Outline

Understanding Space in Landscape Design

Six Steps to a Landscape Design

Step 3: Identify Activities and Uses for the Landscape

Step 4: Locate and Develop Use Areas

Case Study—Think about IPM: Failing Tree

Appendix A Garden Journaling

Appendix F History of Landscape Design

Appendix G Permaculture

Objectives

This chapter teaches people to:

- Explain the basic principles of landscape design.

- Describe the process of creating a landscape design.

- Recognize the environmental factors that influence landscape design.

- Identify design opportunities for water, energy, and wildlife conservation.

- Recommend appropriate plants for a landscape given site and design conditions.

- Understand the history of landscape design.

Introduction

Landscape design is both an art and a purposeful process. It is the conscious arrangement of outdoor space to maximize human enjoyment while minimizing the costs and negative environmental impacts. A well-designed home landscape is aesthetically pleasing and functional, creating comfortable outdoor spaces as well as reducing the energy costs of heating and cooling the home. It offers pleasure to the family, enhances the neighborhood, and adds to the property’s value. With a little forethought and planning, the designer can maximize the property’s use and people’s enjoyment of it; establish a visual relationship between the house, its site, and the neighborhood; and contribute to a healthy local ecosystem.

The planning process, possibly the most important aspect of residential landscaping, is often neglected. We can see the effects: overcrowded and overgrown plantings, lawns with scattered shade trees, a narrow concrete walk, trees and shrubs planted too close to structures (Figure 19–1), every plant a different species, or too many of the same plant. The result can be unattractive and may not serve the family's needs. Good landscape design creates a satisfying environment for the user while saving time, effort, and money and benefiting the environment.

In this chapter, we review the principals of design, including understanding the use of space in the landscape. These principles can be applied by using six steps to create an attractive, functional landscape. The steps provide an organized approach to developing a landscape plan, including an in-depth look at specific design considerations to improve the landscape environment. Appendix F gives a brief history of landscape design. To learn more about landscape design, refer to the additional resources at the end of this chapter.

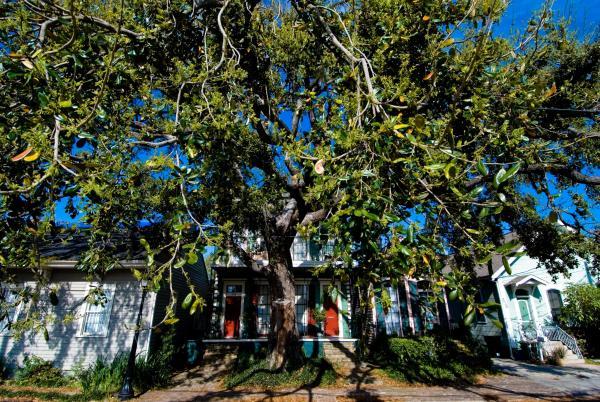

Figure 19–1. Mature size should always be taken into consideration when selecting plants. This tree is far too large for this tiny front yard, and is completely overpowering the landscape and the house.

Scott S (scott*eric), Flickr CC BY 2.0

Design Principles

When we develop and implement a landscape design, we rely on a dynamic process that addresses all aspects of the land, the environment, the growing plants, and the user’s needs. This process ensures a pleasing, functional, and ecologically healthy design. Fundamental design concepts—scale, balance, unity, perspective, rhythm, and accent—form the basic considerations in design development. Simplicity, repetition, line, variety, and harmony are organizing principles. We use these principles to apply design concepts to landscape features, such as plants and hardscape materials. Understanding spatial organization is also integral to the art of landscape design. The resulting design is implemented in three-dimensional space. The space changes as we use it, as plants grow, and as nature contributes its full range of environmental conditions.

Design Concepts

These basic concepts underlie a design’s composition: scale, balance, unity, perspective, rhythm, and accent.

Scale is the proportion between two sets of dimensions—for example, the height and width of a tree compared to a house, or the size of a plant container compared to an entryway. Carefully consider both the mature height and spread before including a plant in the landscape (Figure 19–2). If the full-grown size is too large, a plant can overwhelm the design. If plants remain small at maturity, they may look inappropriate as a background border.

Balance refers to creating equal visual weight on either side of a focal point, creating a pleasing integration of elements. There are two types of balance: symmetrical and asymmetrical. Symmetrical balance describes a formal balance with everything on one axis, duplicated or mirrored on both sides. Symmetry is commonly seen in formal gardens (Figure 19–3). Asymmetrical balance describes an equilibrium achieved by using different objects. For example, if a large box is placed on one side of a scale, it can be counterbalanced by several smaller boxes placed on the other side. Asymmetrical balance occurs in landscaping when a large existing tree or shrub needs to be balanced out by a grouping or cluster of smaller plants (Figure 19–4). Balance can also be achieved by using color or texture.

Unity is achieved when different parts of the design are grouped or arranged to appear as a single unit. The repetitions of geometric shapes, along with strong, observable lines (Figure 19–5), contribute to unity. Ground covers and turfgrass act as unifying elements in a landscape. A unified landscape provides a pleasant view from every angle. A landscape with too many ideas in a small space lacks unity. Too many plant varieties, accent plants, lawn accessories with contrasting forms, textures, or colors violate the principle of unity by distracting the viewer from a coherent visual theme that unites the landscape’s individual elements.

Perspective is our visual perception of three-dimensional space. Certain techniques can make a space appear small, while others can make a space seem larger. Usually the goal in residential landscaping is to make a space appear larger. A strong accent in the center of a space can draw one’s eye and make the space seem larger (Figure 19–6). Overhead tree canopies or structures make the space feel more confined or smaller. Many backyards have an area of grass surrounded by a border of shrubs. The border brings the eye to a boundary and makes the space appear confined.

Effective use of color can expand the space. Distant objects appear fine-textured and gray to the eye, so using gray, fine-textured plants at the landscape boundary can expand the apparent distance between the viewer and the plant. Tapering walkways or plantings toward a vanishing point can also create an illusion of distance. Using strong colors and coarse textures in the front of a border help to expand the area. To make the space appear smaller, reverse this concept and use strong colors and coarse textures in the rear and softer colors and finer textures in the front.

Rhythm is the repetition of design elements. Repetition helps draw one’s eye through the design. Rhythm results when elements appear in a definite direction and in regular measures. Both color and form can be used to express rhythm (Figure 19–7).

Accent is the inclusion of an element that stands out in an orderly design. For example, silvery leaves stand out against a background of fall red maple leaves (Figure 19–8). Without accent, a design may be static or dull. An accent can be a garden accessory, plant specimen, a plant composition, or a water feature. Boulders are often used as accents, but they can be overused. To look natural, boulders should be partially buried. Water does not spring from the highest point of land in nature. So to appear most natural, water features should have their source below grade of other landscape features.

Figure 19–2. Scale is an important element to consider. The cannas are tall enough to be a background plant in this bed. If the lantanas (seen in the foreground) were moved to the back they would be visually lost in the design.

Lucy Bradley CC BY 2.0

Figure 19–3. Symmetry is seen here with the mirror image fence posts, hedges, and shrubs. Symmetry in a garden is a more formal style.

Leimenide, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 19–4. Asymmetrical elements of the tree and bench on the left balance out with lower growing begonias and a sundial on the right to form a pleasing design.

Susan Strine CC BY 4.0

Figure 19–5. Unity is demonstrated using lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) to line a path.

Old_Man_Leica, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0

Figure 19–6. The decorative gate draws the eye to the back of this small side landscape making it appear larger.

J Brew (brewbooks), Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 19-7. Rhythm is seen in this landscape by repeatedly using the dome-shaped boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) and the weeping cherry (Prunus cerasus).

Marcia Boyle CC BY 4.0

Figure 19–8. The silvery leaves of this blue star juniper are accented against the fall color of Japanese maple leaves.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Understanding Space in Landscape Design

We customarily use paper or a computer to create a landscape plan. When we implement the plan, we build a three-dimensional space in which people engage. People engage in the world and are affected by it every time they venture outdoors. Landscapes are dynamic spaces—they are always changing. Plants change with the seasons, grow, age, flower, reproduce, and provide habitat for other creatures and species. In a well-calculated landscape plan, the designer addresses elements of space and change. Beyond this, our experience in a landscape becomes a major factor in the overall impact a place has on our lives. In landscape planning, better outcomes and richer environments can be achieved when we understand spatial definition and the importance of transition between different land uses and different planes of space.

The world consists of three different planes of space that affect human experience. As we engage in the world, we are always surrounded by these three planes—horizontal, vertical, and overhead. As the volumes of these different planes change, the way we experience the space changes. In the landscape, for example, an enclosed space created by a dense canopy has a different feeling than an open pasture. One space is shaded and dark, while the other is sunny and open. Our purpose in understanding these differences is not to pass judgment on them. Rather, it is to accept that these different kinds of spatial experiences exist. We recognize that the more transitional spaces a person goes through in moving from a completely enclosed environment to a completely open environment, the more seamless and connected the experience becomes.

