. The Living Landscape. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2014. Print.

Druse, Ken. The Natural Habitat Garden. 1994. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2004. Print.

Dunne, Niall, ed. Great Natives for Tough Places. Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 2009. Print.

Hightshoe, Gary L. Native Trees, Shrubs, and Vines for Urban and Rural America: A Planting Design Manual for Environmental Designers. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1988. Print.

Jones Jr., Samuel B., and Leonard E. Foote. Gardening with Native Wild Flowers. 1990. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2010. Print.

Mellichamp, Larry. Native Plants of the Southeast: A Comprehensive Guide to the Best 460 Species for the Garden. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2014. Print.

Nelson, Gil. Best Native Plants for Southern Gardens: A Handbook for Gardeners, Homeowners, and Professionals. Gainesville, Florida: University Press Of Florida, 2010. Print.

Phillips, Harry R. Growing and Propagating Wild Flowers. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1985. Print.

Stein, Sara. Noah's Garden: Restoring the Ecology of Our Own Backyards. 1993. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995. Print.

Sternberg, Guy, and Jim Wilson. Native Trees for North American Landscapes. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2004. Print.

Summers, Carolyn. Designing Gardens with Flora of the American East. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2010. Print.

Tallamy, Douglas W. Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants, Updated and Expanded. 2007. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2009. Print.

Wasowski, Sally. Gardening with Native Plants of the South. 1994. Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2010. Print.

Wells, B. W. The Natural Gardens of North Carolina, Revised Edition. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002. Print.

Wilson, Jim. Landscaping with Wildflowers: An Environmental Approach to Gardening. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1992. Print.

Native Plant Identification

Adkins, Leonard M. Wildflowers of Blue Ridge and Great Smoky Mountains. Birmingham, Alabama: Menasha Ridge Press, 2005. Print.

Alderman, J. Anthony. Wildflowers of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997. Print.

Carman, Jack B. Wildflowers of Tennessee. Tullahoma, Tennessee: Highland Rim Press, 2001. Print.

Justice, William S., C. Ritchie Bell, and Anne H. Lindsey. Wild Flowers of North Carolina. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2005. Print.

Kirkman, Katherine, Claud L. Brown, and Donald J. Leopold. Native Trees of the Southeast: An Identification Guide. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc., 2007. Print.

Nelson, Gill. Atlantic Coastal Plain Wildflowers. Guilford, Connecticut: Falcon Guide, 2006. Print.

Porcher, Richard Dwight, and Douglas Alan Rayner. A Guide to the Wildflowers of South Carolina. Columbia, South Carolina: The University of South Carolina Press, 2001. Print.

Schafale, Michael. Guide to the Natural Communities of North Carolina, Fourth Approximation. 2012. North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

Sorrie, Bruce A. A Field Guide to the Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Print.

Spira, Timothy P. Wildflowers and Plant Communities of the Southern Appalachian Mountains and Piedmont: A Naturalist's Guide to the Carolinas, Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Print.

Weakley, Alan S. Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2012. PDF file.

Chapter Text Hyperlinks

North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox

Ecoregions of North America, US Environmental Protection Agency

Guide to the Natural Communities of North Carolina, Fourth Approximation, by Michael P. Schafale (March 2012)

Prevalent Natural Communities in North Carolina, by North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

National Invasive Species Information Center (NISIC)

North Carolina Invasive Plant Council

Southeast Exotic Pest Plant Council

A field guide for the identification of invasive plants in southern forests, by U.S. Forest Service Southern Research Station

Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health

North Carolina Native Plant Society

North Carolina Botanical Garden, UNC at Chapel Hill

Ecosystem Services Fact Sheet, Ecological Society of America

Butterflies in Your Backyard, AG-636-02

Managing Backyards and Other Urban Habitats for Birds, AG-636-01

For More Information

NC State Resources

- Butterflies in Your Backyard, AG-636-02

- Going Native: Urban Landscaping for Wildlife with Native Plants (10:18 minutes)