Addressing the hierarchy, or order, of space and scale is also important. Specifically, land use can be determined by the scale of a space. Roads, for example, have a defined hierarchy. All lanes may be a standard size (large enough to accommodate one vehicle), but streets are designed to accommodate a certain amount of traffic. As such, a level one road such as an interstate may have four lanes in each direction. A level two road has only three lanes in each direction. A level three road has two lanes in each direction, and a level four road may have only a single road in one direction. By developing a hierarchy of land uses within a landscape, different landscape elements can be appropriately scaled to accommodate different activities and to create different experiences. For example, a level one path to the front of the house should be scaled to accommodate at least two individuals (41⁄2- to 5-feet wide). As paths connect, they should gradually scale down in size. So all the paths that connect to the main entrance path should be level two (21⁄2- to 3-feet wide). And paths in the landscape meant for an individual experience should be level three (1- to 21⁄2-feet wide). Likewise, space designed for an individual is smaller than space for a small group or a large party.

Spatial definition of the three planes of space also helps to enhance our experience. The more clearly defined the plane, the easier it is to interpret. For example, a walkway that is defined using a hardscape such as brick clearly sends a message to people that this surface is for walking. What prevents someone from walking on this path? If the horizontal ground plane is clearly defined, then people intuitively understand where they should walk and where they should not. What prevents someone from cutting through a landscape? A designer can change the horizontal ground plane to reduce unintended land use by planting a tall ground cover. The increased vertical plane makes cutting through the landscape and not using the designated path undesirable.

Understanding three-dimensional space in landscape design is essential. Each plane of space and the transitions between planes are discussed in more detail below. We also discuss how to organize landscape spaces during the design process by using garden rooms, focal points, patterns, and geometry to create functional, appealing spaces.

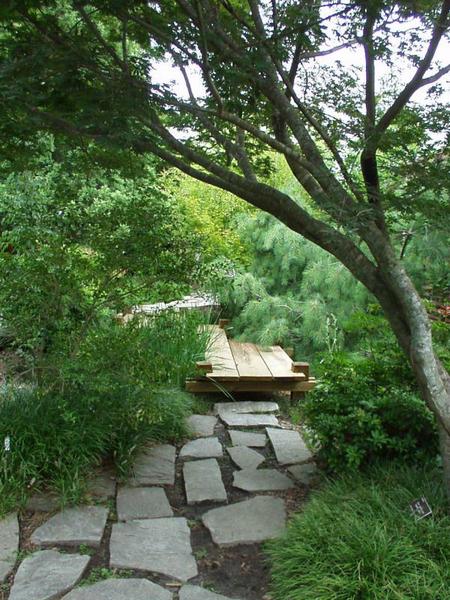

Horizontal Ground Plane

The ground plane functions as the floor of the landscape. Examples include lawns, patios, terraces, decks, and walkways. This plane influences the route by which people move through and experience the landscape. Materials can vary significantly, including compacted soil; plant materials such as lawn or moss and ground covers; crushed gravel; man-made products such as concrete, bricks, and rubber; and wood surfaces and products like lumber, mulch, and bark chips. Figure 19–9 illustrates the use of different materials to define the horizontal ground plane for walking through the landscape. The lower path is defined using irregular flagstone set in screenings, while the upper path is constructed of wood. Note the elevation change of a single step. People risk tripping and falling when an elevation change is one step or less. To intuitively heighten our attention, the designer has changed the materials of the ground plane. In addition, the ground covers on either side of the path begin to build up the vertical plane. The path, therefore, is clearly defined. Imagine someone moving through the landscape and reaching the point before he or she steps up to a new height. Notice how the tree helps to create a gateway by increasing the vertical plane and adding an overhead plane. Our senses are heightened to pay attention to change. Notice how the elevated walkway is further defined with small posts that mark the walkway’s edges by a subtle increase in the vertical plane. As we pass through this gateway, notice how the vegetation that flanks the path also increases in height. This further defines the pedestrian corridor. We know where to walk.

Vertical Plane

Vertical planes create the outdoor walls, enclose the space, and serve as a backdrop to enhance other elements within the space. Vertical elements frame certain views both inside and outside of the space and terminate the sightline. Examples in the landscape include trees, shrubs, walls, fencing, lampposts, and pillars. The vertical plane is defined by building facades that create an outdoor hallway. The transition from the ground plane (defined by a lawn or walkway) to the vertical plane is created through the use of edging, ferns, and vines (Figure 19–10). Breaking down the space into its elements, the ground plane is defined by the brick walkway. Moving from the horizontal plane to the vertical plane, the vertical plane is built up with the introduction of edging on either side of the path, then with the ferns along with the vines and the brick. The walls terminate our sightline and direct our vision toward the terminus in the path and the change in land use up ahead.

Vertical planes in the landscape do not need to be continuous to define space. For example, a repeating allée of trees, which can be used to define both a pedestrian and a vehicle corridor, is not a solid wall. The viewer mentally fills in the blanks in the allée to create the feeling of entering a tunnel. When trees and plants are used in succession and repeated, movement is created (Figure 19–11). One’s eye continuously moves to the next set of trees, and the user is propelled forward.

Overhead Plane

The overhead plane defines the ceiling of an outdoor area that we often feel more than see. This plane serves as protection from the elements. Psychologically it provides a sense of shelter and protection. The feeling of “being under” creates a strong sense of enclosure. The overhead plane can provide an exceptional sensory experience from the character and color it creates as sun and shade patterns land on leaves. Our sensory experience also changes as the height of the overhead plane rises or falls with the tree canopy, with steps or paths that move up or down within the horizontal ground plane, and with the gradual transition that happens as we move from a completely open to a completely closed environment. Examples of overhead planes include tree canopies, overhead structures, awnings, and umbrellas. In Figure 19–12, the overhead plane is established by a continuous trellis with a repeating motif inspired by carrots. The trellis that creates the overhead plane includes colored plexiglass that casts a colored reflection on the walkway. The reflection changes as the sun moves across the sky. As the planted vines fill out seasonally, one’s experience of walking under the gigantic carrot trellis changes. Someone may even identify with a rabbit and wonder what it must be like to run through the garden undetected. The space goes from being open to being enclosed.

Transitional Spaces

Transitional spaces are the spaces that connect one outdoor area to the next; examples include doorways, hallways, and platforms. These spaces also provide transitions between the different planes of space. Well-defined transitional spaces use exposure to similar materials (such as plants and paving) to gradually introduce new spaces to people from one outdoor area to the next. Examples of transitional spaces or transitional elements include entrance gates, paving changes, planted alleys, gateway arbors, edging, and bridges.

Figure 19–13 illustrates the use of a gateway as a major transitional element within a garden. Transitional spaces help to set the stage for the adventure of being in the landscape and moving from one place to the next. The scale of this gateway intuitively suggests that we are leaving one type of garden space and going into another with a different character. In the foreground, the horizontal ground plane changes as the Chapel Hill gravel paving meets the granite edging. The edging is still a part of the horizontal ground plane. As the paving meets the granite curbing, it begins building up the vertical plane. The vertical plane continues to grow with the increase in height created by plants. The paving also changes under the gateway to a gray flagstone paving pattern. As we move out of the structure, the horizontal ground plane transitions into informal gray crushed granite fines. Note that the gray color helps to create a transition among all these different elements. The large structure completely encloses the user. Despite the large size, the structure is scaled to human size and the volume of space is considerably smaller than the next space you enter. As we exit the structure, the volume of space increases as the overhead plane is determined by the height of the tree canopy. This is a very common pattern used in architecture. The feeling generated by this space is used in churches across the world. Imagine entering a church. The entrance corridor usually has a low ceiling. Then the overhead plane is elevated in the main body of the church, rising to become a cathedral ceiling that evokes an emotional response in the user, frequently one of awe.

Garden Rooms

A room can be defined as a space enclosed by walls, a floor, and a ceiling, as well as a place where activities happen. This same definition applies when describing an outdoor room, with one difference. The materials used to define an outdoor space are dynamic and in some cases lack a ceiling or overhead plane. Garden rooms are the destinations within a landscape. Even small properties have enough space to accommodate a single room. The scale should be determined by the room’s function. Is the space used for entertainment? Or is the space used by a single individual—say for reading? Who is using this space—young children, teenagers, adults? The character of the space can be defined using materials that address both the function and the users. Each plane of space should be defined. The furniture in the room should address the users’ needs and express the character that distinguishes the space. Examples of garden rooms include an outdoor dining room, vegetable garden, reading room, entertainment space, kitchen, fire pit, and playground. Figure 19–14 is a large outdoor room. We enter the room through a doorway created by a bump out of the building façade on one side and a half wall made of the same material on the other side. The ground plane consists of a different stone material. The mounted wall fountain is centered on the entrance into this garden room to grab our attention and entice us into the room. The fountain also muffles the sounds of voices as people engage in conversations. As we enter the room, the ground plane increases, the walls are moved back, and the volume of the space increases. The rhododendron planted above the wall further affects the scale of the space and increases the feeling of enclosure. The furniture color is influenced by the blue hues of the plants and stone. Figure 19–15 is an outdoor dining room for two. In this residential outdoor dining area scaled for two, the ground plane is defined with flagstones set in granite fines. The ground plane is defined differently from the walkway because the material has changed and the space has increased in volume. The edges of the patio are transitioned into the vertical plane with the granite curb edging. The plants immediately surrounding the patio are low growing and increase in size moving away from the patio. Both the perennials and the trees help to define the scale of the space. Notice how the ceramic pots repeat the color of the furniture.

Focal Points

Focal points consist of carefully placed objects that direct a person’s line of sight. Their purpose in the garden is to propel movement and entice the user to make a decision: How do I proceed at this bend in the path? Do I continue down the path that offers the same experience or choose the one that teases the senses by offering a sculpture, a specimen tree, a bridge, or an interesting boulder? When a focal point is well-placed on a user’s journey, he or she does not feel manipulated. The journey through the garden is like a story that starts when one enters the garden. The story continues as one moves through twists and turns along a path, guided by focal points that foreshadow what happens next. Eventually a climax in the garden journey occurs at a destination—the garden activity room. The story, however, is not over. It resumes as one leaves the room and the gradual transition out of the space begins to move to the next destination or to leaving the garden.

In Figure 19–16, the building has an interesting roof line with a wind vane on top. The building has an interesting roof line with a wind vane on top. Although we cannot see what it is, the wind vane grabs our interest from far away. More than likely, curiosity drives us to discover what is ahead. Figure 19–17 is our focal point destination. On arriving at the wind vane, we discover the quaint colorful building, which houses the restroom for the garden. While the building is a strong focal point that functions as a driving force within the garden, smaller objects within the garden—such as garden art or plant specimens—also serve to propel us on a journey.

Pattern Language

Pattern language is a philosophy developed by Christopher Alexander (Professor Emeritus of Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley). Pattern language describes recognizable patterns in nature and human society that have developed over the ages and impact the way people live. Dr. Alexander defined the concept of a pattern language in the 1970s and spent his career studying patterns in the landscape created by nature and in society that influence lifestyles, communities, and architecture. His books, including The Timeless Way of Building and A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, have influenced the way designers (architects, landscape architects, interior designers, and planners) create the spaces we use in daily life. As a result, Professor Alexander’s ideas have affected millions of people. The number of patterns that can be observed and experienced daily is innumerable. Incorporating patterns into the garden experience enhances the user experience. In Figure 19–18, a window garden is a pattern that brings the outdoor environment closer to home. A window garden breaks up the built outdoor facade, and it changes the view of the outdoor environment from the outside and inside of the building. The human eye is trained to see what is in the foreground and tends not to notice the things faraway as much. In Figure 19–19, an edible garden is a pattern built on humanity’s agrarian roots and driven by activity. To live, people must eat. The ability to sustain ourselves by growing food is empowering. Figure 19–20 provides a bench in the garden for sitting. It seems like such a simple pattern. Yet magical life experiences take place on benches—engagements, first kisses, lunch. A bench provides an opportunity to become a part of the garden, not just an observer in the garden. A garden seat is used if there is a view, something of interest around it. It is not used if a view does not exist.

Garden Geometry

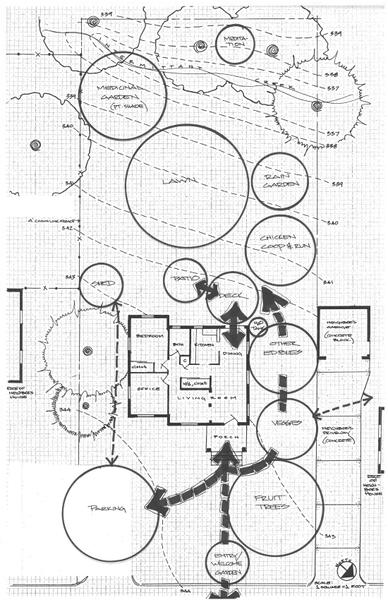

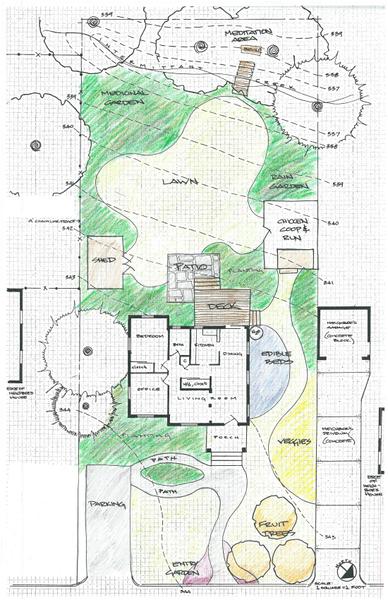

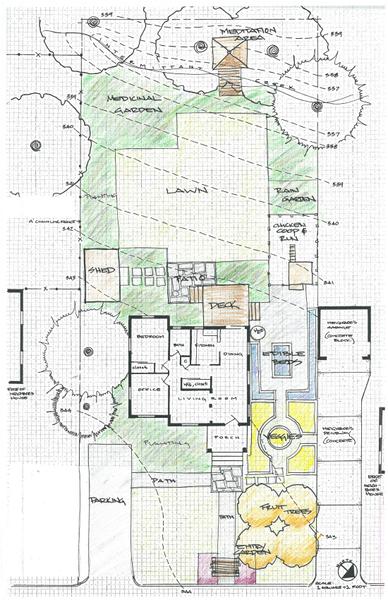

Geometry is part of the everyday world and influences the places where we live. A direct relationship exists between two objects on a plane. Because this relationship exists, a landscape designer must pay attention to the architecture before situating new objects or creating new spaces. Regardless of the geometry selected (for example, rectilinear, curvilinear, radial, or arctangent), the space and proposed objects must relate to the existing architecture (Figure 19–21a-d). The first image is a bubble diagram used for determining best locations for required activities and how much space those activities need, and for studying the relationship and circulation between activities and locations. The next step is determining which layout (geometry) is most appropriate. The following geometries are all based on the same bubble diagram. Note that everything in the bubble diagram remains the same. Only the SHAPE of each element changes.

Invisible guidelines extend out of the building at different angles of different degrees. A grid can be formed using known points on the architecture, such as the corner of the building, the center line of the window or door, and the edge of a porch. Objects placed in the landscape should have a direct geometric relationship with the building and with each other. For example, by placing a specimen tree on the centerline of a bay window, the designer ensures that the tree becomes a focal point for users looking outside into the garden from within a building.

It is important to understand that there are many ways of creating space in landscape design. No one method works for each landscape plan. A carefully laid out landscape plan with defined planes and transitions combined with good geometry and including objects that relate to garden features and buildings enriches our experience and the environment.

Applying Design Principles

Simplicity, repetition, line, variety, and harmony are used in landscape design to create a visually appealing composition.

Simplicity strives to create spaces, not fill them. “Less is more.” Not every square foot of the landscape must be filled . Most residential landscapes consist of limited space, so the number of tree and shrub species used should also be limited. It is more effective to incorporate groups of one type of plant than to install one or two each of a wide variety of plants. Create simple lines and curves that add interest rather than irregular lines that might detract from the design (Figure 19–22).

Repetition in the landscape should not be confused with monotony. Repetition contributes to unity and simplicity. It makes a strong foundation for the landscape design like the chorus repeated in a song (Figure 19–23).

Line forms real and imaginary lines in the landscape and plays an important role in the creation of small and large spaces. Draw the viewer’s eye through the landscape by grouping plants or hardscape elements (Figure 19–24). The eye is unconsciously influenced by the way groupings fit and flow on both horizontal and vertical planes.

Variety created through diverse and contrasting forms, textures, and colors is a hallmark of good landscape design. By avoiding uniformity, variety reduces monotony in a design. Adding elements with opposite qualities or contrast heightens visual interest and increases viewer satisfaction with the design (Figure 19–25).

Harmony balances the other design principles by pulling the individual components together and creating a cohesive whole, ensuring that all parts of the design relate to and complement each other (Figure 19–26).