- Landscaping with Native Plants: Environmental Policy Driven Markets (37:00 minutes)

- Managing Backyards and Other Urban Habitats for Birds, AG-636-01

- Pollinator Conservation Guide, Growing Small Farms, NC State Extension, Chatham County

- Reptiles and Amphibians in Your Backyard, (AG-744)

- Southeastern Flora, Southeastern US Plant Identification Resource

- Wildlife-Chapter 20, NC Extension Gardener Handbook

More NC State Resources

Other Resources

- Bringing Nature Home by Dr. Doug Tallamy, University of Delaware

- Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health

- Ecoregions of North America, US Environmental Protection Agency

- Ecosystem Services Fact Sheet, Ecological Society of America

- A field guide for the identification of invasive plants in southern forests, by U.S. Forest Service Southern Research Station

- Guide to the Natural Communities of North Carolina, Fourth Approximation, by Michael P. Schafale (March 2012)

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, The University of Texas at Austin

- The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, by Rick Darke & Doug Tallamy (3 min)

- National Invasive Species Information Center (NISIC)

- The Natural Gardens of North Carolina, 2nd Edition, by B. W. Wells

- NC Botanical Garden, UNC at Chapel Hill

- NC Invasive Plant Council

- NC Native Plant Profiles

- NC Native Plant Society

- NC Natural Heritage Program

- Prevalent Natural Communities in North Carolina, by North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

- Southeast Exotic Pest Plant Council

- USDA Plants Database

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wildflowers in Bloom Wildlife Friendly Landscapes

Videos

- Bird-Friendly Native Plants of the Year – Audubon North Carolina (3:45 minutes)

- North Carolina Botanical Garden – Chapel Hill, NC Video 1 (2:30 minutes) Video 2 (9:48 minutes)

- Native Plants of the Sarah P. Duke Gardens (2:05 minutes)

Contributors

Author: Charlotte Glen, Extension Agent Agriculture—Horticulture, Chatham County

Contributions by Extension Agents: David Goforth

Contributions by Extension Master Gardener Volunteers: Margaret Genkins, Deborah Green, Lee Kapleau, Karen Damari, Chris Alberti, Harriet Walls, Susan Sunflower

Content Editors: Lucy Bradley, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist, Urban Horticulture, NC State University; Director, NC State Extension Master Gardener program; Kathleen Moore, Urban Horticulturist

Copy Editor: Barbara Scott

How to cite this chapter:

Glen, C.D. 2022. Native Plants, Chapter 12. In: K.A. Moore, and. L.K. Bradley (eds). North Carolina Extension Gardener Handbook, 2nd ed. NC State Extension, Raleigh, NC. <http://content.ces.ncsu.edu/12-native-plants>

Publication date: Feb. 1, 2022

AG-831

Other Publications in North Carolina Extension Gardener Handbook

- 1. Soils & Plant Nutrients

- 2. Composting

- 3. Botany

- 4. Insects

- 5. Diseases and Disorders

- 6. Weeds

- 7. Diagnostics

- 8. Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

- 9. Lawns

- 10. Herbaceous Ornamentals

- 11. Woody Ornamentals

- 12. Native Plants

- 13. Propagation

- 14. Small Fruits

- 15. Tree Fruit and Nuts

- 16. Vegetable Gardening

- 17. Organic Gardening

- 18. Plants Grown in Containers

- 19. Landscape Design

- 20. Wildlife

- 21. Youth, Community, and Therapeutic Gardening

- Appendix A. Garden Journaling

- Appendix B. Pesticides and Pesticide Safety

- Appendix C. Diagnostic Tables

- Appendix D. Garden Tools

- Appendix E. Season Extenders and Greenhouses

- Appendix F. History of Landscape Design

- Appendix G. Permaculture Design

- Appendix H. Community Gardening Resources

- Appendix I. More NC State Resources

- Glossary

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.