Figure 19–22. Perennial plants like woolly thyme (Thymus pseudolanuginosus), evening primrose (Oenothera spp.), and red feather reed grass (Calamagrostis × acutiflora 'Karl Foerster') do not overwhelm this tiny backyard.

Patrick Standish, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 19–25. There is a wide variety of leaf textures, sizes, and colors as well as variety of hardscape elements that keep this small space interesting.

John Weiss, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0

Figure 19–26. Harmony is seen in this Japanese garden, all the design components relate to each other to create a cohesive whole.

John Weiss, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0

Six Steps to a Landscape Design

In the first part of this chapter, we introduced the principles and concepts that underlie landscape design. In this section, we focus on the mechanics of developing a landscape plan. Planning a residential landscape begins with evaluating the entire space and the overall desired effect of the final design. We begin the design process by determining the user’s needs and desires and the site’s environmental and physical conditions. With this information, the desired features—such as trees, shrubs, grass, walkways, parking areas, a vegetable garden, patio, deck, mailbox, screening wall, and outdoor lighting—can be organized into a cohesive design. By using the following six steps, we can take a straightforward, organized approach to developing and implementing a landscape that reflects the user’s wants and needs and allows for future growth and change.

Step 1: Develop a Base Plan and Site Inventory

Step One: Develop Base Plan and Site Inventory

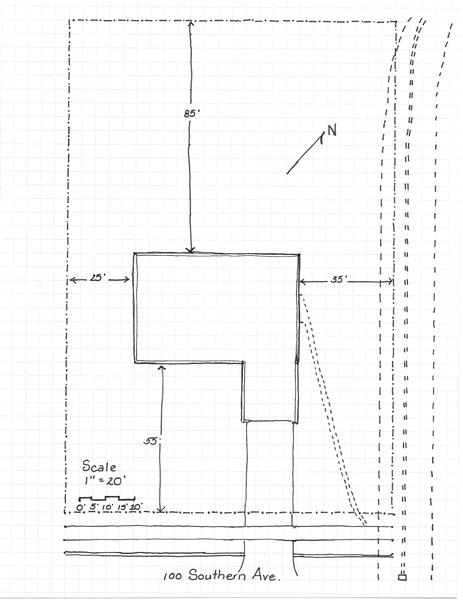

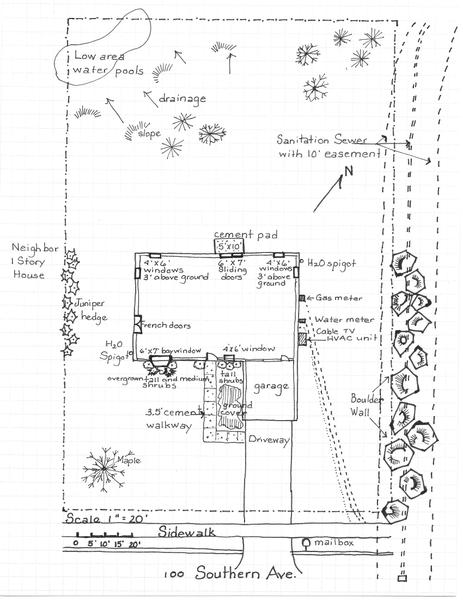

A base plan is a bird’s eye view of the site drawn to scale. A plot plan of the property, as shown in Figure 19–27, is an excellent place to start. Sometimes a plot plan is provided when property is purchased. If not, check with the local county assessor’s office or the NC County GIS, Tax and Deed website. The plot plan should include property lines, show the placement of the house on the property, and indicate the driveways, easements, and any other limitations. Be sure to check for any setbacks or streams on the property that could have their own set of legal parameters. Locating the exact property boundaries is important when a fence is part of the final design. Most property boundaries do not extend all the way to the road. Plants or hardscape installed in a state, county, or city right-of-way, such as between a sidewalk and the road, may be torn up for roadwork or to access utilities.

Next, gather and record information on the property’s history. What was there before the current house was built? What is the history of land care? Was the property previously farmland? Have old buildings been removed, potentially leaving lead paint or plumbing behind? See AG-439-78, Soil Facts: Minimizing Risks of Soil Contaminants in Urban Gardens, for specific design strategies.

Use the plot plan to develop an up-to-date inventory of existing built features (such as the house, power lines, septic tanks, underground utilities, exterior lighting, and roof overhangs) as well as existing plants and beds, landscape features, and hardscape locations on the site. The height, style, and exterior elements of the home, as well as the construction materials used, should be noted to help with design decisions. Measure and note on the plot plan any other structures and hardscapes that may have been added, such as patios, driveways, or sidewalks.

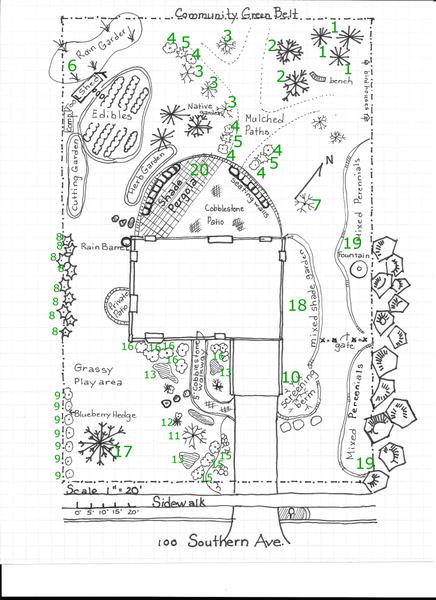

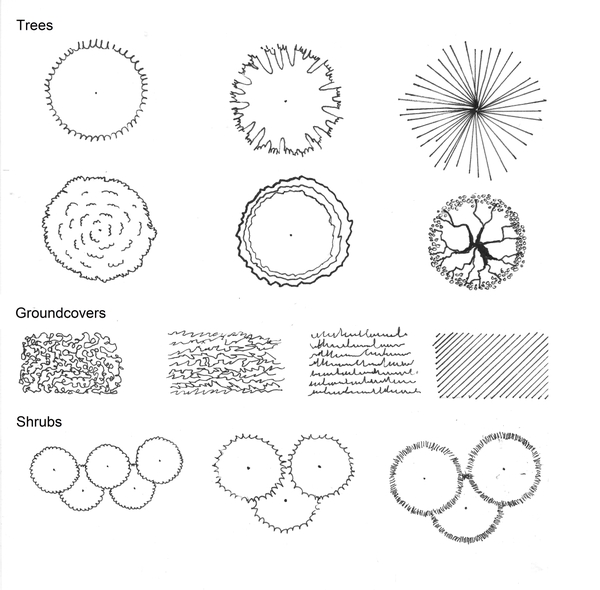

When all of the information has been gathered and marked on a rough sketch, transfer it to a final base plan. Make sure to draw to scale. Depending on the size of the property, a suitable scale, for an average homeowner landscape, is 1 inch equals 10 feet (or 1⁄10-inch scale). For a small property or courtyard a 1⁄4-inch scale may be more appropriate. Other popular landscape scales are 1:4, 1:5, 1:8, 1:10, 1:16 and 1:20. Scales of 1:4, 1:8 or 1:16 match the common increments used on a conventional ruler, but scales of 1:10 and 1:20 are used by engineers and landscape architects. Suggested symbols are shown in Figure 19–28. Be sure to indicate a north arrow on the plan. Locate any existing features on the property and the house, and be sure to include the following items:

- Aboveground and underground utilities (see “Locating Utilities” below.)

- Windows, doors, and other openings, including height off the ground

- Existing healthy, meaningful vegetation that makes an impact (to accurately note the location, use a triangulation method. See sidebar.)

- Other vegetation that may be moved to a different location (eyeball this vegetation, but do not bother to triangulate.)

- Utility meters, drainpipes, water spigots, outlets, septic tank

- Features on or near the property line

- Anything else prominent on the existing site

Mark these features on the base plan as shown in Figure 19–29.

Triangulation

Triangulation helps accurately determine the location of existing trees and shrubs on the property so they can be marked on the base plan. To triangulate, use two known fixed points. Corners of a house or other structures, walkway corners, or mailboxes are good places to start. Measure to the center of the plant from these two locations and make note of the distances. Use a scale to transfer these plant centers to the base plan.

Locating Utilities

Call 811, a free utilities location service, before you complete the base plan and 48 hours before digging is scheduled (Figure 19–30). This service notifies the electrical, phone, gas, water, and sewer utilities to come and mark the property. A different color spray paint is used for each utility. Generally, the utility line is located underground in a 5-foot zone around the marked line, 2.5 feet on either side of the line. These areas should be considered “no digging zones.” Utilities should be marked when the base plan is being developed as some design decisions may be based on where lines run. The service must return and mark again before landscape installation if the lines have faded. Figure 19–31 is an example of what can happen when utility lines and right-of-ways are ignored by a gardener.

Tips for Drawing on a Base Plan

- Have adequate paper to write on. Or better yet, make several enlarged copies of the plot plan to draw on and record measurements.

- Enlist the help of a partner. Having two people hold and read a measuring tape is much easier.

- Use a long measuring tape or invest in an inexpensive measuring wheel if the property is large. Piecing together measurements because the tape is too short can lead to errors. A 100- to 200-foot tape measures most things in an average yard.

- Record measurements carefully and legibly to avoid having to re-measure.

Inventorying the property and recording existing structures and features of the landscape also provides an opportunity to identify the positive and negative aspects of the existing landscape. One goal of effective landscaping is to create a definite relationship between the house and its environment. Note plants that should be retained and worked into the new landscape or planting. Some trees and shrubs may simply require pruning, while others may need to be relocated or removed entirely. Any neighborhood association guidelines and restrictions need to be considered. After locating the existing plants and beds on the plot plan, identify individual plants. A detailed evaluation of the negative and positive aspects of the existing landscape includes the following considerations.

Consider the house and existing hardscape:

- What is the architectural style or character?

- Is this new or established construction?

- Is it one story or two (or more)?

- Is it rustic or formal, modern, or traditional?

- What are the construction materials? What color?

- Are there walkways, walls, fences, patios, and decks that are improperly sized, in the wrong location, or in disrepair?

Consider the views:

- What are the views both within and beyond your property line?

- Where are the locations from which the landscape is viewed from inside and outside the home? Examples include views through a kitchen or sitting room window or from an existing porch or the street.

- Are the current views pleasing, or would additional plantings or hardscape add more interest to that area?

- Do any views need screening?

Consider plant density:

- Are there "overplanted" beds or areas that should be thinned?

- Are there sparse areas that would benefit from the addition of plants?

- Are there random individual or small groups of plants scattered incoherently across the site?

- Is there too much lawn or not enough?

Consider mature size of existing plants:

- Are there plants that are or will become oversized, creating a hazard or high maintenance?

- Are there undersized plants that look lost or out of scale and need to be moved or combined in a mass for better visibility?

Consider environmental benefit of existing plants:

- Do the plants properly address the impact of sunlight on summer cooling and winter heating for the residence?

- Are there any long-lived, native woody ornamental species, like willow oak (Quercus phellos), red maple (Acer rubrum), or bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), which are desirable and should be preserved?

- Do the existing plants offer a biodiversity of species that benefits the local ecosystem?

- Are any of the existing plants invasive species like privet (Ligustrum sinense or L. japonica), Japanese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda), Chinese wisteria (W. sinensis), or English ivy (Hedera helix) that should be removed?

Consider health of plants:

- Do plants require minimal pruning, spraying, and fertilizing?

- Are plants placed in ideal growing conditions—proper light conditions, soil type, and drainage?

- Are plants showing signs of disease, chronic insect depredation, or environmental stress such as poor or stunted growth, foliage discoloration, or dieback?

- Are the plants sited so that they do not compete for nutrients, water, and air circulation, which results in plant stress and disease?

- Do any plants always seem to have one problem or another throughout the year, making them candidates for removal?

Consider the landscape in the evening:

- Are there dark areas that could benefit from exterior lighting?

- Would evening-blooming plants that have white blossoms or attract nighttime pollinators add interest to the yard?

Consider design contributions of existing plant material:

- Do existing plant forms, textures, and colors contribute to coherent, unified design?

- Do existing plants offer seasonal interest?

Figure 19–28. Any symbols can be used on a plot plan. These are some options.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Step 2: Conduct Site Survey to Identify Environmental Factors

Understanding the environmental factors that exist on a site is critical to designing a functional, healthy landscape. By accurately incorporating knowledge of site-specific environmental considerations into the design. we can create a landscape that is easier to install and maintain and is more ecologically friendly. The site needs to be carefully studied for more than one season. The environmental features, including sun and wind exposures, sight lines, sound transmission, soil conditions, water flow and drainage issues, and existing landscape, must be analyzed. The results can be noted on an overlay created by taping a sheet of tracing paper over the plot plan.

Sun and Shade

The way the sun affects the house and site at different seasons greatly influences the overall design. Good plant placement is based on knowing the sun’s direction at different times throughout the day as well as at different times of the year. The yard needs to be observed throughout the day to determine which areas receive full sun (more than six hours a day), partial sun, and primarily shade. Understanding sun exposure helps us make design decisions like planting trees to provide shade to a patio in the summer or recognizing that putting a vegetable garden in an area that receives only partial sun results in little fruit when it comes time to harvest. Assessing winter and summer sun angles, as shown in Figure 19–32, tells us where to leave open areas that allow the winter sun's rays to heat the house and outdoor living areas.

Wind

Knowing the direction of prevailing winter winds is crucial for deciding where to locate a windbreak, which can be especially important in the mountains or on the coast. Understanding wind patterns is also important to refrain from including structures or plants in the design that block summer breezes from outdoor living spaces. Mark the source and direction of winds on the plan overlay to visualize where a protective wind screen should be added or where breezes should be allowed to enter the landscape unimpeded.

Sights and Sounds

Walk the property to note what is visible in various directions. Standing on the front step, is the view pleasant? What is the view from the deck in the backyard? Also note the source of any objectionable noise on the site analysis overlay. Think, too, about the views from inside the home and looking out into the yard. On the site analysis overlay, identify views on which attention should be focused, as well as those that should be screened.

Soils

The native soils in North Carolina vary from light sand to heavy clay. In addition, many families are confronted with the difficult task of landscaping in "urban soils" that may include mortar, bricks, sheetrock, plywood, plastic, and other leftovers from construction. Often during the construction of a home, the top layer of soil is removed, leaving compacted subsoils mixed with construction debris that are unsuitable for plant growth. Have the soil tested, and on the site plan make note of both the soil type and the topsoil depth. Evaluate the soil in several sections of the property as soil types can change over a short distance, particularly if there is a change in elevation.

Water

Review a topographical map of the site and walk the property to examine stormwater patterns. Look for evidence of erosion and note any poorly drained or low areas that remain wet for several days after a rain. For the areas with evidence of erosion, examine rainwater harvesting options to reduce the amount of water flowing through these areas after a rain event. Use cisterns or rain barrels to harvest roof runoff and store it for later use (Figure 19–33). Consider contouring slopes to slow the runoff, minimize erosion and provide time for water to soak into the soil. Design options for addressing low-lying areas include installing an underground drainage system, building raised beds, grading, or planting a rain garden.

Overall, by addressing these environmental factors, we can create a design that is in harmony rather than in conflict with the observed natural patterns. This strategy leads to a successful, attractive, low maintenance, and ecologically beneficial landscape.

Figure 19–33. A rain barrel is filled with a PVC pipe attached to a roof downspout. This barrel is close to the garden for easy access to water vegetables.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

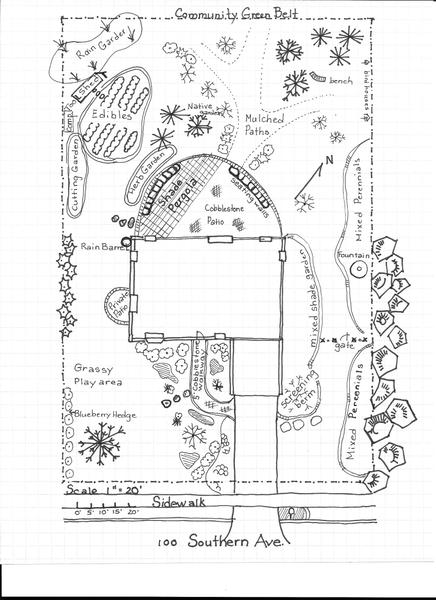

Step 3: Identify Activities and Uses for Landscape

To design a landscape that is aesthetically pleasing, enjoyable, and functional, we need information from the people who will use the space. What are their personal needs and wants, what functions do they want the space to fulfill? What activities will occur regularly in the future landscape? Checklist 19–1 is a printable list of possible uses and activities to consider when planning a landscape. Ultimately, the activities identified for a given landscape provide direction toward a design that suits all the users.

Planning Enough Space for a Deck or Patio

A landscape wish list may be long. Adequate space to comfortably incorporate the items on the list is essential. In the case of decks and patios, it is better to go too large rather than too small. A deck or patio for outdoor entertaining should comfortably accommodate the maximum number of guests who will be using the space. Wall seating around the edge of a patio and built-in benches for a deck take advantage of space and limit the need for extra furniture (Figure 19–34). Measure outdoor furniture planned for the space and allow 2 to 3 feet of walking room around chairs. Using the plot plan scale, cut out paper patio furniture pieces sized to scale. Place and move pieces on the plot plan to help find an ideal location. People are accustomed to more elbowroom outside. Stake off the space to see if it is the right size, if the planned location takes advantage of good viewpoints in the yard and beyond, and if the site is out of direct traffic patterns to and from the house.

Figure 19–34. This small patio area extends its seating options by providing a flat topped wall.

Field Outdoor Spaces, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Step 4: Locate and Develop Use Areas

A residential landscape consists of areas that are used for different purposes. In this step, we divide the site into several separate areas—each serving a purpose, but all combining into the overall design.

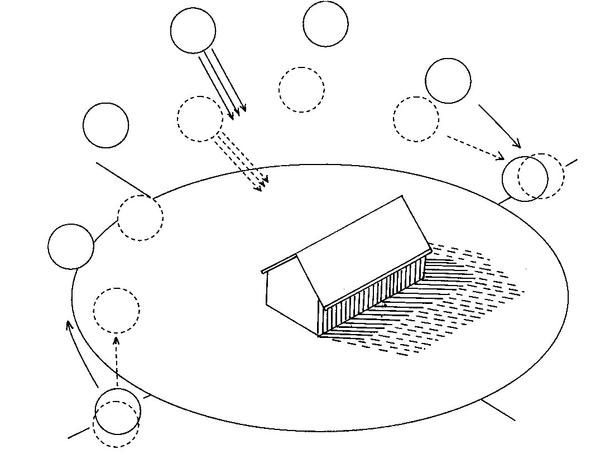

In residential landscapes, three general areas—public, private (family), and service (utility)—are used to organize activities and uses. Each area is developed to meet the user’s needs and priorities (Checklist 19–2). After categorizing the activities, we can locate these areas for various uses on the plot plan. Try to provide enough space for each activity within a given use area. Using another overlay sheet of tracing paper taped over the plot plan, note these use areas. Drawing bubbles to indicate use areas on the overlay helps to loosely define spaces for each activity (Figure 19–35).

The public use area is usually in the front of the house. The private use or family area is often in the back of the house. And the service area is generally in the backyard or side yard. It is important to locate and then develop each area so that it meets user needs, contributes to an attractive overall landscape, and addresses environmental factors identified in Step Two.

Public Use-Entrance Areas and Front Yards

The public use area is most often seen by passersby and guests and usually includes the front yard, drive, walks, and main entrance to the home. A first consideration is to direct visitors to the front door. This can be accomplished with several landscape features.

First, consider the front walk. This walk should be comfortable for two people walking side by side—a minimum of 41⁄2 feet is recommended. The front entrance can be enhanced by a walkway with an interesting surface texture, such as brick, slate, concrete pavers, aggregate, or stained concrete (Figure 19–36).

Outdoor lighting improves safety and directs pedestrian traffic to the entrance after dark. Low, indirect lighting can safely light paths. Municipalities and other government agencies are moving toward decreasing light pollution. For these reasons, incorporate appropriate light schemes into the landscape, including down-lighting of specimen plantings and hardscape. Another environmentally sustainable solution is solar lighting.

To help guide visitors to an entrance area add a focal point—for example, an interesting tree with ground cover underneath or a planter with a specimen shrub. Trees, shrubs, and grass can be used to focus attention on the entryway. Hardscape elements, including rocks, planters, trellises, arbors, and water features can also draw focus to the entryway.

Vehicle parking needs to be considered. If off-street parking is needed to accommodate visitors’ cars, consider locating these spaces where they are easily accessible to the front entrance. Allow enough room for a door to swing open and a surface where someone exiting a vehicle can stand.

When planning the foundation areas, consider the mature size, color, texture, and number of plants needed. Consider the individual character of a plant so that as it matures it grows without major maintenance. Modern house foundations are often attractive and do not need to be hidden by dense borders of plant material.

If trees are desired near the house structure, choose a tree with a small canopy when fully grown so the branches do not interfere with the porch or roof. Placing tall trees in the backyard, and medium or small ones on the sides and in front, highlights the house (Figure 19–37). Examples of small canopy trees are dogwood (Cornus florida), Japanese flowering apricot (Prunus mume), Japanese maple (Acer palmatum), eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), and serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.). Tree-form evergreen shrubs are also useful, such as yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria), camellia (Camellia japonica), inkberry holly (Ilex glabra), or wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera). When selecting trees or shrubs to frame a front entry, consider each plant’s texture, color, shape, and size at maturity. The goal is to enhance the total visual effect while not blocking doors or windows or creating future maintenance issues from either plant root systems or branches and foliage.

While a front lawn is a very common feature, consider reducing the amount of area planted with turfgrass. Unless there are designated uses for a turf area in the front yard, the costs, labor, and chemical inputs often involved in maintaining a lawn can be avoided by planning a turf-free front landscape. Incorporate masses of ground covers or mulched areas in the front landscape to create interesting lines. A front yard without a lawn can be beautiful and inviting, more easily maintained than a lawn, and contribute to a sustainable, environmentally friendly landscape (Figure 19–38).

Private Use—Family Activity Areas

When designing areas to be used privately by the family, refer back to the needs identified in Step 3. With North Carolina’s pleasant climate, outdoor activities can be enjoyed most of the year, so decks, patios, and terraces should be considered an integral part of the residential landscape. The outdoor living areas should be easily accessible to the indoor living and kitchen areas of the home and should include private areas with attractive views.

Hot tubs, swimming pools, plant containers, raised beds for edibles, flower and woody ornamental gardens, water features, and sculptures are features that enhance an outdoor living area. Be sure to include space for recreation and sports. Some families enjoy basketball, tennis, or swimming, which requires special planning. If adding a large recreational feature like a tennis court or a swimming pool is not affordable with the initial landscape installation but is desired for the future, be sure to leave enough space in the private use area.

Consider children's needs for landscape space (Figure 19–39). Sandboxes, swing sets, playhouses, and toys should be located in the family activity area. Consider how children’s needs and the use of that space will transition as the children grow up. Because play spaces are generally placed in major sight lines from the house, they are ideal for future focal points, such as a water feature or specimen plant.

Utility or Service Use Areas and Side Yards

Every residential landscape requires an area where gardening equipment, garbage cans, firewood, bicycles, and other items can be stored. Often these items end up at one side of the garage, behind the back porch, or under the deck. Set aside a certain amount of space for these necessities. Try to provide space for an outside utility building that is easily accessible (Figure 19–40).

Remember to keep the back of the site accessible to vehicles. Access facilitates major landscape maintenance tasks (like tree removal) or the addition of new landscape features, such as a concrete patio or a swimming pool.

If desired, spaces for gardening such as a greenhouse, beds for vegetables, or a compost pile can be provided in this area. As noted above, however, edibles can be integrated into the private use areas. If unsightly utility areas are visible from the house or patio, a screening wall or hedge may be needed (Figure 19–41). Do not forget to screen off unsightly areas from the neighbors.

A side yard is often the location for house utilities, including electricity and natural gas meters, cable access, or air-conditioning units. Homeowners do not typically spend a lot of money on their side yards because they do not spend a lot of time there. These utilitarian spaces can still be incorporated into the overall landscape at little cost by using attractive, functional access paths and screening materials. Be sure to keep plants and any screening structures away from utilities, both for ease of maintenance and to ensure good air flow.

Figure 19–36. The arbor and low growing heather are inviting features leading visitors directly to the front door on this flagstone walkway.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Figure 19–37. This Japanese maple with a modest canopy is the right scale for this small front yard.

Lara604, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Figure 19–38. No one misses the lawn in this inviting front yard that incorporates a stone path, shrubs, perennials, and ground covers.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Figure 19–39. These children are enjoying a natural play space made from tree rounds.

Lucy Bradley CC BY 2.0

Figure 19–40. A garden shed can be attractive as well as functional. It is the ideal place to store garden tools and potting supplies but it can also become a feature in the landscape as seen here with the cut-end logs decorating the walls.

Henry Burrows (foilman), Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 19–41. This lattice is masking a power utility box with Italian Clematis (Clematis viticella) and Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) vines. These are deciduous vines that are easy to prune back, maintaining access around the box.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Step 5: Design

Once the site has been analyzed, the activity wish list made, and bubble diagrams drawn (Figure 19–35) to best locate the activities and elements, the landscape layout can be determined. A landscape can be informal, formal, or a combination of the two. Informal landscapes tend to have curvilinear lines and winding paths. Formal landscapes have more formal planting beds and pathways with rectilinear lines.

A combination landscape might have a formal layout, but informal, loose plantings within the framework. Selecting the overall landscape layout is critical because it helps set the mood and energy of the space. It is important to get the layout right the first time as it can be time consuming and expensive to start over. The overall goal of this step is to get all the pieces of design to fit together like a puzzle so the final landscape, even after multiple installation phases, appears to be a unified, well-thought-out design.

Landscaping guided by a series of arbitrary "rules" such as "always plant shrubs in groups of three or five" and "never plant annuals in the public area" does not consider the needs of individual families and sites. Such landscaping rarely results in good design. Good design does not have to be limited by such so-called rules. Our objective in designing a landscape is not only creating good visual relationships. A successful landscape provides meaningful and useful spaces for people and their animals that fit with a family’s desired aesthetic preferences. And a successful landscape promotes environmental stewardship. Developing a landscape design requires an understanding of the dynamic nature of the landscape. When we create a final design plan, we rely on basic design considerations, environmental design considerations, plant selection guidelines, and plan preparation instructions.

Basic Design Considerations

Emphasize by Grouping Plants

Rhododendrons, azaleas, dogwoods, or other woody ornamentals and herbaceous perennials can be mass-planted in informal beds (Figure 19–42). Try to locate the plants so that a natural scene develops as they mature. Plant the shrubs or trees together in one large bed and mulch well. Planting woody perennials en masse also provides winter structure for the landscape. Consider adding bulbs or borders that have masses of herbaceous perennials or annuals for seasonal color.

Provide Privacy

If the site analysis reflects a need to screen unsightly views, provide a noise barrier, or create privacy, plant evergreen shrubs or build a fence (Figure 19–43). If room and time allow, a natural evergreen hedge is a good screening option. Vines on trellises create effective screens in tight spaces. Many trees, shrubs, and vines that make good screens grow very well in North Carolina. Although deciduous plants lose their leaves in the fall, investigate their stem size and arrangement because a densely branched deciduous shrub can work as an effective and interesting screen even after its leaves have dropped.

Specimen Plants

In selecting specimen plants, consider quality—not quantity. By definition, specimen plants are plants grown alone for ornamental effect, rather than being massed with other plants as are bedding plants or edging plants (Figure 19–44). Specimen plants are located in the design to create focal points and draw attention to a specific area.

Succession

We must design for time, or succession, when dealing with living, growing plant material. The initial planting should be based on the mature size of the plants. Although the entire space will not be filled, young, new plants should be placed so they will have space to grow and attain their mature size. Plan for the in-between areas in the newly planted garden so these open areas do not become weed-filled. One option is regular mulching with an organic material, such as pine fines, shredded leaves, or double-hammered hardwood mulch. All of these mulches suppress weeds, look attractive, conserve moisture, and protect and build healthy soil. Gaps can also be filled temporarily with annuals for a few years as long as they do not overcrowd or compete with permanent plantings.

Do not overcrowd plants during initial planting to create an “instant landscape” (Figure 19–45). Planting twice as many as needed, thinking they will be thinned out in a few years, doubles the cost of the job, and often the thinning never happens. Plants become overcrowded and compete for water and nutrients. Stressed, overcrowded plants are more susceptible to depredation by insects and plant diseases. Pests lead to unattractive, maintenance-intense plants that eventually need to be removed because they are unhealthy.

Ecologically Based Design Considerations

Residential landscapes are part of a larger landscape and ecological community. When we design an environmentally friendly landscape, we protect the site’s natural elements and treat the landscape as a living system. We consider reducing energy, water, and material inputs, and avoid the use of toxic or prohibited materials. The following environmentally friendly design techniques and considerations are based on valuing ecosystem services in the landscape.

Designing for Water Conservation

Traditional landscape designs often incorporate the removal of all water offsite as quickly as possible. In an ecologically based design, water is not treated as a waste product to be captured and conveyed offsite. Instead, we view water as a resource to be captured and used in the landscape. The idea is to balance water inputs from precipitation, surface flow, and piped-in sources with outputs from evapotranspiration, runoff, and water that infiltrates into the soil. This balance helps prevent negative environmental effects such as erosion and surface and groundwater pollution. We rely on the following design techniques and concepts to achieve water conservation and balance:

- Hardscapes create a slight slope on driveways and sidewalks to allow water to flow into the landscape rather than being diverted to the stormwater system. Where possible, use permeable surfaces for sidewalks, patios, and driveways (Figure 19–46) to allow water to soak into the ground.

- Earthworks such as earthen berms and swales are used to contour the land to slow and capture rainwater, allowing it to infiltrate the soil. A swale is a trench dug perpendicular to the slope of the land. They are most effective on gentle slopes of less than 30 degrees. Begin installing swales as high in the landscape as possible, capturing water before it builds momentum and causes erosion. Continue building swales down the slope to promote infiltration and minimize stormwater runoff. A berm is a mound of soil that holds water in a plant’s root zone. Terracing can also slow down water movement (Figure 19–47).

- Rain gardens are designed to capture and infiltrate rainwater into the landscape (Figure 19–48). Select a location in full or partial sun that is at least 2 feet above the water table. The site should also be between the source of stormwater runoff (roofs and hardscapes) and where the water leaves the property. Do not place the rain garden within 10 feet of the house foundation or within 25 feet of a wellhead or a septic system drain field. Avoid underground utilities. Use “Sizing Your Rain Garden,” a sizing chart, to calculate the size of water garden needed to manage a site’s stormwater. Dig a hole 4 to 6 inches deep with a slight depression in the center. Use the soil removed from the hole to create a berm along the side of the rain garden opposite the side into which the water flows. Cover the berm with mulch or grass to prevent erosion. Create a filter bed by slightly recessing the garden and adding compost to whatever soil is already on site. Compost works well with all soil types, adding valuable nutrients and microbes. In sandy soils it slows infiltration rates, and in clay soils it improves infiltration and pore space. Do not add sand to a filter bed as it can cause clay soils to become brick-like. Install plants that can withstand both short periods of standing water and periods of drought. Then cover with 2 to 3 inches of hardwood mulch.

- Green roofs or a living roof are partially or completely covered with vegetation and some type of growing medium, planted over a waterproof membrane. It may also include additional layers such as a root barrier and drainage and irrigation systems. Green roofs yield several important environmental benefits, including reducing stormwater runoff, restoring the natural water cycle in urban settings, enhancing biodiversity, and lowering outside building temperatures (Figure 19–49). In addition, green roofs increase awareness of stormwater management issues.

- Rain barrels and cisterns are containers placed under downspouts to capture and store rainwater until it is needed for landscape irrigation. These containers prevent uncontrolled runoff. They can also be used to collect condensate from air conditioners, allowing the water to be used as needed for landscape irrigation and conserving water, energy, and money. This reliable, high-quality source of water is available during summer months when irrigation needs are highest. In the best-case scenario, rain barrels can be used in concert with rain gardens, directing any runoff from barrels to a rain garden.

- Gray water is water discharged from bathtubs, showers, wash basins (except the kitchen sink), dishwashers, and clothes washers. Using gray water saves money by reducing the amount of tap water purchased for use in the garden and landscape as well as the energy that would have been used to treat and transport tap water. Using gray water also saves the energy that would have been used to transport and treat the gray water if it had entered the wastewater treatment system. A person who lives in a newer home with water efficient fixtures generates approximately 35 gallons of gray water per day (12,320 gallons per year), while a person in an older home generates approximately 46 gallons per day (16,192 gallons per year). To protect groundwater and public health, rely on these requirements for safe use of gray water:

- The water must be used on the residential property where it was discharged. It must not be allowed to run off onto adjoining property, roadways, or into ditches or storm drains.

- The water must be applied to the landscape as soon as practical (within 24 hours of production).

- Apply the water directly to the ground. Do not spray it.

- Do not use gray water when laundering diapers, dying clothes, or when using any detergents, solvents, or other products that might be hazardous to the environment.

- Do not use gray water if any resident of the house has an infectious disease, such as diarrhea or hepatitis, or if any resident has internal parasites.

- Do not drink or apply gray water to edible crops (except those with a heavy rind like citrus and nuts).

- Include the capacity to divert gray water to the sewer system when desired.

- Check current state laws, local ordinances, and homeowner association covenants and restrictions prior to installing a gray water system.

1,000 square foot roof produces 630 gallons of runoff in a 1-inch rainstorm.

Other recommended design practices for water conservation include:

- Group plants according to water needs, such as “high water use” or “no supplemental water.”

- Reduce the size of the lawn. As much as half of all the water used outdoors by the average homeowner goes to lawn irrigation.

- Install a multi-zone irrigation system with a rain sensor or soil moisture monitor.

- Avoid watering buildings, driveways, streets, and sidewalks.

Applying good design practices to conserve water in the landscape also conserves the energy that would have been required to provide that water.

Designing for Energy Conservation

Landscape plants provide shade (protection from radiant heat), minimize air movement (insulation), and cool the air through transpiration (release of water from leaves which then evaporates, a process that consumes energy and results in heat reduction).

The passive energy-conserving impact of a plant species depends on its size, whether it is deciduous or evergreen, the shape of its canopy, and the density of its foliage. Trees, shrubs, and vines are all effective, although arbors or trellises have to be included for vines or to espalier shrubs and trees.

Locate deciduous trees where the greatest benefit is derived from summer shade and winter sun—on the western side to protect the home from noon to sunset. There is also some benefit to planting on the eastern side to protect from sunrise to noon. Shade not only structures but also outdoor seating areas, walls, and hardscapes. Pay particular attention to shading windows, which are most vulnerable to heat gain. Shading air conditioners can reduce the air temperature inside the home, but be sure to allow for adequate air flow around the unit. Use trees to shade the walls rather than the roof of the house. Tree limbs over the roof shed litter that clogs rain gutters. If heavy limbs fall during a storm, they can damage the house.

Create a windbreak by identifying the prevailing winter wind and installing evergreen trees upwind from the house. One row of trees is effective, but a windbreak of up to five rows that includes several different species is more effective. The windbreak also serves as a privacy screen. A biodiverse windbreak (or screen) consisting of native plants also provides sources of food and shelter for beneficial insects and wildlife, including birds.

Do not over-plant! Too many trees and shrubs near the house can cause moisture problems that lead to mildew, mold, and high humidity. The wind and the sun should periodically dry the area around the home. Over-shading a home may result in higher energy and maintenance bills because lights have to be used more often and an air conditioner may be needed to control humidity.

Carefully positioned trees, shrubs, and vines can save up to 25% of a typical household’s energy consumption for cooling and heating. Combining these landscape ideas with proper insulation and conservation habits should produce a significant decrease in energy consumption.

Designing for Wildlife Conservation

Landscapes are ecosystems. Ecosystems require a diversity of plants in various layers or levels to provide adequate habitat for wildlife. Consider including a water feature with shallow edges to provide drinking and bathing water for wildlife. Selecting native plants helps to attract birds, pollinators, and beneficial insects to the yard. See chapter 20, "Wildlife," for specific tips on attracting and managing wildlife in the landscape.

Designing for Food Security

Incorporating edibles into the entire landscape instead of only in a vegetable garden is a way to make the landscape more eco-friendly. Doing so also makes more efficient use of space by incorporating plants that perform multiple functions (add beauty to the garden, provide food and cut flowers, and attract pollinators). It is not necessary to substitute edible plants for all ornamentals, but many edible woody landscape plants have high ornamental value. The goal is to progress from the typical backyard vegetable garden and develop a plan that uses edible plants to solve functional landscape problems. Plan for year-round harvest by selecting a variety of plants that ripen at different times throughout the year.

Edibles are available that meet most plant selection design criteria. For trees, consider fruit and nut trees. Most deciduous fruit trees (including apple, fig, pear, cherry, peach, and plum) come in a variety of sizes ranging from a mature height of 8 feet to a mature height of 30 feet. Select one to fit the space. Be sure to provide adequate sunlight as fruit trees require 6 to 7 hours a day. For seasonal color, instead of purchasing annual flowers consider colorful vegetable plants. The bright stems of rainbow chard spruce up any planting bed. Kale comes in many varieties that have interesting colors and textures (Figure 19–50).

Instead of planting ornamental ground covers, think about planting strawberries or evergreen raspberries. An area with well-drained soil that receives at least 6 to 7 hours of direct sunlight produces strawberry plants with lush green foliage, spring blossoms, and early summer fruit. Rosemary, thyme, oregano, lavender, and many other herbs offer a variety of design options. Some are evergreen, some are shrublike, some create creeping ground covers, and all have colorful blooms and unique fragrances.

Blueberry bushes are a good substitute for a privet (Ligustrum sp.) or hedges of Asian hollies (for example, Ilex cornuta ‘Burfordii’). Rabbiteye cultivars are more widely adapted to different soils than highbush cultivars. Rabbiteye blueberries do not tolerate the cold climate of the mountains but grow well in full sun all across the NC piedmont and coastal plain. Acid soil (with a pH of 4.5 to 5.5) usually promotes the best growth. Include two or more cultivars in the design to ensure proper pollination. Read more in chapter 14, “Small Fruits.”

Designing to Minimize Maintenance

To make the landscape more efficient and less frustrating to maintain, consider these design suggestions:

- Avoid sharp angles, tight corners, narrow lawns, and irregular edges that are hard to mow and water.

- Reduce turfgrass areas—lawn is labor- and material-intensive, requiring regular mowing and other maintenance tasks plus irrigation, fertilizer, and other chemicals.

- Choose plants whose growth habit and mature size meet the design requirements to minimize pruning and shearing to maintain the desired size and shape.

- Look for plants that are drought-tolerant, wind-resistant, and adapted to low fertilization to save on maintenance.

- Group plants with the same water needs together to save time and money on irrigation.

- Locate the compost bin near where the green waste is generated.

- Consider minimizing the removal of organic material from the landscape in the design. Practice the law of return. For example, leave grass clippings on the lawn to enrich and protect soil, which feeds the grass, saves the labor of collecting and bagging clippings, and conserves the energy expended to truck them away. Plant deciduous trees and shrubs in large beds where leaves can accumulate and biodegrade to enrich and protect soil. This practice also conserves water, labor, and energy.

Designing for Wildfire Resistance

If wildfire is a potential problem, create at least a 30-foot defensible space around the house (more if the house is on a slope or if the surrounding vegetation is particularly flammable) by removing flammable material from the area surrounding the building. Identify the prevailing wind, which is the direction from which the fire is most likely to approach. Be sure not to design storage for firewood, building materials, or other flammable landscape materials on that side of the yard. Remove any dead vegetation within the defensible space. Eliminate fuel ladders, plants of varying heights located near each other, which provide a means for the fire to jump to the canopy. Leave open space between plants or groups of plants within the defensible space. Do not plant within 5 feet of any structure or use dense masses of plants.

To learn more about Permaculture, another ecologically based approach to landscape design see Appendix G.

Plant Selection

Plants are the dynamic heart of a landscape, and thoughtful plant selection is essential to developing a beautiful, earth-friendly landscape. Proper plant selection and placement create an appealing landscape, improve property value, beautify the community, and build a healthy local ecosystem. Selecting the right plant for the right place reduces the need for irrigation water, fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides, and labor.

Plants can be selected for their aesthetic or ecological value to fulfill specific functions such as screening or noise control. Plants are incorporated into the design to fill several visual and sensory roles in the landscape. Plants form a structural framework for the garden and yard, establish horizontal and vertical diversity and transition, and provide focal points. They can be used for screening and creating seasonal impact with foliage, bloom, twig color, or trunk architecture. Many plants add fragrance to the environment. Selections based on ecological value can reduce lawn area, control erosion, and add biodiversity by attracting, hosting, and feeding pollinators, beneficial insects, and other wildlife—including birds.

Native plants or cultivars of native species benefit the local ecosystem in a myriad of ways including by supporting insects, the primary food source for nesting birds and other native fauna. In addition, they attract native pollinators, including birds, bats, butterflies, bees, and moths as well as providing preferred food, shelter and habitat for wildlife. Native plants also enhance the beauty of all types of gardens—from formal to informal designs—and provide a sense of place and regional history. An extensive variety of native plants occur in North Carolina and they can be used to incorporate elements of local natural systems. See chapter 12, "Native Plants" for more information. There are also a variety of non-native ornamental species that thrive in North Carolina. When selecting non-natives make sure they are well adapted to the site’s growing conditions but are not designated as weedy or invasive or considered a threat to natural habitats.

Avoid invasive plants such as English ivy (Hedera helix), privet (Japanese and Chinese Ligustrum spp.), Japanese and Chinese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda and W. sinensis), and Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), all of which are detrimental to the local landscape and environment, including undeveloped natural areas. For lists of invasive plants, see the NC Invasive Plant Council, Going Native: Urban Landscaping for Wildlife with Native Plants, or the NC Native Plants Society.

To put the right plant in the right place, we must understand each plant’s environmental requirements and its design characteristics. For example, choose drought-resistant or low-moisture plants for a location with limited available water. Or select a mounding, low-growing broadleaf evergreen for a low hedge next to a walkway.

Environmental requirements of the plant to consider include:

- Moisture needs

- Light exposure:

- Full sun: at least 6 full hours of direct sunlight

- Part sun/part shade: terms often used interchangeably to mean 3 to 6 hours of sun each day, preferably in morning and/or early afternoon

- Full shade: less than 3 hours of direct sunlight each day with filtered sunlight during rest of day

- Insect and disease resistance

- Heat and wind tolerance

- Soil type preference